Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EXCEL - IDEA: XBRL DOCUMENT - Kite Pharma, Inc. | Financial_Report.xls |

| EX-31.2 - EX-31.2 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex312_20141231259.htm |

| EX-32.2 - EX-32.2 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex322_20141231261.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EX-31.1 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex311_20141231258.htm |

| EX-23.2 - EX-23.2 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex232_20141231686.htm |

| EX-23.1 - EX-23.1 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex231_20141231257.htm |

| EX-10.23 - EX-10.23 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex1023_20141231265.htm |

| EX-10.22 - EX-10.22 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex1022_20141231312.htm |

| EX-32.1 - EX-32.1 - Kite Pharma, Inc. | kite-ex321_20141231260.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, DC 20549

FORM 10-K

(Mark One)

|

x |

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014

OR

|

¨ |

TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the transition period from to

Commission File Number: 001-36508

KITE PHARMA, INC.

(Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter)

|

Delaware |

|

27-1524986 |

|

(State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) |

|

(IRS Employer Identification No.) |

|

|

|

|

|

2225 Colorado Avenue Santa Monica, California |

|

90404 |

|

(Address of Principal Executive Offices) |

|

(Zip Code) |

(310) 824-9999

(Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code)

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

|

|

|

|

|

Title of each class |

|

Name of each exchange on which registered |

|

Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share |

|

The NASDAQ Global Select Market |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K (§ 229.405 of this chapter) is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. x

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, or a smaller reporting company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer”, “accelerated filer” and “smaller reporting company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

|

Large accelerated filer |

|

¨ |

|

Accelerated filer |

|

¨ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-accelerated filer |

|

x (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) |

|

Smaller reporting company |

|

¨ |

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). Yes ¨ No x

The aggregate market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates of the registrant based on the closing price of the registrant’s common stock as reported on The NASDAQ Global Select Market on June 30, 2014, the last business day of the registrant’s most recently completed second quarter, was $696.0 million.

As of March 23, 2015, there were 42,520,601 shares of the registrant’s common stock, par value $0.001 per share, outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s definitive Proxy Statement relating to its 2015 Annual Meeting of Stockholders are incorporated by reference into Part III of this Annual Report on Form 10-K where indicated. Such Proxy Statement will be filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission within 120 days after the end of the fiscal year to which this report relates.

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

Page |

|

|

|

|||

|

Item 1. |

|

|

4 |

|

|

Item 1A. |

|

|

32 |

|

|

Item 1B. |

|

|

59 |

|

|

Item 2. |

|

|

59 |

|

|

Item 3. |

|

|

59 |

|

|

Item 4. |

|

|

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Item 5. |

|

|

60 |

|

|

Item 6. |

|

|

62 |

|

|

Item 7. |

|

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations |

|

63 |

|

Item 7A. |

|

|

69 |

|

|

Item 8. |

|

|

70 |

|

|

Item 9. |

|

Changes in and Disagreements with Accountants on Accounting and Financial Disclosure |

|

97 |

|

Item 9A. |

|

|

97 |

|

|

Item 9B. |

|

|

97 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Item 10. |

|

|

98 |

|

|

Item 11. |

|

|

98 |

|

|

Item 12. |

|

Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters |

|

98 |

|

Item 13. |

|

Certain Relationships and Related Transactions and Director Independence |

|

98 |

|

Item 14. |

|

|

98 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

Item 15. |

|

|

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

100 |

|||

1

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This Annual Report on Form 10-K, or this Annual Report, may contain “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, or the Exchange Act, which are subject to the “safe harbor” created by those sections. Our actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in these forward-looking statements as a result of various factors, including those set forth below under Part I, Item 1A, “Risk Factors” in this Annual Report.

We may, in some cases, use words such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “should,” “will,” “would” or the negative of those terms, and similar expressions that convey uncertainty of future events or outcomes to identify these forward-looking statements. Any statements contained herein that are not statements of historical facts may be deemed to be forward-looking statements and are based upon our current expectations, beliefs, estimates and projections, and various assumptions, many of which, by their nature, are inherently uncertain and beyond our control. Forward-looking statements in this Annual Report include, but are not limited to, statements about:

|

● |

the success, cost and timing of our product development activities and clinical trials; |

|

● |

the ability and willingness of the National Cancer Institute, or the NCI, to continue research and development activities relating to our engineered autologous cell therapy, or eACT, pursuant to the Cooperative Research and Development Agreement, or CRADA, with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, as represented by the NCI; |

|

● |

our ability to obtain and maintain regulatory approval of KTE-C19 and any other product candidates, and any related restrictions, limitations and/or warnings in the label of an approved product candidate; |

|

● |

the ability to license additional intellectual property relating to a product candidate targeting the EGFRvIII antigen from a third-party and relating to additional product candidates from the National Institutes of Health and to comply with our existing license agreements; |

|

● |

our ability to obtain funding for our operations, including funding necessary to complete further development and commercialization of our product candidates; |

|

● |

the commercialization of our product candidates, if approved; |

|

● |

our plans and ability to research, develop and commercialize product candidates, including under our research collaboration with Amgen Inc.; |

|

● |

our ability to attract collaborators with development, regulatory and commercialization expertise; |

|

● |

our ability to integrate T-Cell Factory B.V., or TCF, a Dutch company we recently acquired, and our ability to potentially significantly expand our pipeline of T cell receptor based product candidates using TCF’s proprietary TCR-GENErator technology platform; |

|

● |

future agreements with third parties in connection with the commercialization of our product candidates and any other approved product; |

|

● |

the size and growth potential of the markets for our product candidates, and our ability to serve those markets; |

|

● |

the rate and degree of market acceptance of our product candidates; |

|

● |

regulatory developments in the United States and foreign countries; |

|

● |

our ability to develop our own clinical manufacturing facility and commercial manufacturing facility; |

|

● |

our ability to contract with third-party suppliers and manufacturers and their ability to perform adequately; |

|

● |

the success of competing therapies that are or may become available; |

|

● |

our ability to attract and retain key scientific or management personnel; |

|

● |

the accuracy of our estimates regarding expenses, future revenue, capital requirements and needs for additional financing; |

|

● |

our expectations regarding the period during which we qualify as an emerging growth company under the JOBS Act; |

|

● |

our ability to in-license, acquire, or invest in complementary businesses, technologies, products or assets to further expand our portfolio of eACT-based product candidates or to complement our eACT-based product candidates; |

|

● |

our use of cash and other resources; and |

|

● |

our expectations regarding our ability to obtain and maintain intellectual property protection for our product candidates. |

We caution you that the risks, uncertainties and other factors referenced above may not contain all of the risks, uncertainties and other factors that are important to you. In addition, we cannot guarantee future results, level of activity, performance or achievements. Any

2

forward-looking statement made by us in this Annual Report speaks only as of the date of this Annual Report or as of the date on which it is made. Except as required by law, we undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, after the date of this Annual Report.

Trademarks and Trade names

We have common law, unregistered trademarks for Kite Pharma and eACT based on use of the trademarks in the United States. This Annual Report contains references to our trademarks and to trademarks belonging to other entities. Solely for convenience, trademarks and trade names referred to in this Annual Report, including logos, artwork and other visual displays, may appear without the ® or TM symbols, but such references are not intended to indicate, in any way, that we will not assert, to the fullest extent under applicable law, our rights or the rights of the applicable licensor to these trademarks and trade names. We do not intend our use or display of other companies’ trade names or trademarks to imply a relationship with, or endorsement or sponsorship of us by, any other companies.

3

Overview

We are a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the development and commercialization of novel cancer immunotherapy products designed to harness the power of a patient’s own immune system to eradicate cancer cells. We do this using our engineered autologous cell therapy, or eACT, which we believe is a market-redefining approach to the treatment of cancer. eACT involves the genetic engineering of T cells to express either chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs, or T cell receptors, or TCRs. These modified T cells are designed to recognize and destroy cancer cells. We currently fund a Phase 2 clinical trial of a TCR-based therapy and multiple Phase 1-2a clinical trials of CAR- and TCR-based therapies that are each being conducted by our collaborator, the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute, or the NCI. In an ongoing clinical trial, as of November 30, 2014, patients with relapsed/refractory lymphomas and leukemias treated with CAR-based therapy experienced an objective response rate of 76%.

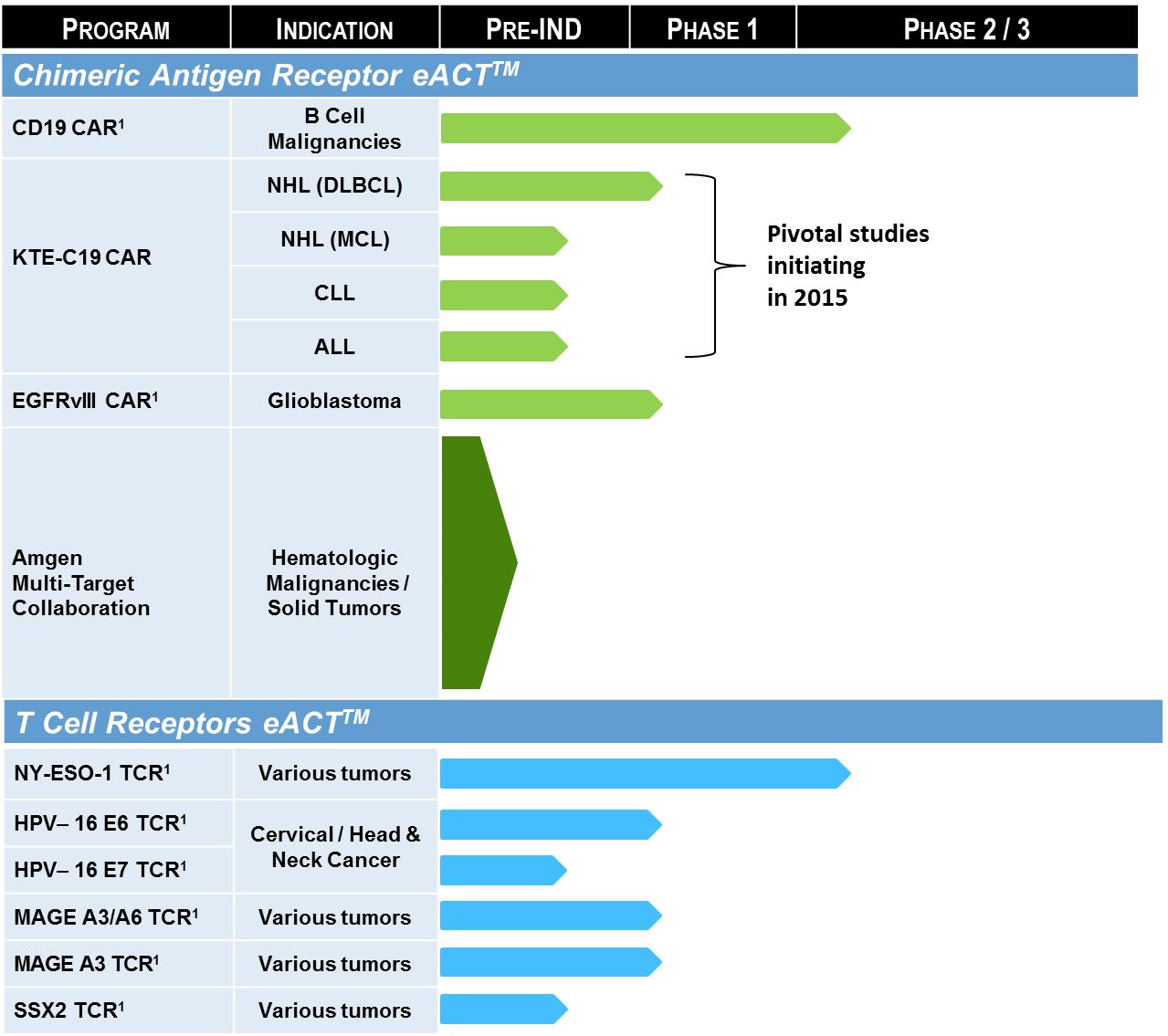

We plan to initiate a Phase 1-2 clinical trial in the first half of 2015 for our lead product candidate KTE-C19, a CAR-based therapy, in patients with refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma, or DLBCL, primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma, or PMBCL, and transformed follicular lymphoma, or TFL. DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL are types of aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or NHL. If we believe the data are compelling, we plan to discuss with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, the filing of a Biologics License Application, or BLA, for accelerated approval of KTE-C19 as a treatment for patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. In addition, we plan to begin Phase 2 clinical trials in 2015 for KTE-C19 in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma, or MCL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or CLL, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL. If we believe the data are compelling, we plan to pursue FDA approval for the additional indications.

Immuno-oncology, which utilizes a patient’s own immune system to combat cancer, is one of the most actively pursued areas of research by biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies today. Interest and excitement for immuno-oncology is driven by recent compelling efficacy data in cancers with historically bleak outcomes and the potential to achieve a cure or functional cure for some patients. We believe eACT presents a promising innovation in immunotherapy. eACT has been developed through our collaboration with the NCI, where the program is led by Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., a recognized pioneer in immuno-oncology. Our Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Arie Belldegrun, M.D., FACS, in addition to his prior roles at Agensys, Inc. and Cougar Biotechnology, Inc., also has significant experience in this field dating back to his time at the NCI as a research fellow in surgical oncology and immunotherapy with Dr. Rosenberg.

The patient’s immune system, particularly T cells, is thought to play an important role in identifying and killing cancer cells. eACT involves modifying a patient’s T cells outside the patient’s body, or ex vivo, causing the T cells to express CARs or TCRs, and then reinfusing the engineered T cells back into the patient. CARs can recognize native cancer antigens that are part of an intact protein presented on the cancer cell surface. TCRs broaden the therapeutic approach by recognizing fragments on the cancer cell surface derived from intracellular proteins. By combining both CAR and TCR approaches, we have the potential to generate a broad portfolio of products that can target both solid and hematological tumors.

We have a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement, or CRADA, with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, as represented by the NCI, through which we are funding the research and development, including clinical trials, of eACT-based product candidates utilizing CARs and TCRs for the treatment of advanced solid and hematological malignancies. We believe our collaboration with the NCI allows us to identify promising CAR- and TCR-based product candidates for clinical testing. The NCI, with Dr. Rosenberg as the principal investigator, filed investigational new drug applications, or INDs, with the FDA in order to conduct clinical trials of CAR- and TCR-based product candidates. We will have to submit separate INDs to conduct our own clinical trials relating to these product candidates. Under the CRADA, we have an exclusive option to negotiate commercialization licenses from the National Institutes of Health, or the NIH, to intellectual property relating to CAR- and TCR-based product candidates developed in the course of the CRADA research plan.

We also have a Research Collaboration and License Agreement with Amgen Inc., or the Amgen Agreement, pursuant to which we and Amgen expect to develop and commercialize additional CAR-based product candidates directed against various targets contributed to the collaboration by Amgen. We received $60.0 million as an upfront payment pursuant to the Amgen Agreement, a portion of which we will pay to one of our licensors.

Our lead product candidate, KTE-C19, is an anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy. CD19 is a protein expressed on the cell surface of B cell lymphomas and leukemias. We are funding an ongoing NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trial utilizing anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy that is designed to establish a dose level and appropriate conditioning regimen, as well as to assess overall safety, in patients with B cell lymphomas and leukemias. The trial’s primary objective is to determine the safety and feasibility of the administration of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy. KTE-C19 will use the identical anti-CD19 CAR construct and viral vector that is being used in the NCI trial. However, we believe we have streamlined and optimized the NCI’s original manufacturing process of anti-CD19 CAR T cells for our KTE-C19 product candidate. In addition, the NCI has begun using the same manufacturing process that will be used for KTE-C19 in its ongoing Phase 1-2a clinical trial of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy. On December 12, 2013, we entered into an exclusive,

4

worldwide license agreement, including the right to grant sublicenses, with Cabaret Biotech Ltd., or Cabaret, and its founder relating to intellectual property and know-how owned or licensed by Cabaret and relating to CAR constructs that encompass KTE-C19. While we are funding the NCI trial pursuant to the CRADA, we do not expect to license intellectual property relating to KTE-C19 from the NIH.

As of November 30, 2014, the objective response rate of the 29 evaluable patients in the NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trial was 76%. Objective response occurs when there is a complete remission or a partial remission, as measured by standard criteria. Generally, a complete remission requires a complete disappearance of all detectable evidence of disease, and a partial remission typically requires at least approximately 50% regression of measurable disease, without new sites of disease. As of November 30, 2014, 16 of the 29 evaluable patients were in remission. Three of the 16 patients later experienced disease progression after their first treatment and subsequently reestablished remission after a second course of treatment and remain in remission. Severe and life threatening toxicities occurred mostly in the first two weeks after cell infusion and generally resolved within three weeks.

We are initially advancing KTE-C19, which has been granted orphan drug designation by both the FDA and the European Commission to treat DLBCL. The FDA designation may provide seven years of market exclusivity in the United States and the European Commission designation may provide ten years of market exclusivity in Europe, each subject to certain limited exceptions. However, the U.S. and European orphan drug designations do not convey any advantages in, or shorten the duration of, the regulatory review or approval process.

In the ongoing NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trial, 17 of the 29 evaluable patients had relapsed/refractory DLBCL, PMBCL or TFL. Eleven of these patients had an objective response to anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy and six did not respond to therapy. We are pursuing refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL, as our first target indications because of these promising initial NCI results and the commercial opportunity inherent in the significant unmet need of this patient population. DLBCL and follicular lymphoma, or FL, are the most common subtypes of NHL, accounting for approximately 30% and 20%, respectively, of the total 70,000 NHL patients diagnosed each year in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society. Conventional therapy for FL is not curative, and virtually all patients develop progressive disease and chemo-resistance. A pivotal event in the history of some patients with FL is histological transformation to more aggressive malignancies, most commonly DLBCL. We refer to the transformed FL as TFL. There are approximately 1,650 new cases of PMBCL in the United States each year. Patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL following treatment under the current standards of care have a particularly dire prognosis, with no curative treatment options.

We also plan to develop additional CAR-based product candidates. Currently, we are funding an NCI-sponsored Phase 1-2a clinical trial of a CAR-based T cell therapy targeting the EGFRvIII antigen in patients with glioblastoma, a highly malignant brain cancer. In addition, we expect to research and develop CAR-based product candidates pursuant to the Amgen Agreement.

Pursuant to the CRADA and through the NCI, we are also conducting or expect to conduct multiple NCI-sponsored Phase 2 and 1-2a clinical trials involving certain TCR-based T cell therapies, including those targeting SSX2, NY-ESO-1, MAGE and HPV antigens that are found on multiple cancers. We have license agreements with the NIH for intellectual property relating to TCR-based T cell therapies targeting SSX2, NY-ESO-1 and HPV antigens.

Recent Developments

Expansion of the CRADA

On February 24, 2015, we amended the CRADA to expand the research plan to include (1) the research and development of the next generation of TCR-based product candidates that are engineered to recognize neo-antigens, which are specific to the unique genetic profile of a patient’s own tumor, (2) the optimization of new methods to manufacture this next generation of TCR-based product candidates and (3) the advancement of CAR-based product candidates for the treatment of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and TCR-based product candidates for the treatment of certain epithelial tumors such as lung and colorectal cancer.

T-Cell Factory Acquisition

On March 17, 2015, we acquired T-Cell Factory, B.V., or TCF, a privately-held biotechnology company headquartered in the Netherlands, which was renamed Kite Pharma EU. The TCF acquisition has the potential to significantly expand our pipeline of TCR-based product candidates. Using its proprietary TCR-GENErator technology platform, TCF can rapidly and systematically discover tumor-specific TCRs. We believe this platform could generate a TCR-based product candidate that could enter the clinic as early as 2017.

The TCF acquisition also brings us expertise from Europe’s leading scientists in the field of T cell immuno-oncology as well as a strong partnership with the Netherlands Cancer Institute-Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, or NKI-AVL, which is the only dedicated cancer center in the Netherlands and maintains an important role as a national and international center of scientific and clinical expertise, development and training. Antonius Schumacher, Ph.D., a preeminent scientist in the field of T cell immuno-oncology, will serve as Chief Scientific Officer of Kite Pharma EU. Dr. Schumacher is currently Deputy Director and Principal Investigator of the NKI-AVL. TCF also has a license agreement with the NKI-AVL for know-how, materials and protocols, and the right of first negotiation of certain intellectual property rights with relevance to TCRs that may be developed in Dr. Schumacher’s lab at the NKI-AVL over the next five years.

5

Our Strategy

Our goal is to be a leader in immunotherapies with multiple cancer indications. To achieve this, we are developing a pipeline of eACT-based product candidates for the treatment of advanced solid and hematological malignancies. Key elements of our strategy are to:

Rapidly advance KTE-C19 through clinical development.

Based upon promising initial clinical results from the NCI Phase 1-2a trial, we plan to advance our lead product candidate, KTE-C19, for the treatment of patients with refractory aggressive NHL. We filed an IND in December 2014 and will initiate a Phase 1-2 single-arm multicenter clinical trial of KTE-C19 in patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. We anticipate patient enrollment to begin in the first half of 2015.

If we believe the data are compelling, we plan to discuss with the FDA the filing of a BLA for accelerated approval of KTE-C19 as a treatment for patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. The FDA may grant accelerated approval for product candidates for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need based on a surrogate or intermediate clinical endpoint, including tumor shrinkage, because such shrinkage is considered reasonably likely to predict a real clinical benefit of longer life. Assuming compelling data, we believe our accelerated approval strategy is warranted, given the limited alternatives for patients with refractory aggressive NHL. Even if accelerated approval is granted, confirmatory trials will be required. We plan to initiate a randomized confirmatory study in refractory aggressive NHL in order to fulfill likely post-marketing clinical study requirements to convert any accelerated approval to regular approval.

We also plan to begin Phase 2 clinical trials in 2015 for KTE-C19 in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, ALL and CLL. If we believe the data are compelling, we plan to pursue FDA approval for these indications.

Continue our collaborative relationship with the NCI to selectively identify and advance additional product candidates.

Our collaboration with the NCI provides us the opportunity to select products for oncology development based on human proof-of-concept data rather than preclinical animal data alone. We believe this approach will significantly reduce the risk in our development programs. We plan to select products for development based on a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio and proof-of-concept established in the clinic by the NCI. We believe with our NCI collaboration, we may assess the filing of at least one IND a year, exclusive of the NCI-related INDs, for the duration of the CRADA. We expect to file an IND relating to a TCR-based product candidate in late 2015 and an IND relating to an eACT-based product candidate in 2016. The CRADA has a five-year term expiring on August 30, 2017, and may be terminated earlier by the NCI. We have recently expanded our relationship with the NCI by amending the CRADA for the research and development of additional eACT-based product candidates, including the next generation of TCR-based product candidates directed against neo-antigens, and intend to continue to foster our strong relationship with the NCI.

Advance multiple eACT-based product candidates to allow for treatment on a patient-by-patient basis.

We believe the addition of other eACT-based product candidates to the pipeline would increase the cancer population coverage and allow us to leverage the expected manufacturing and development capabilities relating to KTE-C19.

We plan to exclusively license and develop a portfolio of TCR-based product candidates targeting various cancers based on data from the NCI Phase 2 clinical trial and Phase 1-2a clinical trials that we are funding under the CRADA. We also believe that the recent TCF acquisition has the potential to significantly expand our pipeline of TCR-based product candidates. We plan to develop a TCR-based product portfolio that targets specific antigens expressed by cancer cells irrespective of where the cancer originates. As a result, we believe this approach may allow for regulatory approvals of our personalized TCR-based product candidates without respect to cancer cell origin.

We also plan to develop additional CAR-based product candidates, including under the Amgen Agreement.

In addition, we may in-license, acquire, or invest in complementary businesses, technologies, products or assets to further expand our portfolio of eACT-based product candidates or to complement our eACT-based product candidates.

Establish commercialization and marketing capabilities of current and future pipeline products.

We have entered into a lease for a commercial manufacturing facility in El Segundo, which is adjacent to Los Angeles International Airport. We anticipate the El Segundo facility will be operational to support the planned commercial launch of KTE-C19 in 2017. Upon any regulatory approval of KTE-C19, we intend to build a focused specialty sales and marketing organization to commercialize KTE-C19. We expect to initially target the 50 highest volume transplant and lymphoma referral centers in the United States. We may also selectively partner with third parties to commercialize and market any approved product candidates outside the United States.

Engineered Autologous Cell Therapy (eACT)

White blood cells are a component of the immune system and are responsible for defending the body against infectious pathogens and other foreign material. There are several types of white blood cells, including T cells, natural killer cells, and B cells. T cells can be distinguished from other white blood cells by T cell receptors present on their cell surface. These receptors contribute to tumor

6

surveillance by helping T cells recognize cancerous cells. The T cell has the ability to kill the cancerous cell once it is identified. When the T cells with cancer-specific receptors are absent, present in low numbers, of poor quality or rendered inactive by suppressive mechanisms employed by tumor tissue, cancer may grow and spread to various organs. In addition, standard of care treatments can be deleterious to T cells’ ability to kill cancer. We believe eACT has the potential to treat cancer by overcoming the limits of a person’s immunosurveillance by increasing the effectiveness and number of a patient’s cancer-specific T cells.

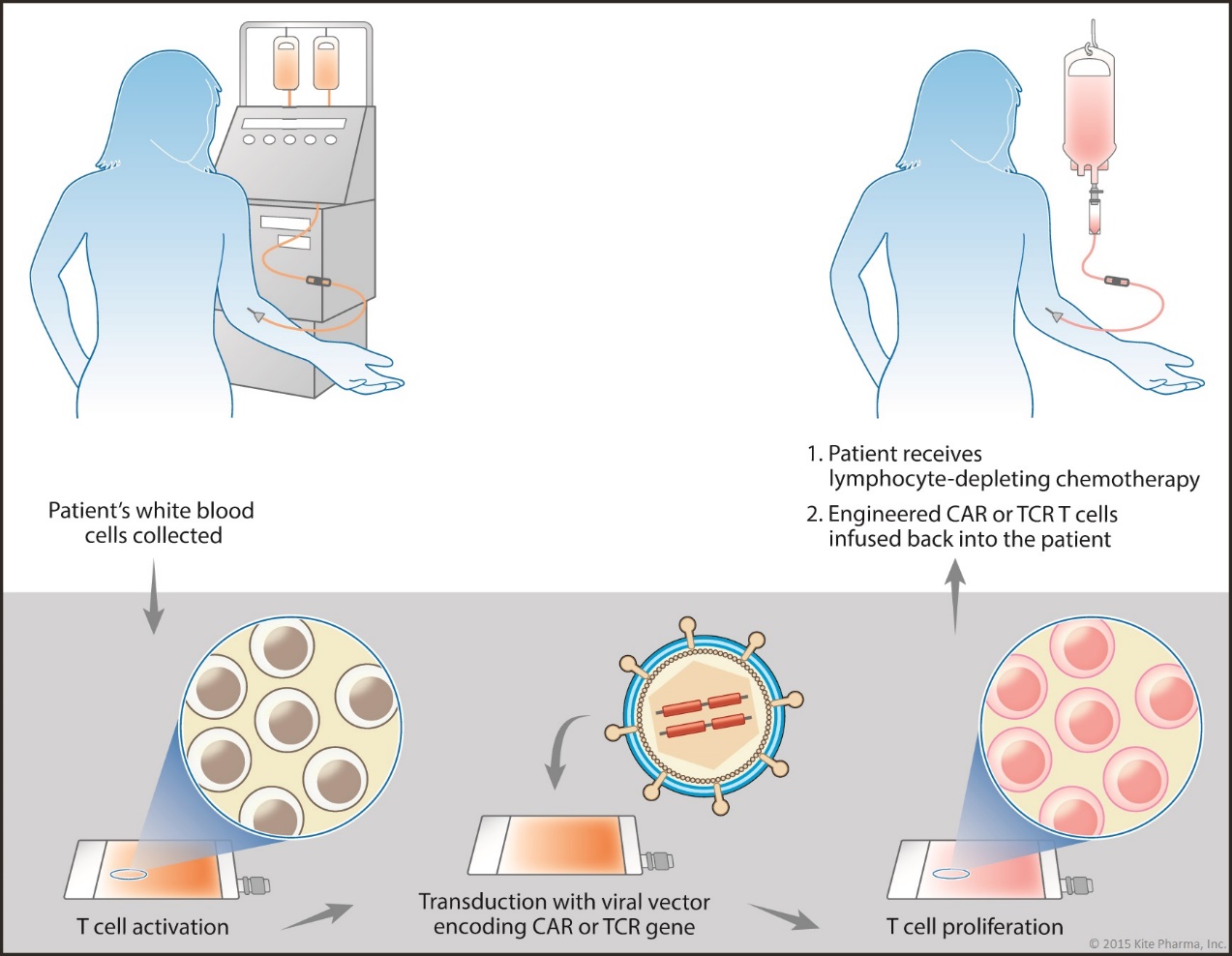

eACT involves (1) harvesting T cells from the patient’s blood, (2) genetically engineering T cells to express cancer-specific receptors, (3) increasing the number of engineered T cells and (4) infusing the functional cancer-specific T cells back into the patient. These cancer-specific T cells are engineered to recognize and kill cancer cells based on their specific protein targets. The T cell engineering process that we have developed, and are preparing to implement in our Phase 1-2 clinical trial, for KTE-C19, takes approximately two weeks from receipt of the patient’s white blood cells to infusion of the engineered T cells back to the patient. We intend to provide eACT to patients after they receive a short chemotherapy conditioning regimen, which is intended to improve the survival and proliferative capacity of the newly infused T cells.

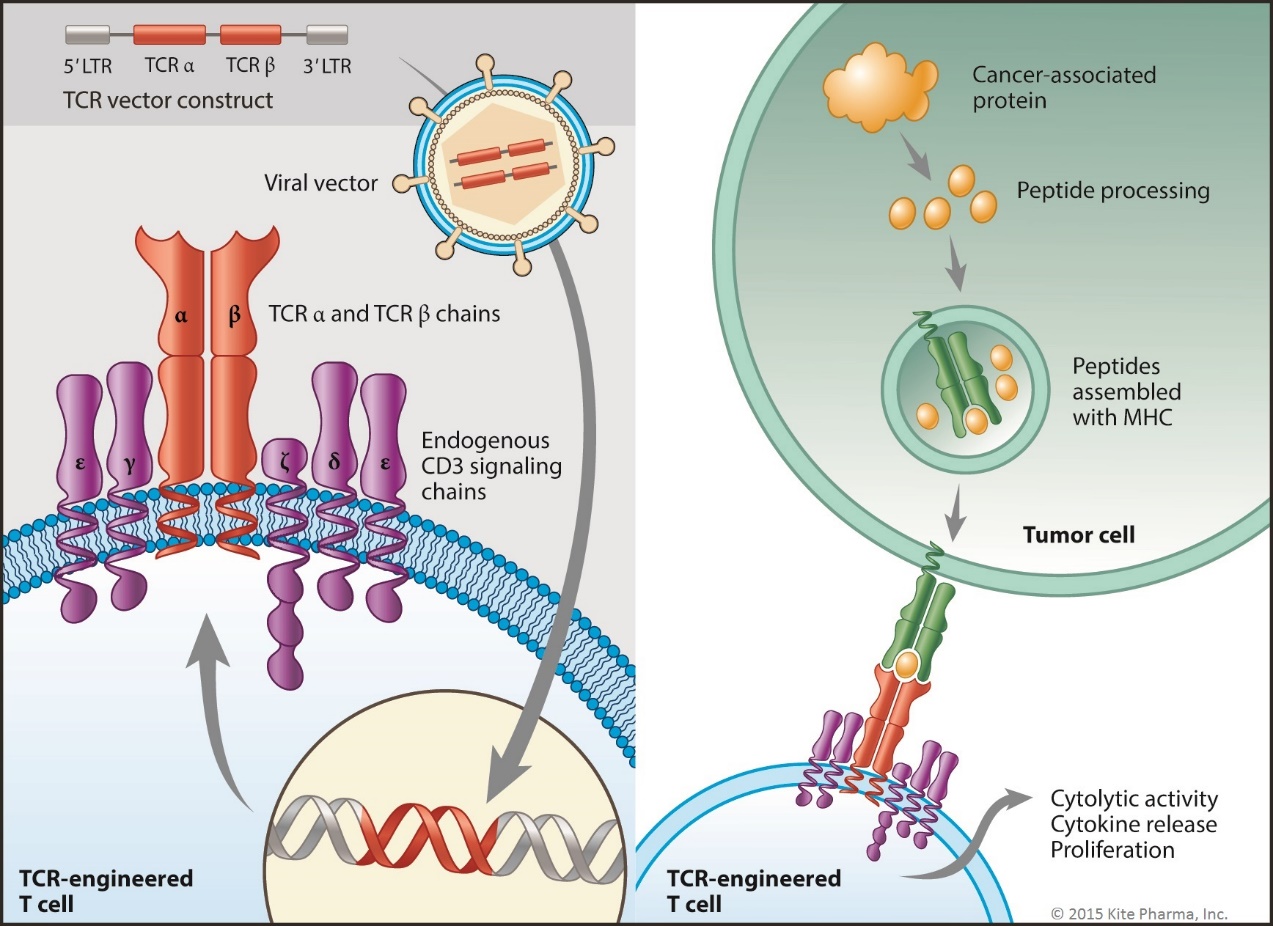

Using eACT technology, T cells can be genetically modified to express one of two classes of cancer-specific receptors: CARs or TCRs. CARs recognize native cancer antigens that are part of an intact protein on the cancer cell surface. TCRs broaden the therapeutic approach by targeting cancer proteins that reside inside the cancer cells. In ordinary cell metabolism, intracellular proteins are broken down into fragments called peptides. These peptides are then “displayed” on the cell membrane by a “presenting” molecule called major histocompatibility complex, or MHC. While T cells may not be able to recognize cancer-specific proteins inside a cancer cell, T cells that are engineered with TCRs are able to recognize a specific peptide from an intracellular protein when it is displayed on the cancer cell surface.

T cells engineered with CARs or TCRs can proliferate inside a patient and have the potential to infiltrate the microenvironment of a solid cancer mass, killing large numbers of cancer cells. Furthermore, we believe T cells engineered with CARs or TCRs can potentially overcome several mechanisms of tumor escape to which endogenous T cells may be susceptible. Upon activation, the T cells release cytokines, which contribute to the killing of cancer cells. However, excessive cytokine release can result in a systemic inflammatory reaction consisting of fever and low blood pressure.

CARs and TCRs are discussed in more detail below.

7

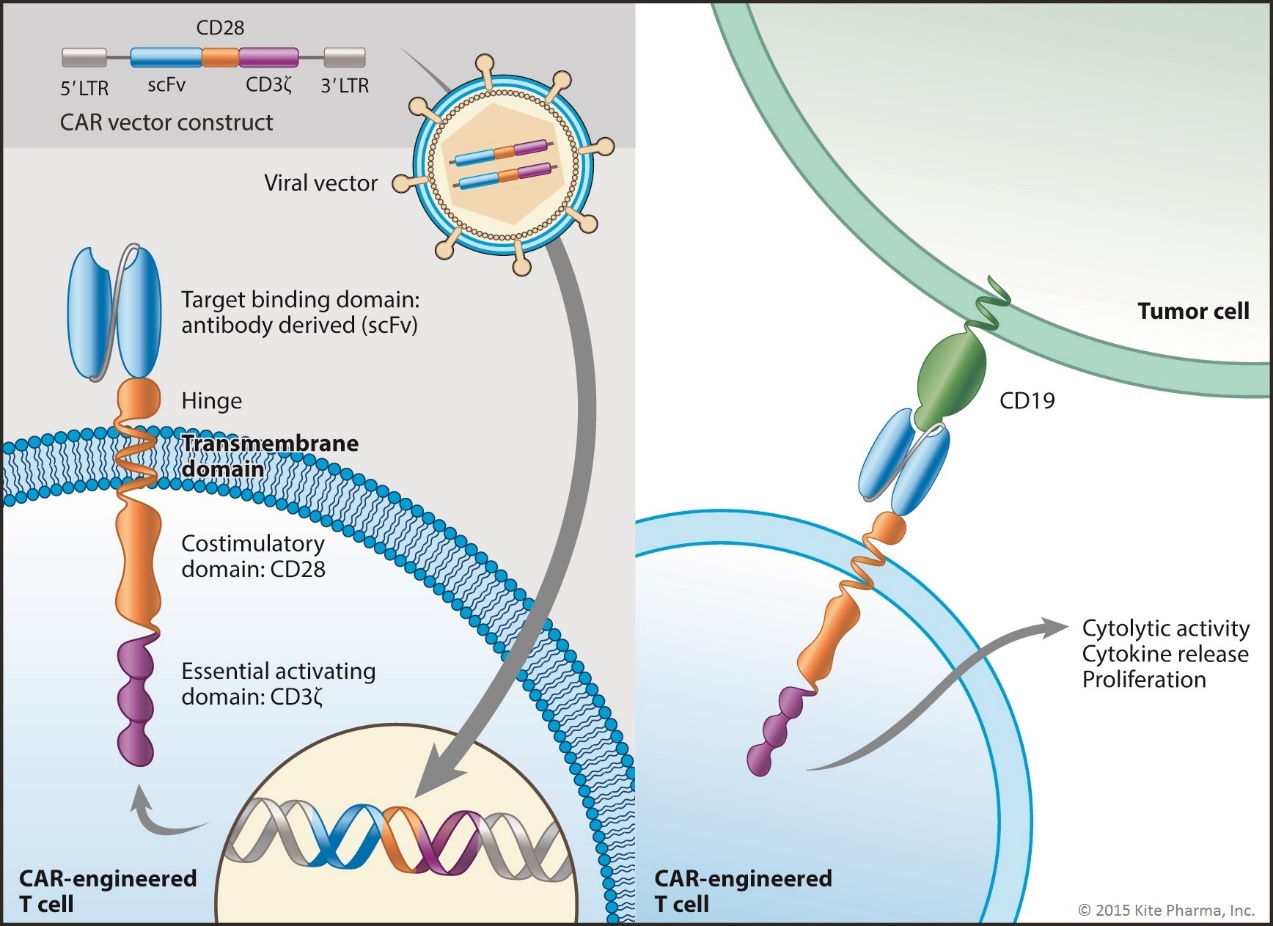

CARs

Engineering T cells with a CAR involves using a viral vector (a delivery vehicle) containing the CAR gene to transduce, or integrate, that gene into the T cell’s chromosomal make-up. The CAR gene encodes the single-chain CAR protein. The KTE-C19 CAR is comprised of the following elements:

|

● |

Target Binding Domain: At one end of the CAR is a target binding domain of an antibody that is specific to the target antigen CD19 on the cancer cell surface. This domain extends out of the engineered T cell into the extracellular space, where it can recognize target antigens. The target binding domain consists of a single-chain variable fragment, or scFv, of an antibody comprising variable domains of heavy and light chains joined by a short linker. This allows the expression of the CAR as a single-chain protein. |

|

● |

Transmembrane Domain and Hinge: This middle portion of the CAR links the scFv target binding domain to the activating elements inside the cell. This transmembrane domain “anchors” the CAR in the cell’s membrane. In addition, the transmembrane domain may also interact with other transmembrane proteins that enhance CAR function. In the extracellular region of the CAR, directly adjacent to the transmembrane domain, lies a “hinge” domain. This region of the CAR provides structural flexibility to facilitate optimal binding of the CAR’s scFv target binding domain with the target antigen on the cancer cell’s surface. |

|

● |

Activating Domains: Located within the T cell’s interior are two regions of the CAR responsible for activating the T cell upon binding to the target cell. The CD3z element delivers an essential primary signal within the T cell, and the CD28 element delivers an additional, co-stimulatory signal. Together, these signals trigger T cell activation, resulting in proliferation of the CAR T cells and direct killing of the cancer cell. In addition, T cell activation stimulates the local secretion of cytokines and other molecules that can recruit and activate additional anti-tumor immune cells. |

TCRs

Engineering T cells with a TCR involves using a viral vector containing TCR genes to transduce those genes into the T cell’s chromosomal makeup. The TCR genes encode two protein chains, which are designed to bind with specific peptides presented by MHC on the surface of certain cancer cells. The TCR protein chains are expressed on the T cell surface where they associate with CD3 proteins, which are natural components of the T cell. Upon binding of the TCR to the peptide-MHC complex on the cancer cell surface, the CD3 proteins deliver signals that trigger T cell activation, resulting in proliferation of the TCR T cells, direct killing of the cancer cell and stimulation of cytokines and other molecules that can recruit and activate additional anti-tumor immune cells.

8

TCR technology primarily targets cancer antigens that fall into two main categories: self-antigens and neo-antigens, also known as cancer-specific antigens. Self-antigens are generally shared across patients and include differentiation markers and cancer testis antigens, or CTAs. CTAs are expressed on a wide variety of common tumor types of various histological origins. We believe a subset of CTAs, which include SSX2, NY-ESO-1 and MAGE, are appropriate eACT targets because their expression on normal tissue is generally restricted to tissues that do not express MHC in adults. As a result, T cells engineered to target cells with such CTAs would target cancer cells rather than non-cancerous cells. We are initially focused on developing CTA-specific TCR-based product candidates. However, we have recently amended the CRADA to further the research and development of the next generation of TCR-based product candidates that would target neo-antigens, which are those derived from mutations arising in the tumor.

CAR and TCR Differences

There are three main differences between CARs and TCRs:

|

● |

MHC Restriction: Since TCRs recognize peptides only in the context of MHC molecules expressed on the surface of the target cell, their peptide specificity is termed MHC-restricted. In contrast, CAR target recognition is MHC-unrestricted. In humans, MHC molecules are known as human leukocyte antigen, or HLA, proteins. There are several HLA protein types which display genetic variation across the human population. As a result, a TCR-based product candidate would have to be matched to the HLA type of the patient. |

|

● |

Cancer Target Frequency: CARs recognize native cancer antigens that are part of an intact protein on the cancer cell surface. Bioinformatic studies predict that 20% to 30% of all encoded proteins may be extracellular or membrane-associated. TCRs broaden the therapeutic approach by recognizing specific peptides of intracellular proteins that are displayed on the cancer cell surface in combination with MHC. |

|

● |

Antigen-Presenting Cell Recognition: As opposed to CARs, TCRs have the potential to recognize cancer antigens not only presented directly on the surface of cancer cells but also presented by antigen-presenting cells in the tumor microenvironment and in secondary lymphoid organs. Antigen-presenting cells are native immune-system cells responsible for the amplification of the immune response. |

Other Immunotherapies

Immuno-oncology is one of the most actively pursued areas of research by biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies today. Over the past few decades, several novel treatment methodologies have emerged that modulate the immune system including vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. Therapeutic vaccines have historically been associated with modest efficacy in the treatment of cancer. They commonly utilize dendritic cells, a form of immune cell that presents tumor antigens to T cells, which can result in T cell activation. Similarly, monoclonal antibodies, after binding a cancer antigen, classically utilize an effector arm in order to stimulate an immunological response.

9

More recently, interest and excitement has centered around the use of bi-specific antibodies and checkpoint inhibitors. Bi-specific antibodies commonly target both the cancer antigen and T cell receptor, thus bringing both cancer cells and T cells in close proximity to maximize the likelihood of an immune response to the cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors, or CPIs, work by releasing the body’s natural “brakes” on the immune system. Tumors can evade immune surveillance by triggering co-inhibitory receptors that can blunt T cell effectiveness and proliferation. By targeting these receptors, CPIs release these brakes, thereby reactivating T cells. Both bispecific antibodies and CPIs require functioning T cell populations in order to exert their effect.

We believe our eACT presents a promising innovation in immunotherapy by focusing directly on the key immune mediator, the T cell. Our genetically engineered T cells bind to cancer cells directly, and as such, have the potential to kill a substantial number of tumor cells. In addition, we note that eACT may be synergistic with other forms of immunotherapy. As an example, eACT may potentially be used in combination with CPIs to enhance efficacy.

Our Product Pipeline

We are developing a pipeline of eACT-based product candidates for the treatment of advanced solid and hematological malignancies, as shown below.

(1) Clinical trials being conducted by the NCI pursuant to the CRADA.

10

KTE-C19

Overview

We are initially developing KTE-C19 for the treatment of refractory aggressive NHL. NHL is a cancer of white blood cells, including B cells. CD19 is expressed on the surface of B cells, including malignant B cells, and it is not expressed on any other tissue. B cells are considered non-essential tissue, as they are not required for patient survival. We believe CD19 is an appropriate target for the treatment of all types of B cell leukemias and lymphomas.

Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma, Primary Mediastinal B cell Lymphoma and Transformed Follicular Lymphoma

We expect initially to develop and seek approval of KTE-C19 for the treatment of patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. According to the American Cancer Society, DLBCL is the most common subtype of NHL, accounting for approximately 30% of the total 70,000 NHL patients diagnosed each year in the United States. It is classified as an aggressive lymphoma, in which survival is measured in months rather than years.

First line therapy for patients with DLBCL usually consists of chemotherapy regimen known as R-CHOP (rituximab, cytoxan, adriamycin, vincristine and prednisone), which includes the use of a monoclonal antibody known as rituximab. Approximately 50% to 60% of DLBCL patients are cured with first line therapy.

For patients who relapse or are refractory to first line therapy, the current standard of care for second line therapy consists of a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen with rituximab. These second line chemotherapy regimens are either R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide) or R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine and cisplatin).

Patients who respond to second line therapy may go on to receive hematopoietic cell transplantation, or HCT. Patients who do not respond to second line therapy or relapse after HCT are treated with a third line salvage chemotherapy. These patients have a poor prognosis and treatment is generally palliative with no curative treatment options.

Follicular lymphoma, or FL, is the second most common type of NHL and the most common type of indolent NHL, or iNHL. There are approximately 15,300 new diagnoses of FL in the United States each year. Conventional therapy for FL is not curative, and virtually all patients develop progressive disease and chemo-resistance. A pivotal event in the history of some patients with FL is histological transformation to more aggressive malignancies, most commonly DLBCL.

Due to differences in clinicopathologic features and treatment regimens, PMBCL can be considered a different patient population to DLBCL. There are approximately 1,650 new cases of PMBCL in the United States each year. Patients can be generally classified as having either limited stage or advanced stage disease. Limited stage disease can be contained within one irradiation field. In contrast, advanced stage disease refers to disease that cannot be contained within one irradiation field, bulky disease (greater than ten centimeter wide tumors), and tumors that have an associated pericardial or pleural effusion. Patients of advanced stage disease are typically treated with induction chemoimmunotherapy. Primary refractory disease occurs when initial therapy fails to achieve a complete response and the general approach is to administer systemic chemotherapy with or without rituximab with plans to proceed to high-dose chemotherapy and HCT in those with chemotherapy-sensitive disease. The treatment of patients who are not candidates for HCT, who fail to respond to second line chemotherapy regimens, or who relapse after HCT is generally palliative. Salvage therapy is rarely curative.

Other Lymphomas and Leukemias

We also expect to develop and seek regulatory approval of KTE-C19 for the treatment of other lymphomas and leukemias, including MCL, CLL and ALL.

There are approximately 4,100 new cases of MCL in the United States each year. Therapy for MCL is not curative, and virtually all patients will have refractory or recurrent disease. Treatment of MCL is difficult due to the rapid development of resistance to therapy.

CLL is the most common leukemia, with approximately 15,000 new cases in the United States per year. It is characterized by a progressive accumulation of functionally incompetent lymphocytes which are monoclonal in origin. Most patients with CLL will have an initial complete or partial response to chemotherapy, but relapse invariably occurs after treatment discontinuation unless the patient undergoes allogeneic HCT, which is the only known curative therapy. Almost all patients with CLL will develop refractory disease.

ALL is another main type of leukemia and has an aggressive course. Approximately 6,000 patients are diagnosed with ALL in the United States each year. Approximately 90% of patients with ALL will demonstrate a complete remission with intensive induction chemotherapy. However, after consolidation and maintenance therapy, the majority of patients will relapse in the bone marrow. Although approximately half of patients with relapsed ALL will obtain a second complete remission, most will eventually die from leukemia. The prognosis of patients with relapsed or refractory ALL is poor, with median survival less than one year.

11

Clinical Experience

We are funding a Phase 1-2a clinical trial of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy that is being conducted by the NCI, with Dr. Steven A. Rosenberg as the principal investigator. The anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy is being administered to patients with CD19-positive B cell malignancies. The trial’s primary objective is to determine the safety and feasibility of the administration of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy with a conditioning regimen that does not include any stem cell transplantation, or myeloablative, conditioning regimen in patients with B cell malignancies. The trial’s secondary objectives are to determine (1) the in vivo survival of the anti-CD19 CAR transduced T cells and (2) if the treatment regimen causes regression of B cell malignancies. As of November 30, 2014, a total of 32 patients had been treated, including three patients who received two doses of the CAR T cells. Most patients received at least four lines of prior therapy, and among the 17 evaluable patients with DLBCL, TFL or PMBCL, 76% were chemotherapy refractory and 24% had relapsed after autologous stem cell transplant.

Three groups of patients have been treated to November 30, 2014. Group 1 consisted of eight patients, including one patient who was retreated, treated with various doses of CAR T cells following a conditioning regimen consisting of high dose cyclophosphamide for two days followed by fludarabine for five days. These patients also received high dose Interleukin-2 after the CAR T cell administration to stimulate their proliferation. Group 2 consisted of 15 patients, including two patients from group 1 who were retreated, who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine and no Interleukin-2 following the CAR T cell administration. After these 21 patients were treated, the doses of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine were reduced to improve the tolerability of the regimen for group 3. As of November 30, 2014, 11 patients have received CAR T cells using the reduced intensity conditioning regimen in group 3.

Efficacy

The 32 patients received a total of 35 infusions of anti-CD19 CAR, as three patients were retreated upon eventual cancer progression after the first dose of CAR T cells. Of the 32 patients who were treated, two were not evaluable for efficacy due to death prior to the first response evaluation, as noted below, and one other had been treated but had not yet reached the one month follow-up disease assessment and therefore was not yet evaluated.

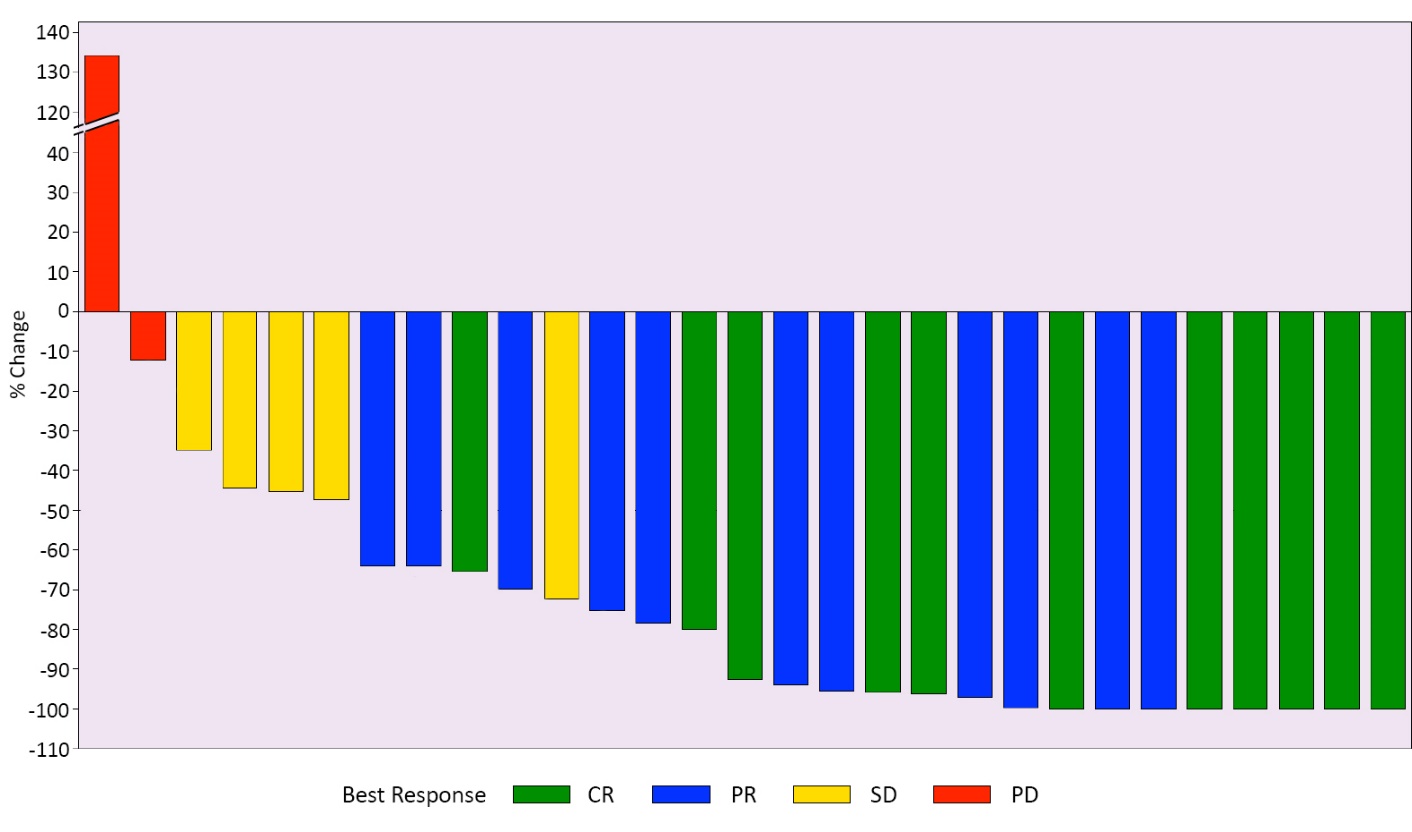

For the 29 evaluable patients, the objective response rate was 76%. Objective response occurs when there is a complete remission or a partial remission, as measured by standard criteria. Generally, a complete remission requires a complete disappearance of all detectable evidence of disease, and a partial remission typically requires at least approximately 50% regression of measurable disease, without new sites of disease. The greatest change in shrinkage of the tumor masses for each evaluable patient is shown in the following chart.

Waterfall Plot of Tumor Shrinkage

12

Tumor responses tended to occur relatively early after conditioning and anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy, typically at the first follow-up scan at month one. As of November 30, 2014, 16 of the 29 evaluable patients were in remission. Three of the 16 patients later experienced disease progression after their first treatment and subsequently reestablished remission after a second course of treatment and remain in remission.

We believe these results are compelling in heavily pretreated patients, most of whom had received at least four lines of prior therapy.

Safety

When the patients received the CAR T cells, all of them had low blood counts due to the chemotherapy conditioning regimen. The most prominent acute toxicities included symptoms thought to be associated with the release of cytokines, such as fever, low blood pressure and kidney dysfunction. Some patients also experienced toxicity of the central nervous system, such as confusion, somnolence, and speech impairment. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities occurred mostly in the first two weeks after cell infusion and generally resolved within three weeks.

The following table summarizes the adverse events by worst grade attributed to the CAR T cell infusion in the 32 patients treated as of November 30, 2014, with Grade 2 representing moderate toxicity, Grade 3 representing severe toxicity and Grade 4 representing life threatening toxicity. Grade 5 toxicity represents toxicity resulting in death and no occurrences of Grade 5 toxicity were related to the CAR T cell infusion.

Summary of Adverse Events related to Anti-CD19 CAR T Cells by Worst Grade

|

Organ |

Adverse Event |

Grade 2-5 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

|

Any |

Any |

20 (63%) |

6 (19%) |

8 (25%) |

|

Cardiac |

Hypotension |

7 (22%) |

2 (6%) |

3 (9%) |

|

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Constitutional Symptoms |

Fever (in the absence of neutropenia) |

5 (16%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Metabolic / Laboratory |

Creatinine |

4 (13%) |

1 (3%) |

2 (6%) |

|

Neurology |

Ataxia |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Confusion |

3 (9%) |

2 (6%) |

0 (0)% |

|

|

Encephalopathy |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Cranial neuropathy |

2 (6%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Motor neuropathy |

2 (6%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Pyramidal tract dysfunction |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (3%) |

|

|

Somnolence |

3 (9%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (9%) |

|

|

Aphasia/Dysphasia |

5 (16%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (6%) |

|

|

Syncope |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Tremor |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Pulmonary / Upper Respiratory |

Dyspnea |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Hypoxia |

2 (6%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Renal / Genitourinary |

Low Urine Output |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Vascular |

Acute vascular leak syndrome |

1 (3%) |

1 (3%) |

0 (0%) |

Patients in this clinical trial received cell doses ranging from 1-30 million cells per kilogram of body weight. Although the regimens were adjusted during the trial in response to toxicity, it is not yet clear how toxicity is related to cell dosage and conditioning chemotherapy.

Patients chosen for the clinical trial generally had a poor prognosis and several patients in the trial died. However, the causes of death were not attributed to the CAR T cells.

13

Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy can result in long-term B cell depletion that may require patients to receive periodic doses of gammaglobulin to help prevent infections. However, B cells are considered to be non-essential tissue, as they are not required for patient survival.

In a separate Phase 1 dose escalation study conducted by the Pediatric Oncology Branch of the NCI, administration of anti-CD19 CAR T cells resulted in a 70% complete response rate in 20 pediatric or young adult patients with relapsed/refractory ALL. Sixty percent of the 20 patients achieved a minimal residual disease, or MRD, negative complete response. Ten of the patients who had an MRD-negative complete response subsequently underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, and all 10 remained disease free. The study’s primary objectives were to determine maximum tolerated dose, feasibility and toxicity. As seen in the Phase 1-2a clinical trial described above, infusion of anti-CD19 CAR T cells was associated with significant, acute toxicities, including febrile neutropenia, cytokine release syndrome, chemical laboratory abnormalities, low blood counts and transient neurological deficits.

Preclinical Experience

Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy has been explored in both in vitro and animal studies, with positive results. In the laboratory, in vitro studies demonstrated robust killing activity by anti-CD19 CAR T cells of human CD19-positive target cells. Additionally, in a fully immune-competent mouse lymphoma model, anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion resulted in profound and durable tumor regression and long-term disease-free survival. Mice that received T cells expressing a CAR with irrelevant specificity, or no T cells at all, rapidly developed large lymphoma masses and extensive metastatic lymphoma in spleen and lymph nodes. Other mice studies revealed that irradiation before anti-CD19 CAR T cell transfer was critical for anti-tumor activity.

In the mice studies, no toxicities associated with anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy were observed, except for a complete and extended depletion of normal B cells after anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy.

Development Strategy

We will initiate a Phase 1-2 single-arm multicenter clinical trial of KTE-C19 in approximately 120 patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. We expect the clinical trial to be conducted at approximately 25 sites, with objective response rate as the primary endpoint. In the Phase 2 portion of the trial, we expect to treat approximately 72 patients with DLBCL in cohort one and approximately 40 patients with PMBCL and TFL in cohort two. We expect the Phase 2 enrollment to take approximately 12 months from commencement of the Phase 2 portion. We plan to conduct an interim analysis of cohort one after 50 patients are treated. If we believe the data are compelling and show a convincing benefit-to-risk ratio compared to historical data, we plan to file a BLA for accelerated approval of KTE-C19 as a treatment for patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL.

We plan to initiate a randomized confirmatory study in refractory aggressive NHL in order to fulfill likely post-marketing clinical study requirements to convert any accelerated approval to regular approval. The design of this randomized confirmatory study has yet to be confirmed pending regulatory discussion and emerging clinical data. This study is planned to be ongoing at the time of the expected BLA approval for accelerated approval in refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. If the randomized confirmatory study demonstrates a clinically and statistically significant survival benefit, and assuming approval of the BLA, we would plan to file a Biologics License Supplement, or BLS, for regular approval.

We also plan to begin Phase 2 clinical trials in 2015 for KTE-C19 in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, ALL and CLL. If we believe the data are compelling, we plan to pursue FDA approval for the additional indications.

Additional eACT-Based Product Candidates

Pursuant to the CRADA, we are funding an NCI Phase 2 and multiple NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trials involving certain CAR- and TCR-based T cell therapies. We expect to select CAR- and TCR-based product candidates for development based on data from these clinical trials. Our collaboration with the NCI provides us the opportunity to select products for oncology development based on human proof-of-concept data rather than preclinical animal data alone. We believe this approach will significantly reduce the risk in our development programs. We plan to select product candidates for further development based on a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio and proof-of-concept established in the NCI clinical trials.

We also expect that the Amgen Agreement will expand our CAR-based product candidate pipeline and that our recent acquisition of TCF will potentially significantly expand our TCR-based product candidate pipeline.

14

CAR-Based Product Candidates

We may seek to develop additional CAR-based product candidates. Currently, we are funding an NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trial of a CAR-based T cell therapy targeting the EGFRvIII antigen in patients with glioblastoma, a highly malignant brain cancer. The NCI is conducting this trial at the NIH. The trial’s primary objectives are to (1) evaluate the safety of the administration of anti-EGFRvIII CAR T cell therapy in patients receiving the nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, and Interleukin-2 and (2) determine the six month progression free survival of patients receiving anti-EGFRvIII CAR T cell therapy and Interleukin-2 following a nonmyeloablative but lymphoid depleting preparative regimen. The trial’s secondary objectives are to (1) determine the in vivo survival of the gene-engineered cells and (2) evaluate radiographic changes after treatment to measure objective tumor response. Patients are currently being enrolled into the Phase 1 dose escalation part of the trial and no results from this trial have been published.

TCR-Based Product Candidates

Pursuant to the CRADA, we are funding or expect to fund NCI Phase 2 and 1-2a clinical trials involving TCR-based T cell therapies targeting SSX2, NY-ESO-1, MAGE and HPV antigens. These antigens are found on multiple cancers. The NCI Phase 2 clinical trial of a TCR-based therapy targeting the NY-ESO-1 antigen is being conducted at the NIH. The trial’s primary objective is to determine whether the administration of anti-NY-ESO-1 plus high-dose Interleukin-2 following a nonmyeloablative lymphoid depleting preparative regimen may result in objective tumor regression in patients with metastatic cancers that express the NY-ESO-1 antigen. The trial’s secondary objectives are to (1) determine the in vivo survival of the gene engineered cells and (2) determine the toxicity profile of this treatment regimen. Patients are currently being enrolled into the dose escalation part of the trial and no results from this trial have been published.

Two NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trials of TCR-based therapies targeting the MAGE antigen are being conducted at the NIH. One trial’s primary objectives are to determine (1) a safe dose of the administration of autologous T cells transduced with an anti-MAGE-A3/A6, which is HLA-DP0401/0402 restricted, or MAGE-A3-DP4, TCR and Interleukin-2 to patients following a nonmyeloablative but lymphoid depleting preparative regimen, (2) if this approach will result in objective tumor regression in patients with metastatic cancer expressing MAGE-A3-DP4 and (3) the toxicity profile of this treatment regimen. This trial’s secondary objective is to determine the in vivo survival of gene-engineered cells. The second trial’s purpose is to see if the anti-MAGE-A3, which is HLA-A1 restricted, cells cause tumors to shrink and to assess safety. Patients are currently being enrolled into the Phase 1 dose escalation part of each of the trials and no results from either trial have been published.

A planned NCI Phase 1-2a clinical trial of a TCR-based therapy targeting the SSX2 antigen has not yet begun.

The NCI Phase 1-2 clinical trial of a TCR-based therapy targeting the HPV-16 E6 antigen relating to certain cancers associated with the human papillomavirus is being conducted at the NIH. The trial’s primary objectives are to determine (1) a safe dose of administration of autologous T cells transduced with an anti-HPV-16 E6 TCR and aldesleukin to patients following a nonmyeloablative but lymphodepleting preparative regimen and (2) the objective tumor response rate and duration in patients with metastatic or recurrent or refractory HPV-16+ cancers treated with this regimen. The trial’s secondary objective is to determine the toxicity of the treatment regimen and to study immunologic correlates associated with E6 TCR gene therapy for HPV-16+ cancers. Patients are currently being enrolled into the dose escalation part of the trial and no results from this trial have been published. Christian Hinrichs is the principal investigator of this trial.

With respect to developing a TCR-based product portfolio, we plan to use a novel Phase 2 design wherein patients with various cancers will be screened for tumor antigen expression as well as the patient specific HLA proteins that present the tumor antigen on the cancer cell surface. Patients will then be assigned a TCR-based therapy that matches both the tumor antigen expression and their presenting HLA protein. We believe this approach may allow for regulatory approvals of our personalized TCR-based product candidates without respect to cancer cell origin. As a result, we may be able to select the appropriate treatment from a portfolio of TCR-based product candidates on a patient-by-patient basis.

Preclinical Experience

While we are currently funding NCI Phase 2 and 1-2a clinical trials involving TCR-based T cell therapies, we have strong preclinical data supporting the potential efficacy of multiple TCR-based T cell therapies. For example, several different SSX2-specific TCR genes were screened for their expression and ability to specifically recognize SSX2-expressing cancer cells of a variety of histologies. Based on superior expression, potency and selective activity, an SSX2 TCR was identified as an attractive candidate for subsequent clinical evaluation. In addition to enabling us to select amongst different human TCR genes that target the same antigen, such preclinical studies allow us to make critical decisions regarding utilization of TCR genes derived from humans or mice, or otherwise engineered to optimize function. For instance, preclinical studies have demonstrated that a mouse derived, or murine, TCR targeting the antigen NY-ESO-1 was equivalent to or better than the comparable human-based NY-ESO-1 TCR with respect to stable expression, cytokine production and target cell killing. Compared to certain human TCR protein chains, those that are fully or partially murine, may be less likely to become entwined with endogenous human TCR protein chains, and as such, may be both more effective and selective in vivo.

15

Manufacturing, Processing and Delivering to Patients

Our manufacturing and processing of eACT product candidates is based on an improved version of the NCI’s original manufacturing and processing of engineered T cells. For KTE-C19, we will use the identical anti-CD19 CAR construct and viral vector that is being used in the ongoing NCI clinical trial. We believe we have streamlined and optimized the NCI’s original process, such as by removing human serum from the process to minimize risk of viral contamination, moving process steps from an open system to a closed system to minimize the risk of other contamination and standardizing the viral transduction process to help eliminate processing inconsistencies. In July 2014, the NCI submitted an IND amendment to use our streamlined and optimized process, and as of November 30, 2014, the NCI has treated four patients with T cells prepared by the new process.

Because it is important to rapidly treat patients with highly aggressive cancers, we have developed, and are preparing to implement in our Phase 1-2 clinical trial, a T cell engineering process for KTE-C19 that takes approximately two weeks from receipt of the patient’s white blood cells to infusion of the engineered T cells back to the patient. The processing of our lead product candidate, KTE-C19, begins with the collection of the patient’s white blood cells using a standard blood bank procedure. The collected cells are then sent to a central processing facility, where the peripheral blood mononuclear cells, including T cells, are isolated from the other sample components. These cells are stimulated to proliferate, then transduced with a retroviral vector to introduce the CAR gene into the patient’s T cells. These engineered cells are then propagated in cell culture bags until sufficient cells are available for infusion back into the patient. The engineered T cells are then washed and frozen at the cell processing site, and shipped back to the clinical center where they can be administered to the patient. In preparation for administration of the engineered T cells, the patient undergoes a short chemotherapy conditioning regimen, which is intended to improve the survival and proliferative capacity of the newly infused T cells.

We expect Progenitor Cell Therapy, LLC, or PCT, to process KTE-C19 for our clinical trials in patients with refractory DLBCL, PMBCL and TFL. Cell processing activities are conducted at PCT under current good manufacturing processes, or cGMP, using qualified equipment and materials. We have engaged a third-party contractor to manufacture the retroviral vector that delivers the applicable CAR gene into the T cells under cGMP. We believe all materials and components utilized in the production of the retroviral vector and final T cell product are readily available from qualified suppliers.

We expect to rely on PCT to meet anticipated clinical trial demands. In the future, we may rely on PCT or other third parties, and expect to develop our own manufacturing capabilities for the manufacturing and processing of eACT-based product candidates for our clinical trials. We have recently leased a clinical manufacturing facility near our headquarters in Santa Monica, California.

To meet projected needs for commercial sale quantities, we intend to develop our own commercial manufacturing facility to supply and process products on a patient-by-patient basis. We have entered into a lease for a commercial manufacturing facility in El Segundo, which is adjacent to Los Angeles International Airport. We anticipate the El Segundo facility will be operational to support the planned commercial launch of KTE-C19 in 2017. Developing our own manufacturing capabilities may require more costs than we anticipate or result in significant delays. If we are unable to develop our own manufacturing capabilities, we will rely on contract manufacturers, including both current and alternate suppliers, to ensure sufficient capacity is available for commercial purposes prior to the filing of a BLA.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual property is of vital importance in our field and in biotechnology generally. We seek to protect and enhance proprietary technology, inventions, and improvements that are commercially important to the development of our business by seeking, maintaining, and defending patent rights, whether developed internally or licensed from third parties. We will also seek to rely on regulatory protection afforded through orphan drug designations, data exclusivity, market exclusivity and patent term extensions where available.

To achieve this objective, a strategic focus for us has been to identify and license key patents that provide protection and serve as an optimal platform to enhance our intellectual property and technology base. Well before the field of adoptive T cell immunotherapy raised commercial interest and started its transition to an industrial environment, we initiated a process of identifying patents with broad coverage in the area of CARs. Between 2009 and 2013, we identified, and ultimately licensed, issued patents with broad claims directed to the CAR concept. These patents were originally filed by investigators at the Weizmann Institute of Science, the NIH, University of California San Francisco, or UCSF, and Cell Genesys. As the ownership of some of these patents was complex and shared by multiple institutions, it took a significant interval of time and effort for us to complete their exclusive licensing. This process was finalized in December 2013.

This effort was paralleled by the creation and execution in August 2012 of the CRADA. As discussed below under “—Our Research and Development and License Agreements,” this agreement provides the framework under which we may license product-related intellectual property to support our pipeline development and commercialization activities, as well as enhance and extend the life-time of our patent portfolio.

Our intellectual property estate strategy is designed to provide multiple layers of protection, including: (1) patent rights with broad claims directed to core CAR constructs used in our products; (2) patent rights covering methods of treatment for therapeutic indications; (3) patent rights covering specific products; and (4) patent rights covering innovative manufacturing processes and methods for generating new constructs for genetically engineering T cells.

16

We believe our current layered patent estate, together with our efforts to develop and patent next generation technologies, provides us with substantial intellectual property protection. We have conducted extensive freedom to operate, or FTO, analyses of the current patent landscape with respect to our lead product candidate, and based on these analyses we believe that we have FTO for KTE-C19. However, the area of patent and other intellectual property rights in biotechnology is an evolving one with many risks and uncertainties.

Our current patent estate includes an exclusive license to a patent portfolio owned by Cabaret and directed to CAR constructs developed by Dr. Zelig Eshhar, Yeda-Weizmann, NIH, UCSF and Cell Genesys. Our CAR construct-directed patent portfolio includes 10 issued U.S. patents, seven of which are directed to core construct composition of matter and two of which are directed to methods of treatment for therapeutic indications. These patents first begin to expire in April 2015, with the last of these patents, which broadly claims scFv-based CAR constructs and is also our most significant CAR-related patent, expiring in 2027. These patents represent all of the material patents underlying KTE-C19. We are working to develop the next generation of CAR and TCR technologies for use in this field, which we intend to patent on our own or to license from our collaborators, to expand this layer of our intellectual property estate. We expect to file patent applications directed to these technologies as early as mid-2015.

Our current patent estate also includes an exclusive license from the NIH to patent applications related to CAR-based product candidates that target the EGFRvIII antigen for the treatment of brain cancer, head and neck cancer, and melanoma and TCR-based product candidates that target the CTA SSX2 for treatment of head and neck cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, prostate cancer, and sarcoma. Our patent estate further includes a co-exclusive license to these same product candidates for the treatment of certain other cancer types. We also have exclusive licenses from the NIH to patent applications related to TCR-based product candidates that target the NY-ESO-1 antigen and certain HPV antigens.

The identification of new technologies and initiation of the exclusive licensing process occur under the framework of the CRADA between us and the NIH. Our product-specific intellectual property licensed to date includes four Patent Cooperation Treaty applications with priority dates in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013, three corresponding U.S. non-provisional patent applications, and corresponding foreign patent applications in Canada, Australia, Europe, China, Israel and Japan, as well as one pending U.S. provisional patent application. The Patent Cooperation Treaty application with the 2010 priority date relates to our TCR-based product candidates targeting the SSX2 antigen, the Patent Cooperation Treaty application with the 2011 priority date relates to our CAR-based product candidate targeting the EGFRvIII antigen, the Patent Cooperation Treaty application with the 2012 priority date relates to our TCR-based product candidates targeting the NY-ESO-1 antigen, and the Patent Cooperation Treaty application with the 2013 priority date relates to our TCR-based product candidates targeting HPV antigens. We may require an additional license relating to the EGFRvIII scFv target binding site in order to commercialize a CAR-based product candidate that targets the EGFRvIII antigen. We have no rights to any issued patents covering TCR-based product candidates.

Under the Amgen Agreement, we have a license to intellectual property rights to certain Amgen cancer targets. In addition, with our recent acquisition of TCF, we have certain intellectual property rights related to the TCR GENE-rator platform. See “—Our Research and Development and License Agreements—Amgen Agreement” and “—T Cell Factory Acquisition” for additional information.

Our strategy is also to develop and obtain additional intellectual property covering innovative manufacturing processes and methods for genetically engineering T cells expressing new constructs. To support this effort, we have established expertise and development capabilities focused in the areas of preclinical research and development, manufacturing and manufacturing process scale-up, quality control, quality assurance, regulatory affairs and clinical trial design and implementation. We have filed a Patent Cooperation Treaty application, jointly with the NCI, relating to eACT closed manufacturing process, and expect to continue to file patent applications to expand this layer of our intellectual property estate.

The term of individual patents depends upon the legal term of the patents in the countries in which they are obtained. In most countries in which we file, the patent term is 20 years from the date of filing of the first non-provisional application to which priority is claimed. In the United States, a patent’s term may be lengthened by patent term adjustment, which compensates a patentee for administrative delays by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in granting a patent, or may be shortened if a patent is terminally disclaimed over an earlier-filed patent. The term of a patent that covers an FDA-approved drug may also be eligible for a patent term restoration of up to five years under the Hatch-Waxman Act, which is designed to compensate for the patent term lost during the FDA regulatory review process. The length of the patent term restoration is calculated based on the length of time the drug is under regulatory review. A patent term restoration under the Hatch-Waxman Act cannot extend the remaining term of a patent beyond a total of 14 years from the date of product approval and only one patent applicable to an approved drug may be restored. Moreover, a patent can only be restored once, and thus, if a single patent is applicable to multiple products, it can only be extended based on one product. Similar provisions are available in Europe and certain other foreign jurisdictions to extend the term of a patent that covers an approved drug. When possible, depending upon the length of clinical trials and other factors involved in the filing of a BLA, we expect to apply for patent term extensions for patents covering our product candidates and their methods of use.

17