Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EX-32.2 - EX-32.2 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex322_1115.htm |

| EX-32.1 - EX-32.1 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex321_1114.htm |

| EX-31.2 - EX-31.2 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex312_1117.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EX-31.1 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex311_1116.htm |

| EX-23.1 - EX-23.1 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex231_788.htm |

| EX-21.1 - EX-21.1 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex211_789.htm |

| EX-10.14 - EX-10.14 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex1014_281.htm |

| EX-10.11 - EX-10.11 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex1011_1877.htm |

| EX-10.9 - EX-10.9 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex109_787.htm |

| EX-10.6 - EX-10.6 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex106_280.htm |

| EX-10.5 - EX-10.5 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex105_279.htm |

| EX-10.1 - EX-10.1 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex101_786.htm |

| EX-4.5 - EX-4.5 - PRECISION BIOSCIENCES INC | dtil-ex45_1557.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K

(Mark One)

|

☒ |

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020

OR

|

☐ |

TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to |

Commission File Number 001-38841

Precision BioSciences, Inc.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

|

Delaware |

20-4206017 |

|

(State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) |

(I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

|

|

|

|

302 East Pettigrew St., Suite A-100 Durham, North Carolina |

27701 |

|

(Address of principal executive offices) |

(Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (919) 314-5512

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

|

Title of each class |

|

Trading Symbol(s) |

|

Name of each exchange on which registered |

|

|

DTIL |

|

The Nasdaq Global Select Market |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit such files). Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

|

Large accelerated filer |

|

☐ |

|

Accelerated filer |

|

☐ |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Non-accelerated filer |

|

☒ |

|

Smaller reporting company |

|

☒ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emerging growth company |

|

☒ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. YES ☐ NO ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

The aggregate market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates of the Registrant, based on the closing price of the shares of common stock on The Nasdaq Global Select Market on June 30, 2020, was $382.8 million.

The number of shares of Registrant’s common stock outstanding as of March 2, 2021 was 56,986,188.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

None.

Table of Contents

|

|

|

Page |

|

|

|

|

|

Item 1. |

1 |

|

|

Item 1A. |

46 |

|

|

Item 1B. |

97 |

|

|

Item 2. |

97 |

|

|

Item 3. |

97 |

|

|

Item 4. |

97 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 5. |

98 |

|

|

Item 6. |

98 |

|

|

Item 7. |

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations |

99 |

|

Item 7A. |

115 |

|

|

Item 8. |

116 |

|

|

Item 9. |

Changes in and Disagreements with Accountants on Accounting and Financial Disclosure |

116 |

|

Item 9A. |

116 |

|

|

Item 9B. |

116 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 10. |

117 |

|

|

Item 11. |

117 |

|

|

Item 12. |

Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters |

117 |

|

Item 13. |

Certain Relationships and Related Transactions, and Director Independence |

117 |

|

Item 14. |

117 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 15. |

118 |

|

|

Item 16 |

121 |

i

This Annual Report on Form 10-K contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. We intend such forward-looking statements to be covered by the safe harbor provisions for forward-looking statements contained in Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”) and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”). All statements other than statements of present and historical facts contained in this Annual Report on Form 10-K, including without limitation, statements regarding our future results of operations and financial position, business strategy and approach, including related results, prospective products, planned preclinical or greenhouse studies and clinical or field trials, the status and results of our preclinical and clinical studies, expected release of interim data, expectations regarding our allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor T cell immunotherapy product candidates, expectations regarding the use and effects of ARCUS, including in connection with in vivo genome editing, potential new partnerships or alternative opportunities for our product candidates, capabilities of our manufacturing facility, regulatory approvals, research and development costs, timing, expected results and likelihood of success, plans and objectives of management for future operations, as well as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic may be forward-looking statements. Without limiting the foregoing, in some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by terms such as “aim,” “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “exploring,” “plan,” “anticipate,” “could,” “intend,” “target,” “project,” “contemplate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential,” “seeks,” or “continue” or the negative of these terms or other similar expressions, although not all forward-looking statements contain these words. No forward-looking statement is a guarantee of future results, performance, or achievements, and one should avoid placing undue reliance on such statements.

Forward-looking statements are based on our management’s beliefs and assumptions and on information currently available to us. Such beliefs and assumptions may or may not prove to be correct. Additionally, such forward-looking statements are subject to a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and assumptions, and actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied in the forward-looking statements due to various factors, including, but not limited to, those identified in Part I. Item 1A. “Risk Factors” and Part II. Item 7. “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations.” These risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to:

|

|

• |

our ability to become profitable; |

|

|

• |

our ability to procure sufficient funding and requirements under our current debt instruments and effects of restrictions thereunder; |

|

|

• |

risks associated with raising additional capital; |

|

|

• |

our operating expenses and our ability to predict what those expenses will be; |

|

|

• |

our limited operating history; |

|

|

• |

the success of our programs and product candidates in which we expend our resources; |

|

|

• |

our dependence on our ARCUS technology; |

|

|

• |

the risk that other genome-editing technologies may provide significant advantages over our ARCUS technology; |

|

|

• |

the initiation, cost, timing, progress, achievement of milestones and results of research and development activities, preclinical or greenhouse studies and clinical or field trials; |

|

|

• |

public perception about genome editing technology and its applications; |

|

|

• |

competition in the genome editing, biopharmaceutical, biotechnology and agricultural biotechnology fields; |

|

|

• |

our or our collaborators’ ability to identify, develop and commercialize product candidates; |

|

|

• |

pending and potential liability lawsuits and penalties against us or our collaborators related to our technology and our product candidates; |

|

|

• |

the U.S. and foreign regulatory landscape applicable to our and our collaborators’ development of product candidates; |

|

|

• |

our or our collaborators’ ability to obtain and maintain regulatory approval of our product candidates, and any related restrictions, limitations and/or warnings in the label of an approved product candidate; |

|

|

• |

our or our collaborators’ ability to advance product candidates into, and successfully design, implement and complete, clinical or field trials; |

|

|

• |

potential manufacturing problems associated with the development or commercialization of any of our product candidates; |

|

|

• |

our ability to obtain an adequate supply of T cells from qualified donors; |

ii

|

|

|

|

• |

our ability to achieve our anticipated operating efficiencies at our manufacturing facility; |

|

|

• |

delays or difficulties in our and our collaborators’ ability to enroll patients; |

|

|

• |

changes in interim “top-line” data that we announce or publish; |

|

|

• |

if our product candidates do not work as intended or cause undesirable side effects; |

|

|

• |

risks associated with applicable healthcare, data privacy and security regulations and our compliance therewith; |

|

|

• |

the rate and degree of market acceptance of any of our product candidates; |

|

|

• |

the success of our existing collaboration agreements, and our ability to enter into new collaboration arrangements; |

|

|

• |

our current and future relationships with third parties including suppliers and manufacturers; |

|

|

• |

our ability to obtain and maintain intellectual property protection for our technology and any of our product candidates; |

|

|

• |

potential litigation relating to infringement or misappropriation of intellectual property rights; |

|

|

• |

market and economic conditions; |

|

|

• |

effects of system failures and security breaches; |

|

|

• |

effects of natural and manmade disasters, public health emergencies and other natural catastrophic events; |

|

|

• |

effects of COVID-19, or any pandemic, epidemic, or outbreak of an infectious disease; |

|

|

• |

insurance expenses and exposure to uninsured liabilities; |

|

|

• |

effects of tax rules; and |

|

|

• |

risks related to ownership of our common stock, including fluctuations in our stock price. |

Moreover, we operate in an evolving environment. New risk factors and uncertainties may emerge from time to time, and it is not possible for management to predict all risk factors and uncertainties.

You should read this Annual Report on Form 10-K and the documents that we reference herein completely and with the understanding that our actual future results may be materially different from what we expect. We qualify all of our forward-looking statements by these cautionary statements. All forward-looking statements contained herein speak only as of the date of this Annual Report on Form 10-K. Except as required by applicable law, we do not plan to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statements contained herein, whether as a result of any new information, future events, changed circumstances or otherwise.

As used in this Annual Report on Form 10-K, unless otherwise stated or the context requires otherwise, references to “Precision,” the “Company,” “we,” “us,” and “our,” refer to Precision BioSciences, Inc. and its subsidiaries on a consolidated basis.

iii

Our business is subject to numerous risks and uncertainties, including those described in Part I. Item 1A. “Risk Factors” in this Annual Report on Form 10-K. You should carefully consider these risks and uncertainties when investing in our common stock. Some of the principal risks and uncertainties include the following.

|

|

• |

We have incurred significant operating losses since our inception and expect to continue to incur losses for the foreseeable future. We have never been profitable, and may never achieve or maintain profitability. |

|

|

• |

We will need substantial additional funding, and if we are unable to raise a sufficient amount of capital when needed on acceptable terms, or at all, we may be forced to delay, reduce or eliminate some or all of our research programs, product development activities and commercialization efforts. |

|

|

• |

We have a limited operating history, which makes it difficult to evaluate our current business and future prospects and may increase the risk of your investment. |

|

|

• |

ARCUS is a novel technology, making it difficult to predict the time, cost and potential success of product candidate development. We have not yet been able to assess the safety and efficacy of most of our product candidates in humans, and have only limited safety and efficacy information in humans to date regarding one of our product candidates. |

|

|

• |

We are heavily dependent on the successful development and translation of ARCUS, and due to the early stages of our product development operations, we cannot give any assurance that any product candidates will be successfully developed and commercialized. |

|

|

• |

Adverse public perception of genome editing may negatively impact the developmental progress or commercial success of products that we develop alone or with collaborators. |

|

|

• |

We face significant competition in industries experiencing rapid technological change, and there is a possibility that our competitors may achieve regulatory approval before us or develop product candidates or treatments that are safer or more effective than ours, which may harm our financial condition and our ability to successfully market or commercialize any of our product candidates. |

|

|

• |

Our future profitability, if any, depends in part on our and our collaborators’ ability to penetrate global markets, where we would be subject to additional regulatory burdens and other risks and uncertainties associated with international operations that could materially adversely affect our business. |

|

|

• |

Product liability lawsuits against us could cause us to incur substantial liabilities and could limit commercialization of any products that we develop alone or with collaborators. |

|

|

• |

The regulatory landscape that will apply to development of therapeutic product candidates by us or our collaborators is rigorous, complex, uncertain and subject to change, which could result in delays or termination of development of such product candidates or unexpected costs in obtaining regulatory approvals. |

|

|

• |

Clinical trials are difficult to design and implement, expensive, time-consuming and involve an uncertain outcome, and the inability to successfully and timely conduct clinical trials and obtain regulatory approval for our product candidates would substantially harm our business. |

|

|

• |

Even if we obtain regulatory approval for any products that we develop alone or with collaborators, such products will remain subject to ongoing regulatory requirements, which may result in significant additional expense. |

|

|

• |

Even if any product we develop alone or with collaborators receives marketing approval, such product may fail to achieve the degree of market acceptance by physicians, patients, healthcare payors and others in the medical community necessary for commercial success. |

|

|

• |

The ongoing novel coronavirus disease, COVID-19 has impacted our business and any other pandemic, epidemic or outbreak of an infectious disease may materially and adversely impact our business, including our preclinical studies and clinical trials. |

iv

We are a life sciences company dedicated to improving life through the application of our pioneering, proprietary ARCUS genome editing platform. We leverage ARCUS in the development of our product candidates, which are designed to treat human diseases and create healthy and sustainable food and agricultural solutions. We are actively developing product candidates in three innovative areas: allogeneic CAR T cell immunotherapy, in vivo gene correction, and food. We are currently conducting a Phase 1/2a clinical trial of PBCAR0191 in adult patients with relapsed or refractory, or R/R, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or NHL, or R/R B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or B-ALL. PBCAR0191 is our first gene-edited allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, T cell therapy candidate targeting CD19 and is being developed in collaboration with Les Laboratoires Servier, or Servier, pursuant to a development and commercial license agreement, as amended (the “Servier Agreement”). We have received orphan drug designation, for PBCAR0191 from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”), for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL. In August 2020, the FDA granted Fast Track Designation for PBCAR0191 for the treatment of B-ALL. The NHL cohort will include patients with mantle cell lymphoma (“MCL”), an aggressive subtype of NHL, for which we have received orphan drug designation from the FDA. Made from donor-derived T cells modified using our ARCUS genome editing technology, PBCAR0191 recognizes the well characterized tumor cell surface protein CD19, an important and validated target in several B-cell cancers, and is designed to avoid graft-versus-host disease, or GvHD, a significant complication associated with donor-derived, cell-based therapies. We believe that this trial, which is designed to assess the safety and tolerability of PBCAR0191 at increasing dose levels, as well as to evaluate anti-tumor activity, is the first U.S.-based clinical trial to evaluate an allogeneic CAR T therapy for R/R NHL. Furthermore, we believe that our proprietary, one-step engineering process for producing allogeneic CAR T cells with a potentially optimized cell phenotype, at large scale in a cost-effective manner, will enable us to overcome the fundamental clinical and manufacturing challenges that have limited the CAR T field to date. We expect to report updated interim data for the PBCAR0191 study in mid-year 2021.

In April 2020, we commenced patient dosing in a Phase 1/2a clinical trial with our second allogeneic CAR T cell therapy product candidate, PBCAR20A. PBCAR20A is wholly owned by us and targets the validated tumor cell surface target CD20. It is being investigated in R/R NHL, including those with R/R chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL, or R/R small lymphocytic lymphoma, or SLL. A subset of the NHL patients will have the diagnosis of MCL and we have received orphan drug designation for PBCAR20A from the FDA for the treatment of this disease. Based on the safety profile observed to date with PBCAR0191, the FDA allowed us to commence dosing with PBCAR20A directly at 1 x 106 cells/kg. The study has continued to escalate through dose level two (3 x 106 cells/kg), and, in February 2021, we commenced patient dosing at dose level 3 (480 x 106 cell fixed dose) with a max dose of 6 x 106 cells/kg. We expect to report interim data for the PBCAR20A study in 2021.

In June 2020, we commenced patient dosing in a Phase 1/2a clinical trial with our third allogenic CAR T cell therapy product candidate, PBCAR269A. The starting dose of PBCAR269A is 6 x 105 cells/kg. PBCAR269A is wholly owned by us and is designed to target the validated tumor cell surface target BCMA. It is being investigated in subjects with R/R multiple myeloma and we have received orphan drug designation and Fast Track Designation from the FDA for this indication. In September 2020, we announced that we entered into a clinical trial collaboration with SpringWorks Therapeutics, Inc. (“SpringWorks”), a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on developing medicines for patients with severe rare diseases and cancer. Pursuant to the collaboration, PBCAR269A will be evaluated in combination with nirogacestat, SpringWorks’ investigational gamma secretase inhibitor (“GSI”), in patients with R/R multiple myeloma, which is expected to commence in the first half of 2021. In February 2021, we commenced patient dosing at the highest dose cohort, dose level 3 of 6 x 106 cells/kg and we expect to report interim data on the PBCAR269A trial in 2021.

Additionally, in June 2020, Elo Life Systems (“Elo”), our wholly-owned subsidiary, established a strategic partnership with the Dole Food Company (“Dole”) and entered into a Research, Development, and Commercialization Agreement with Dole, with the aim to co-develop banana varieties resistant to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp cubense Tropical race 4 (“Foc TR4”), utilizing proprietary computational biology workflows and the ARCUS genome editing platform. The disease caused by Foc TR4, commonly known as Fusarium wilt, threatens the continued cultivation of the world’s most popular variety of banana called Cavendish, which is of considerable economic significance as this variety is used to produce export bananas for key markets around the globe and Dole is one of the largest producers in the industry. Fungicides, or other traditional means of disease control have failed as the pandemic continues to spread across vital banana growing economies.

In September 2020, we regained full clinical development and commercialization rights, and all data we generated for the in vivo chronic hepatitis B virus (“HBV”) program developed under our 2018 collaboration agreement with Gilead Sciences. We are exploring partnership or alternative opportunities to enable the continued development of ARCUS-based HBV therapies.

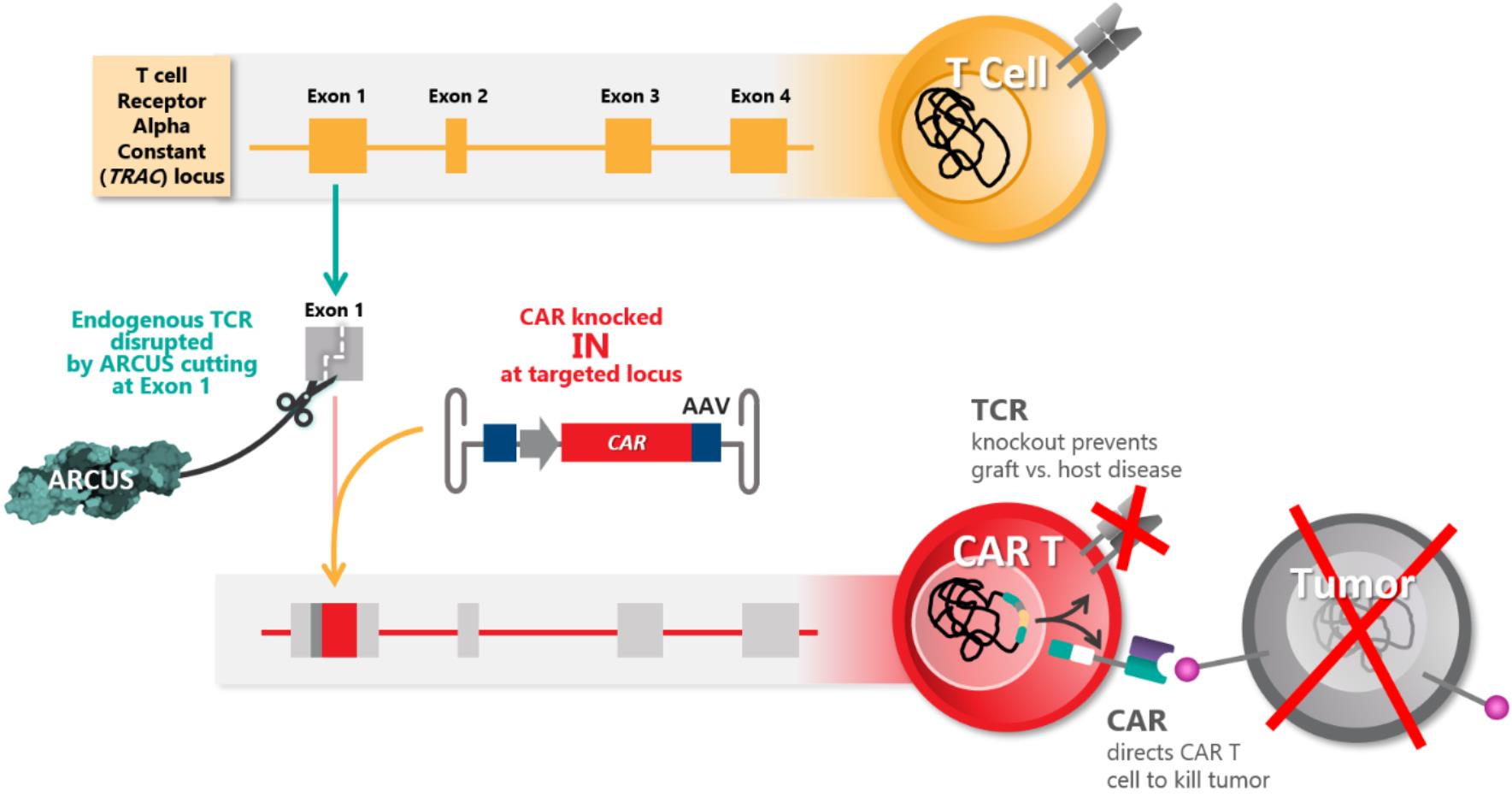

In October 2020, we announced the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) issued judgements in our favor in two patent interference proceedings that challenged nine U.S. patents we owned. The patents, which issued in 2018, relate to allogeneic CAR T cells produced by inserting a gene encoding a CAR into the T cell receptor (“TCR”) alpha chain (“TRAC”)

1

locus, as well as methods of using those cells for cancer immunotherapy. In the interference proceedings, a third party argued that it had invented the technology in 2012. The PTAB, however, found that the third-party patent application did not satisfy the written description requirement and rejected these claims while maintaining the claims in all nine of our patents.

In November 2020, we announced a research collaboration and exclusive license agreement with Eli Lilly and Company (“Lilly”) to utilize ARCUS for the research and development of potential in vivo therapies for genetic disorders, with an initial focus on Duchenne muscular dystrophy (“DMD”) and two other undisclosed gene targets. Under the agreement, Lilly has the right to nominate up to three additional gene targets for genetic disorders over the first four years of the Development and License Agreement, which may be extended to six years upon Lilly’s election and payment of an extension fee.

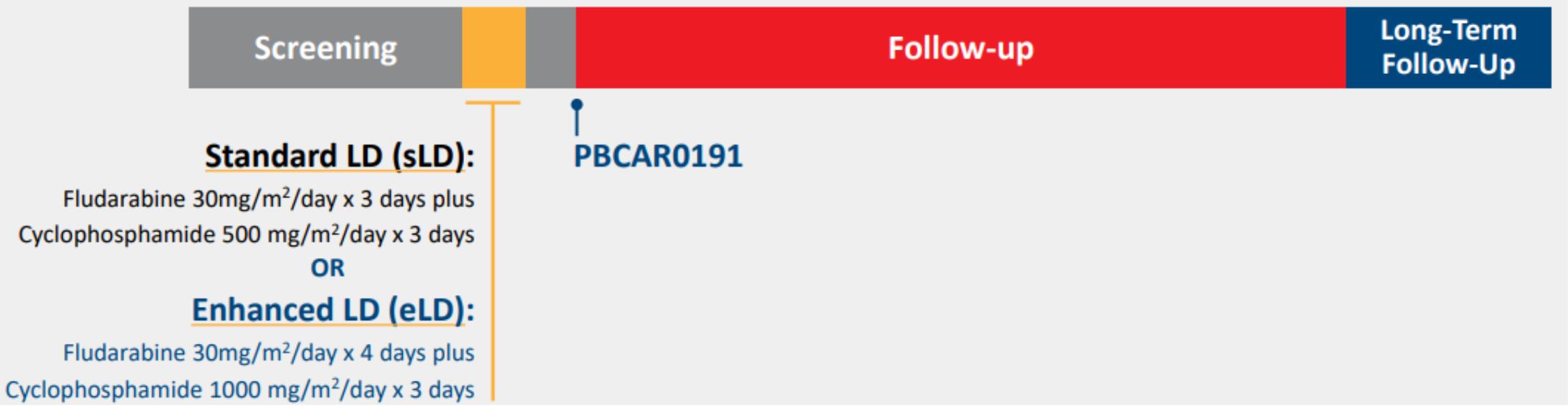

In December 2020, we announced interim clinical results from our Phase 1/2a study of PBCAR0191 as a treatment of R/R NHL and R/R B-ALL. As of the November 16, 2020 cutoff, 27 patients including 16 patients with aggressive NHL and 11 patients with aggressive B-ALL were enrolled and evaluated. In this dose escalation and dose expansion study, PBCAR0191 had an acceptable safety profile with no cases of graft versus host disease, no cases of Grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome, and no cases of Grade ≥ 3 neurotoxicity. PBCAR0191 demonstrated longest durability of response to 11 months in B-ALL. PBCAR0191 with enhanced lymphodepletion (“eLD”) resulted in objective response rate of 83% (5/6) in NHL and B-ALL as compared to 33% (3/9) in NHL with standard lymphodepletion (“sLD”).

Additionally, in December 2020, researchers at Elo in collaboration with Alan Chambers, Ph.D., and the Tropical Research and Education Center at the University of Florida published a paper in Nature Food, reporting a chromosome-scale, phased Vanilla planifolia genome, which revealed sequence variants for genes that may impact the vanillin pathway, and therefore influence bean quality, including its productivity, flower anatomy, and disease resistance.

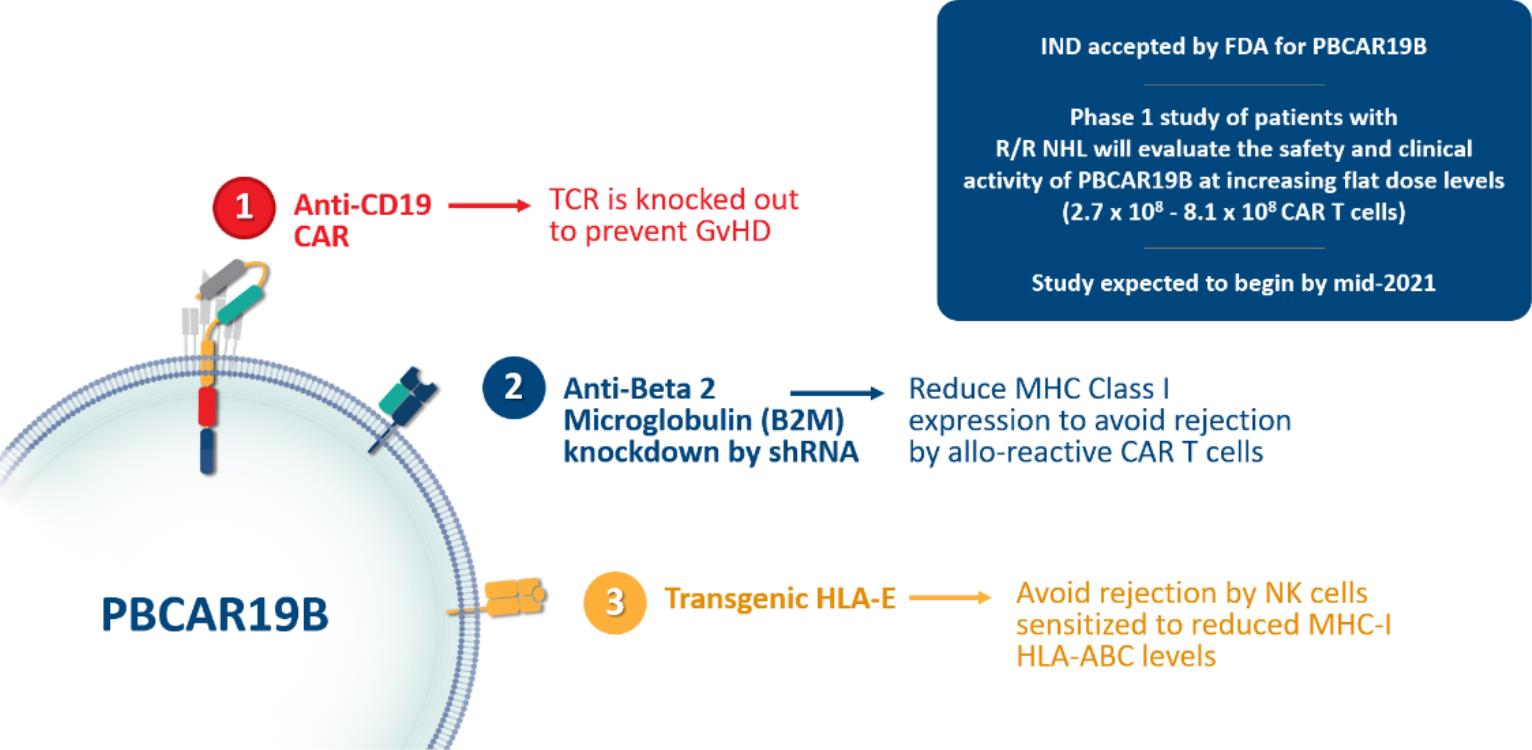

In January 2021, we announced that the FDA has accepted our Initial New Drug (“IND”) application for PBCAR19B, our next-generation, stealth cell, CD19 allogenic CAR T candidate for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and we expect to begin the Phase 1 study by mid-2021. Additionally, in January 2021, we announced that we received a Notice of Allowance from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for a patent application covering PBCAR19B. The allowed composition claims of this patent application encompass genetically-modified human T cells comprising the PBCAR19B construct, which is inserted within the T cell receptor alpha constant locus. Once issued, patents arising from this patent family will have standard expiration dates in April 2040. In preclinical studies, PBCAR19B has shown to delay both T cell and natural killer cell mediated allogeneic rejection in vitro and may improve the persistence of allogeneic CAR T cells.

We expect to advance a program targeting the rare genetic disease primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (“PH1”) as our lead wholly owned in vivo gene correction program. PH1 affects approximately 1-3 people per million in the United States and is caused by loss of function mutations in the AGXT gene, leading to the accumulation of calcium oxalate crystals in the kidneys. Patients suffer from painful kidney stones which may ultimately lead to renal failure. Using ARCUS, we are developing a potential therapeutic approach to PH1 that involves knocking out a gene called HAO1 which acts upstream of AGXT. Suppressing HAO1 has been shown in preclinical models by us to prevent the formation of calcium oxalate. We therefore believe that a one-time administration of an ARCUS nuclease targeting HAO1 may be a viable strategy for a durable treatment of PH1 patients. Pre-clinical research has continued to progress, and we expect to provide an update on this program in the first half of 2021.

In January 2021, we disclosed our intention to spinout our wholly owned subsidiary, Elo. We are continuing to explore our strategic options, and the timing of any such sale, spinout or other treatment of Elo remains uncertain.

Our Pipeline

Allogeneic CAR T Immunotherapy

We believe that we have developed a transformative allogeneic CAR T immunotherapy platform with the potential to overcome certain limitations of autologous CAR T cell therapies and significantly increase patient access to these cutting‑edge treatments. Cancer immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses the body’s immune system to fight the disease. CAR T is a form of immunotherapy in which a specific type of immune cell, called a “T cell”, is genetically engineered to recognize and kill cancer cells. Current commercially available CAR T therapies are autologous, meaning the T cells used as the starting material for this engineering process are derived directly from the patient. As a consequence, the therapy is highly personalized, difficult to scale, and expensive. Our allogeneic approach uses donor‑derived T cells that are gene edited using ARCUS and are designed for safe delivery to an unrelated patient. We believe that this donor-derived approach will allow us to consistently produce a potent product by selecting donors with high quality T cells and will lessen the product-to-product variability seen in autologous therapies. We are able to produce allogeneic CAR T cells at a large scale in a cost-effective manner and have the potential to overcome the “one patient: one product” burden of autologous CAR T cell therapies.

2

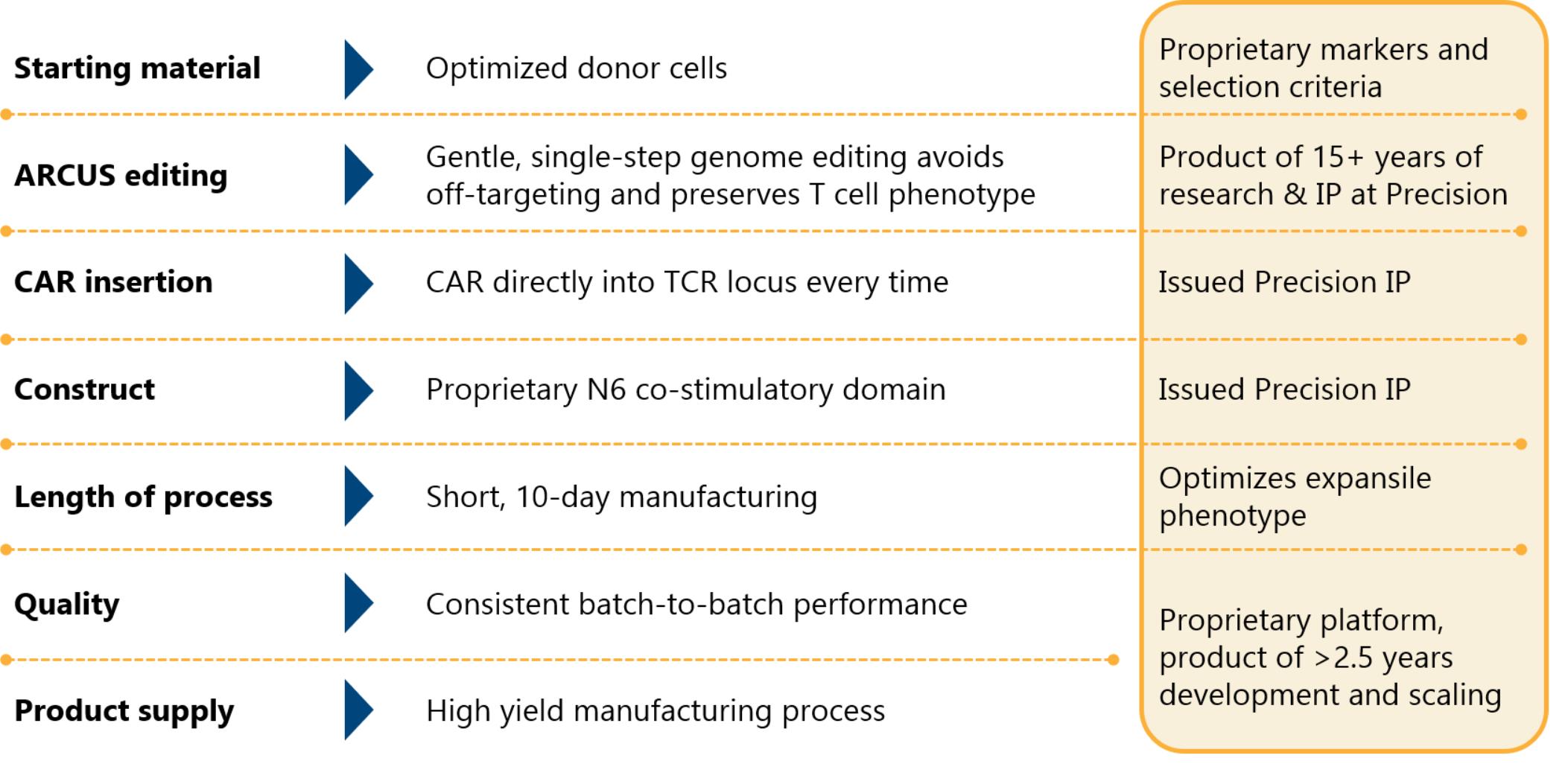

Leveraging the unique gene editing capabilities of ARCUS, we have developed a one-step cell engineering process for allogeneic CAR T cells that is designed to maintain naïve and central memory T cell phenotypes throughout the CAR T manufacturing process, which we believe to be important for an optimized CAR T therapy. Due to our one-step editing method and the decision early in the development of our allogeneic CAR T immunotherapy platform to invest in process development, we have scaled our manufacturing process and are currently producing allogeneic CAR T cells at large scale in accordance with current good manufacturing practice, or cGMP.

In February 2016, we entered into the Servier Agreement. Pursuant to this agreement we have agreed to perform early-stage research and development on individual T cell modifications for five unique antigen targets. Servier selected one target at the Servier Agreement’s inception and, during 2020, selected two additional hematological cancer targets beyond CD19 and two new solid tumor targets. With the addition of these new targets, we received development milestone payments in 2020 and may be eligible to receive additional development milestone payments in 2021. Upon selection of an antigen target, we have agreed to develop the resulting therapeutic product candidates through Phase 1 clinical trials and prepare the clinical supply of such product candidates for use in Phase 2 clinical trials. We have the ability to opt-in to a 50/50 co‑development and co-promotion agreement in the United States on all licensed products under the Servier Agreement.

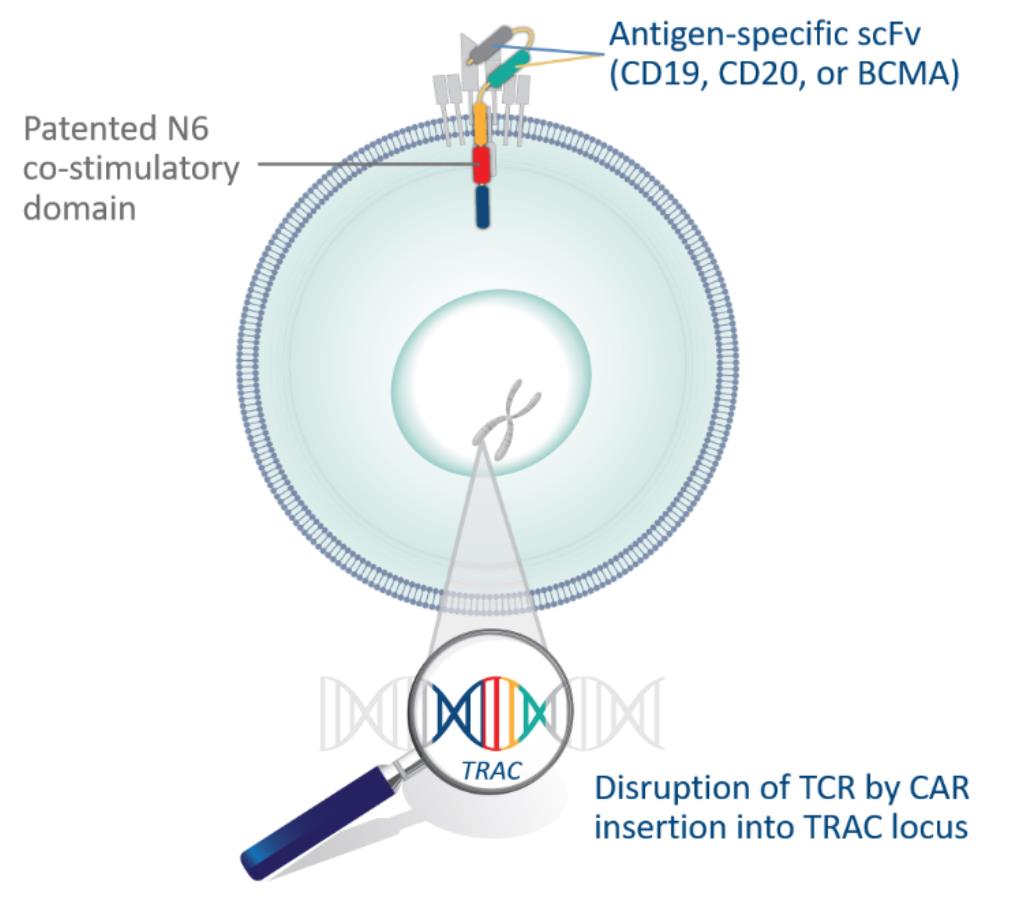

Our most advanced program, PBCAR0191, is an allogeneic CAR T cell therapy candidate targeting the well-validated tumor target CD19 and is being developed for the treatment of adult patients with NHL and B-ALL. CD19 is a protein that is expressed on the surface of B cells. The FDA has granted PBCAR0191 orphan drug designation for the treatment of ALL and, in August 2020 granted PBCAR0191 Fast Track Designation for treatment of B-ALL.

We reported updated interim data from our ongoing Phase 1/2a clinical trial of PBCAR0191 including response rates across R/R NHL and R/R B-ALL patient cohorts as further described in “Our Allogeneic CAR T Immunotherapy Pipeline.”

PBCAR0191, which incorporates our patented N6 co-stimulatory domain, demonstrated a clear dose dependent increase in peak cell expansion. Compared to sLD, eLD with PBCAR0191 at DL3 resulted in approximately 95-fold increase in peak cell expansion, and approximately 45-fold increase in area under the curve. This was associated with a higher CR rate in NHL (75%).

In this dose escalation and dose expansion study, PBCAR0191 had an acceptable safety profile with no cases of graft versus host disease, no cases of Grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome, and no cases of Grade ≥ 3 immune effector cell neurotoxicity.

One NHL patient who was treated with PBCAR0191 and eLD had previously received nine prior lines of therapy before entering the trial. The patient presented with persistent cytopenias at baseline and a history of infections, including bacterial sepsis. The patient had an episode of sepsis at day 27 which appeared to have resolved at day 33, following which a partial response was achieved at day 34. Unfortunately, the patient died at day 42 with grade 5 sepsis. We reported the serious adverse event to the FDA and reported the patient death.

We are enrolling additional patients with eLD and plan to present updated interim data on this study by mid-2021.

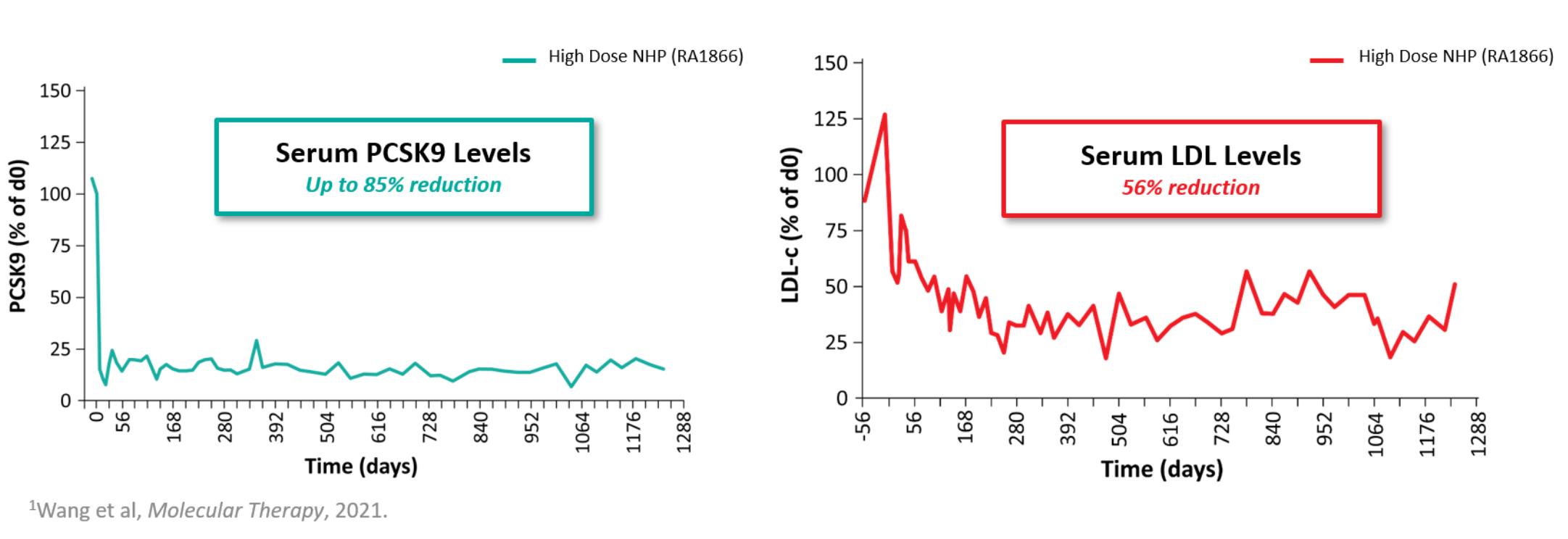

In vivo Gene Correction. Our goal is to cure genetic diseases by correcting the DNA errors responsible for causing them. In vivo gene corrections are gene corrections that take place in a living organism. We have advanced a deep portfolio of diverse programs toward preclinical efficacy and toxicity studies. We have generated a significant large animal dataset that we believe to be the most comprehensive of any in the field and have observed high-efficiency in vivo genome editing in non-human primates (“NHPs”) in our preclinical studies, as highlighted in our July 2018 publication in Nature Biotechnology. We believe this is the first peer-reviewed publication of in vivo genome editing data in NHPs. In our preclinical studies, we observed the high-efficiency editing of the PCSK9 gene in NHPs using ARCUS and, even at the highest dose, the treatment was observed to be well-tolerated. As published in Molecular Therapy in February 2021, the NHPs have been monitored for more than three years and have continued to show a sustained reduction in low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels while maintaining stable gene editing without any obvious adverse effects. After the one-time vector administration more than three years ago, NHPs treated with ARCUS have experienced stable reductions of up to 85% in PCSK9 protein levels and a 56% reduction of low-density lipoprotein (“LDL”) cholesterol levels.

3

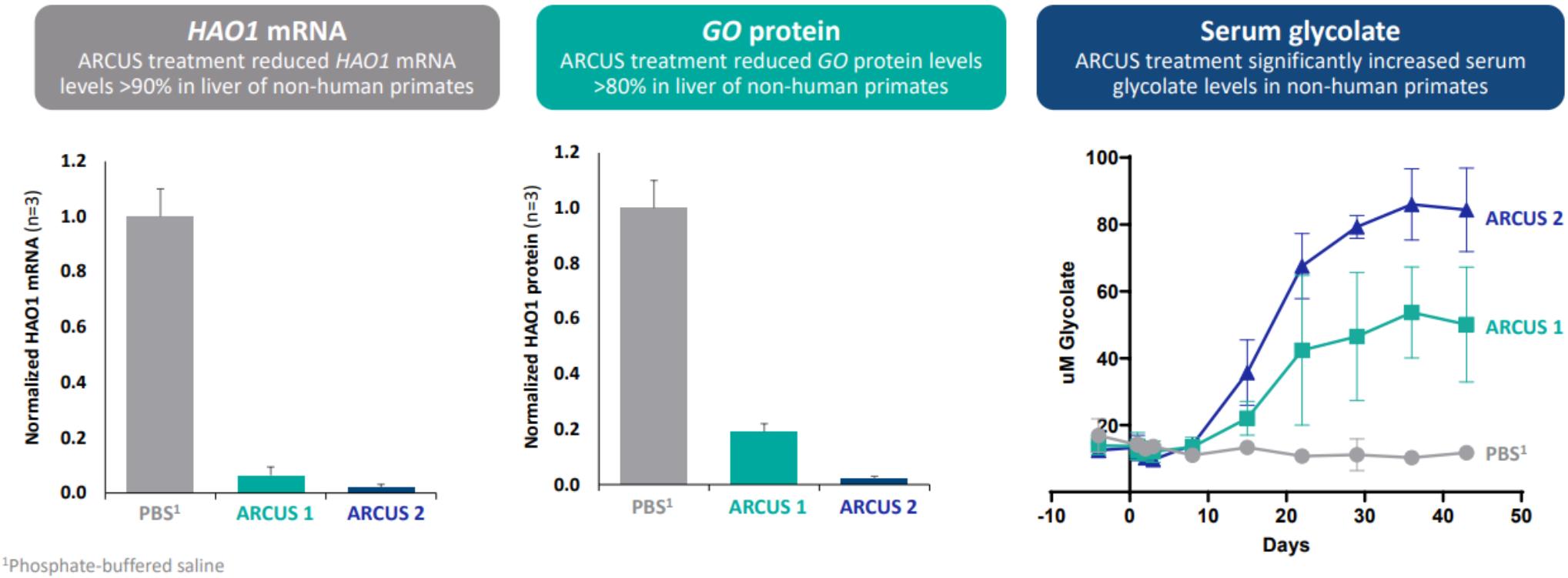

We expect to advance a program for the treatment of the rare genetic disease PH1 as our lead wholly owned gene correction program, based on preclinical data we have generated high efficiency knock out of the HAO1 target gene in NHPs using ARCUS, and evidence from a mouse model of clinically meaningful biomarker changes using our approach. We expect to provide an update on this program during the first half of 2021.

As discussed above, in November 2020, we announced a research collaboration and exclusive license agreement with Lilly, pursuant to which we will be responsible for conducting certain pre-clinical research and IND-enabling activities with respect to the gene targets nominated by Lilly. Lilly will be responsible for conducting clinical development and commercialization activities for licensed products resulting from the collaboration and may engage with us for additional clinical and/or initial commercial manufacture of licensed products.

We expect to advance a program for the treatment of the rare genetic disease PH1 as our lead wholly owned gene correction program, based on preclinical data we have generated high efficiency knock out of the HAO1 target gene in NHPs using ARCUS, and evidence from a mouse model of clinically meaningful biomarker changes using our approach. We expect to provide an update on this program during the first half of 2021.

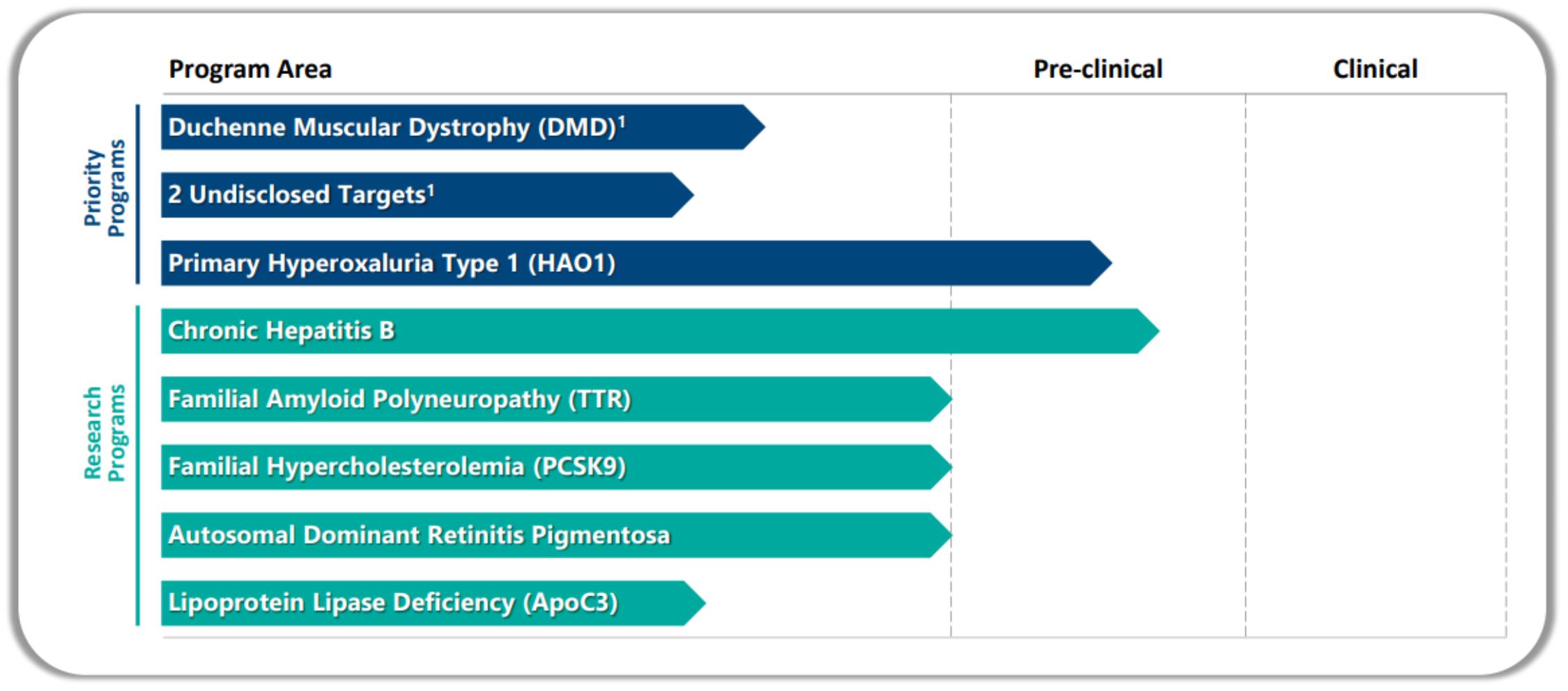

We are also in the discovery stage for other in vivo indications: lipoprotein lipase deficiency, familial amyloid polyneuropathy, familial hypercholesterolemia, and autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa.

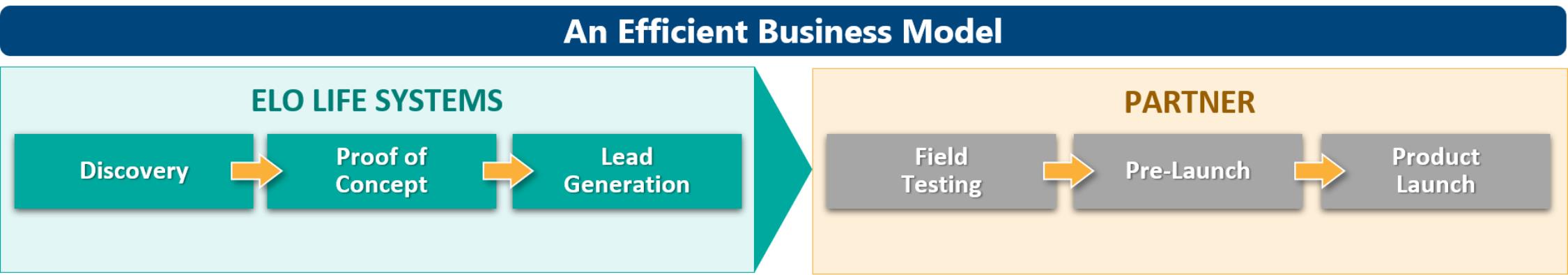

Food. Our food platform, which we operate through our wholly owned subsidiary, Elo, is an integrated suite of gene discovery and crop engineering technologies that is designed to generate products in collaboration with leading food producers. Elo has a team with in-depth experience in crop genome editing. Over the last decade, Elo has worked with some of the largest plant biotechnology companies to edit gene targets and develop potential product candidates in a variety of crop plants. By combining the power of the ARCUS technology platform with target discovery, transformation and high throughput trait evaluation, Elo has enabling our partners to potentially address critical issues in food and agriculture created by climate change and dramatic shifts in consumer preference toward healthier eating. Elo’s collaboration-driven business model enables Elo to remain capital efficient throughout the product development cycle while generating revenue through various revenue-sharing models. Elo achieved proof of concept with its ZeroMelonTM watermelon-based sweetener program and advanced the program to greenhouse trials. This program is intended to leverage ARCUS to develop a scalable low-calorie sweetener. As discussed above, Elo also entered into a Research, Development, and Commercialization Agreement with Dole. with the aim to co-develop banana varieties resistant to FOC TR4, utilizing proprietary computational biology workflows and the ARCUS genome editing platform. Elo’s ClimateSmart Chickpea program addresses the effect of climate change as a foundational trait for the plant-based protein industry. Edited chickpea plants were successfully created at a subsidiary of Elo in Australia in collaboration with the Queensland University of Technology. Genotypic and phenotypic screens are in progress.

Our Team

We believe that our team, whom we call Precisioneers, has among the deepest scientific experience and capabilities of all genome editing companies. Derek Jantz, Ph.D., our Chief Scientific Officer and a co-founder of Precision, and Jeff Smith, Ph.D., our Chief Technology Officer and also a co-founder of Precision, have been working with genome editing technology for more than 15 years. They are pioneers in the genome editing field and developed the ARCUS genome editing platform to address what they perceived as limitations in the existing genome editing technologies. Our Chief Executive Officer, Matthew Kane, also a co-founder of Precision, has almost 20 years’ experience in life sciences, most of which has been working in genome editing.

We have selectively expanded our team of Precisioneers to include individuals with extensive industry experience and expertise in the discovery, development and manufacture of cell and gene therapies and the creation of innovative solutions to myriad problems affecting food systems. As of December 31, 2020, our team of Precisioneers included more than 57 scientists with Ph.D. degrees.

We are a purpose-driven organization, and we have carefully promoted a culture that values innovation, accountability, respect, adaptability and perseverance. We strive to ensure that our open, collaborative culture empowers Precisioneers to be their best selves and do their best work. We strongly believe that our shared values will help our team navigate and overcome challenges we may experience as we pursue our mission of improving life through genome editing. Our culture has helped build a world-class team with industry-leading experience in genome editing and continually attracts new talent to further build our capabilities. Our team is a group of motivated individuals that value the opportunity to contribute their time and talents toward the pursuit of improving life. Precisioneers appreciate high-quality research and are moved by the opportunity to translate their work into treatments and solutions that will impact human health.

4

Our Strategy

We are dedicated to improving life. Our goal is to broadly translate the potential of genome editing into permanent genetic solutions for significant unmet needs. Our strategy to achieve this goal includes the following key elements:

|

|

• |

Create a fully integrated genome editing company capable of delivering solutions that address unmet needs impacting human health. We believe that to be a leader in the field of genome editing and maximize the impact of our ARCUS genome editing platform, we must be able to control those elements of our business that may provide us with certain strategic advantages or operational efficiencies. We intend to continue to invest in comprehensive research, development, manufacturing and commercial capabilities that provide control and oversight of our product candidates from discovery through commercialization. |

|

|

• |

Capitalize on our emerging leadership position in allogeneic CAR T immunotherapies. We believe that we have developed the first allogeneic CAR T cell platform capable of producing drug product at scale, with a potentially optimal cell profile for therapeutic efficacy and true off-the-shelf delivery without the need for harsh and potentially toxic lymphodepletion. We have selected three validated CAR T cell targets that we believe offer the greatest chance of clinical success for our initial product candidates. Our CAR T platform is modular, which we believe will allow us to leverage proof-of-concept from our ongoing and planned initial human trials for multiple other CAR T programs. We believe the combination of these factors, along with our unique ARCUS technology, puts us in a differentiated position to be the leader in the development of allogeneic CAR T therapies. |

|

|

• |

Advance ARCUS-based in vivo gene correction programs into human clinical trials. In our preclinical studies, we observed the high-efficiency and tolerability of in vivo genome editing using ARCUS in a non-human primate model, as published in Nature Biotechnology in July 2018 and Molecular Therapy in February 2021. To our knowledge, we are the first company to complete this milestone, which we believe to be critical to successful in vivo genome editing therapeutic development. We have built on this early success by diligently advancing a diverse portfolio of preclinical in vivo gene correction programs through additional large animal studies, focusing initially on gene targets occurring in the liver and eye. As discussed above, in November 2020, we also announced a research collaboration and exclusive license agreement with Lilly to utilize ARCUS for the research and development of potential in vivo therapies for genetic disorders, with an initial focus on DMD and two other undisclosed gene targets. |

|

|

• |

Continue investing in the optimization of ARCUS and enabling technologies. We believe that a key to our future success is the quality of the genome editing tools that we produce. Since our founding, we have devoted ourselves to continuously refining the precision and efficiency of our core genome editing platform. We intend to continue this investment in ARCUS while surrounding it with enabling technologies and expertise to retain what we believe is a leadership position in the field. |

|

|

• |

Create an environment that is a destination of choice for premier talent within the life sciences industry. We believe that we currently have among the deepest and strongest skill set within the genome editing industry and credit much of our past success to our commitment to our team and culture. Our future success will depend on our ability to continue to attract and retain world-class talent within our markets of interest. We intend to consciously invest in fostering an environment within our company that is both challenging and supportive and inspires our team to broadly translate genome editing into permanent genetic solutions. |

|

|

• |

Expand the breadth of our operations through additional product platforms and strategic relationships. We believe that the ARCUS genome editing platform has broad utility beyond our current areas of focus. We intend to invest in the development of additional product platforms and seek collaborations with companies with additive expertise in areas outside of our current target markets to maximize the value of our company. |

5

Overview of Genome Editing

Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, carries the genetic instructions for all basic functions of a living cell. These instructions are encoded in four different molecules, called bases, which are strung together in specific sequences to form genes. Each gene is responsible for a specific function in a cell, and the complete set of genes in a cell, which can consist of tens of thousands of genes and billions of individual bases, is known as a genome. The complete genome sequence has been determined for many organisms, including humans. This allows scientists to identify specific genes and determine how their unique sequences contribute to a particular cellular function. Studying variations in gene sequences further informs an understanding of why a cell behaves a certain way, which can greatly enhance understanding of what causes and how to treat aberrant behavior that leads to disease.

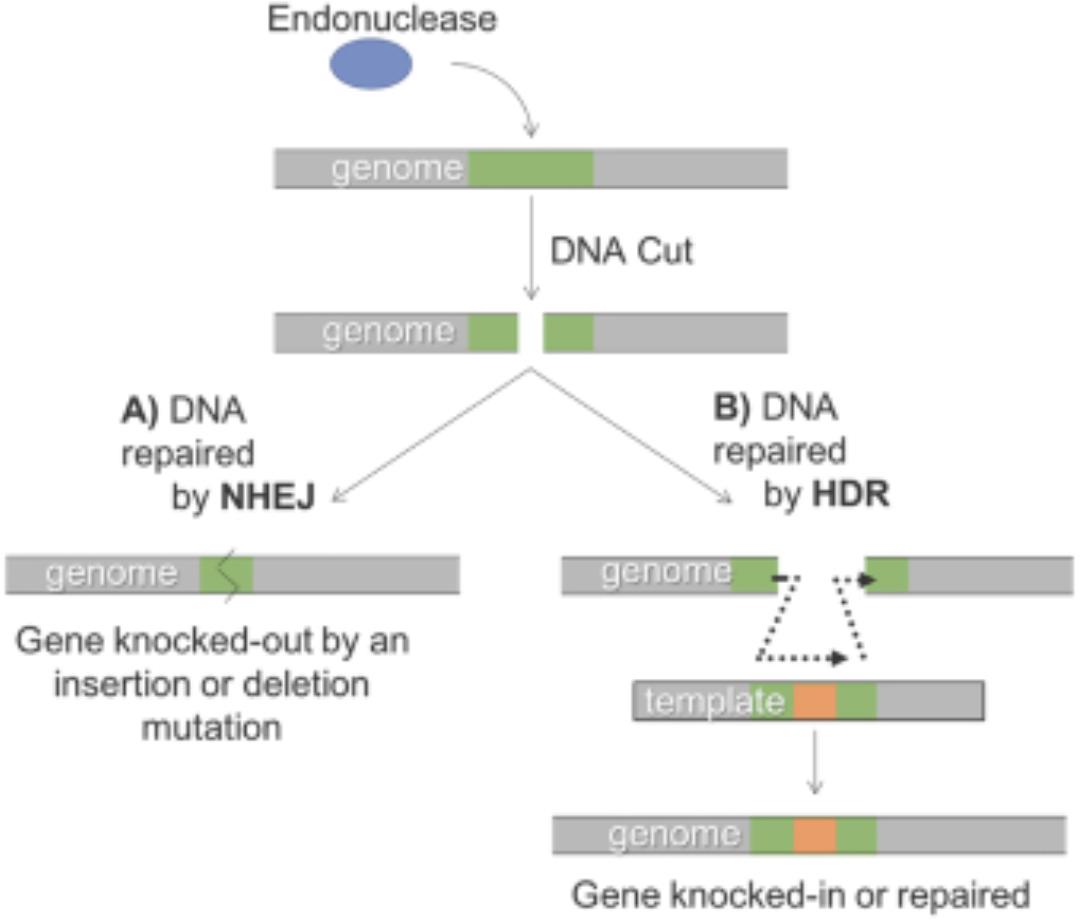

Genome editing is a biotechnology process that removes, inserts or repairs a portion of DNA at a specific location in a cell’s genome. Early applications of genome editing focused on advancing genetic research. As genome editing technologies have advanced, their application is moving beyond understanding disease to treating or preventing disease by editing DNA. Genome editing is accomplished by delivering a DNA cutting enzyme, called an endonuclease, to a targeted segment of genetic code. Once the endonuclease cuts the DNA, the cell has to repair the break to survive and will generally do so in one of two ways, as shown below.

There are two primary mechanisms of DNA repair, non-homologous end joining, or NHEJ, and homology directed repair, or HDR. As shown in A) above, NHEJ is a pathway that repairs breaks in DNA without a template. NHEJ is the less precise method of repair that prioritizes speed over accuracy, making it prone to leaving insertions and/or deletions of DNA bases at the cut site. These insertions or deletions can disrupt the gene sequence and can be used to inactivate or “knock out” the function of the gene. Accordingly, genome editing technologies can be used to permanently knock out a gene in a cell or organism by creating a break in the DNA sequence of that gene.

As shown in B) above, HDR is a mechanism of DNA repair whereby the cell uses a second DNA molecule with a sequence similar to that of the cut DNA molecule to guide the repair process. Since HDR uses a “template” of similar genetic information to guide the repair process, it is the more precise mechanism of cellular repair. HDR results in the sequence of the template being copied permanently into the genome at the site of the DNA cut. If we provide a template DNA molecule directly to the edited cell and the cell repairs itself using HDR, a new gene can be incorporated or “knocked in” at a precise location in the genome. Alternatively, the use of HDR can “repair” a DNA mutation by correcting it to the proper functioning sequence when repairing the break. Thus, genome editing endonucleases can be used to introduce a variety of different changes to the genetic code of a cell or organism including gene knockout, gene insertion and gene repair.

There are several genome editing technologies, including ARCUS, zinc-finger nucleases, or ZFNs, TAL-effector nucleases, or TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9. These technologies differ from one another principally in the properties of the endonuclease that they each employ. The different endonucleases have fundamentally different mechanisms of recognizing and cutting their DNA targets, which gives each technology advantages and disadvantages depending on how each is used.

6

Our Approach to Genome Editing

We are pioneers in the field of genome editing and have extensive experience with a breadth of genome editing technologies. Our ARCUS platform was developed to address limitations of other editing technologies that could impair their deployment for therapeutic applications. We looked to nature for examples of genome editing and found the I-CreI endonuclease from the algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Unlike ZFN, TALEN or CRISPR/Cas9, I-CreI is a natural enzyme that evolved to edit a large, complex genome. In nature, it is responsible for modifying a specific location in the algae genome by inserting a gene using the HDR process, according to scientific literature.

We believe that I-CreI has a number of attributes that make it attractive for the development of novel genome editing endonucleases, such as:

|

|

• |

Specificity. Complex genome editing applications, especially those involving the human body, require a high level of endonuclease specificity to limit the likelihood that the endonuclease will recognize and edit any genetic sequence other than its intended target. Based on scientific literature, we believe that several attributes of I-CreI naturally inhibit off-target cutting. I-CreI. |

|

|

• |

Efficiency. Most applications of genome editing technology require that a sufficient portion of the targeted cells are edited to achieve the desired result. The activity level of the endonuclease is one factor that can affect how many cells are edited. The slow catalytic mechanism of I-CreI imparts specificity but does not impact its on-target efficiency for genome editing purposes because genome editing involves cutting only a single site in a cell. As such, I-CreI is able to achieve a high level of on-target editing while rarely cutting off-target, as supported by scientific literature. |

|

|

• |

Delivery. Size and structural simplicity affect the ease with which endonucleases can be delivered to cells for editing. I-CreI is very small relative to other genome editing endonucleases. It is approximately one quarter to one sixth of the size of the ZFN, TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 endonucleases. Unlike those endonucleases, I-CreI can be delivered as a single gene. As such, we believe it is compatible with many different delivery mechanisms. Additionally, I-CreI’s size and structure facilitate the simultaneous delivery of multiple engineered endonucleases to introduce more than one edit to a cell. Both of these properties significantly broaden the spectrum of potential applications for I-CreI-based genome editing endonucleases. |

|

|

• |

Type of Cut. The three prime, or 3’, overhangs created when I-CreI cuts DNA have been shown to promote DNA repair through a mechanism called “homology directed repair,” or HDR. 3’ overhangs are stretches of unpaired nucleotides in the end of a DNA molecule. A genome editing technology that facilitates cellular repair through HDR enables applications that require a gene insertion or gene repair. Unlike other editing endonucleases, I-CreI creates four base 3’ overhangs when it cuts its DNA site, which increases the likelihood that the cell will repair the DNA cut through HDR. As such, the DNA cuts created by I-CreI can be exploited to efficiently insert or repair DNA, consistent with the natural role of I-CreI in catalyzing the targeted insertion of a gene in algae. |

|

|

• |

Programmability. I-CreI recognizes its DNA target site through a complex network of interactions that is challenging to re-program for new editing applications involving different DNA sequences. The challenges associated with re-programming I-CreI have, historically, hampered its adoption by the genome editing community in favor of more easily engineered endonucleases. This engineering challenge represents a high barrier to entry and has enabled us to secure a strong intellectual property position and control over what we believe to be a superior genome editing technology. |

Other than the key programming challenge, we believed that the differentiated properties of I-CreI cited above made it an ideal “scaffold” for the development of novel genome editing tools. Moreover, we believed those properties were differentiated enough from other editing technologies to merit substantial investment in overcoming the key challenge of programmability. To that end, we invested 15 years of research effort to develop a robust, proprietary protein engineering method that now enables us to consistently re-program I-CreI to direct it to targeted sites in a genome. We call our approach ARCUS.

Our ARCUS Genome Editing Platform

ARCUS is a collection of protein engineering methods that we developed specifically to re-program the DNA recognition properties of I-CreI. In nature, the I-CreI endonuclease recognizes and cuts a DNA sequence in the genome of algae. To apply I-CreI to genome editing in other cells or organisms, we must modify it to recognize and cut a different DNA sequence for each new application we pursue. Since the I-CreI endonuclease evolved to recognize its target sequence in the algae genome with a high degree of selectivity, as supported by scientific literature, it was necessary for us to develop sophisticated protein engineering methods to re-engineer I-CreI endonucleases to bind and cut a different DNA sequence. Using the ARCUS process, we create customized endonucleases for particular applications. We call these custom endonucleases “ARCUS nucleases.” Our process is proprietary and core components are claimed in an extensive international patent portfolio. Moreover, since the ARCUS process involves a sophisticated blend of protein engineering art and science, each ARCUS nuclease we create is novel and, we believe, patentable. As of December 31, 2020, we have

7

obtained U.S. patents with claims directed to six ARCUS nucleases as compositions of matter, and currently claim over 290 ARCUS nucleases as compositions of matter in pending U.S. and foreign patent applications.

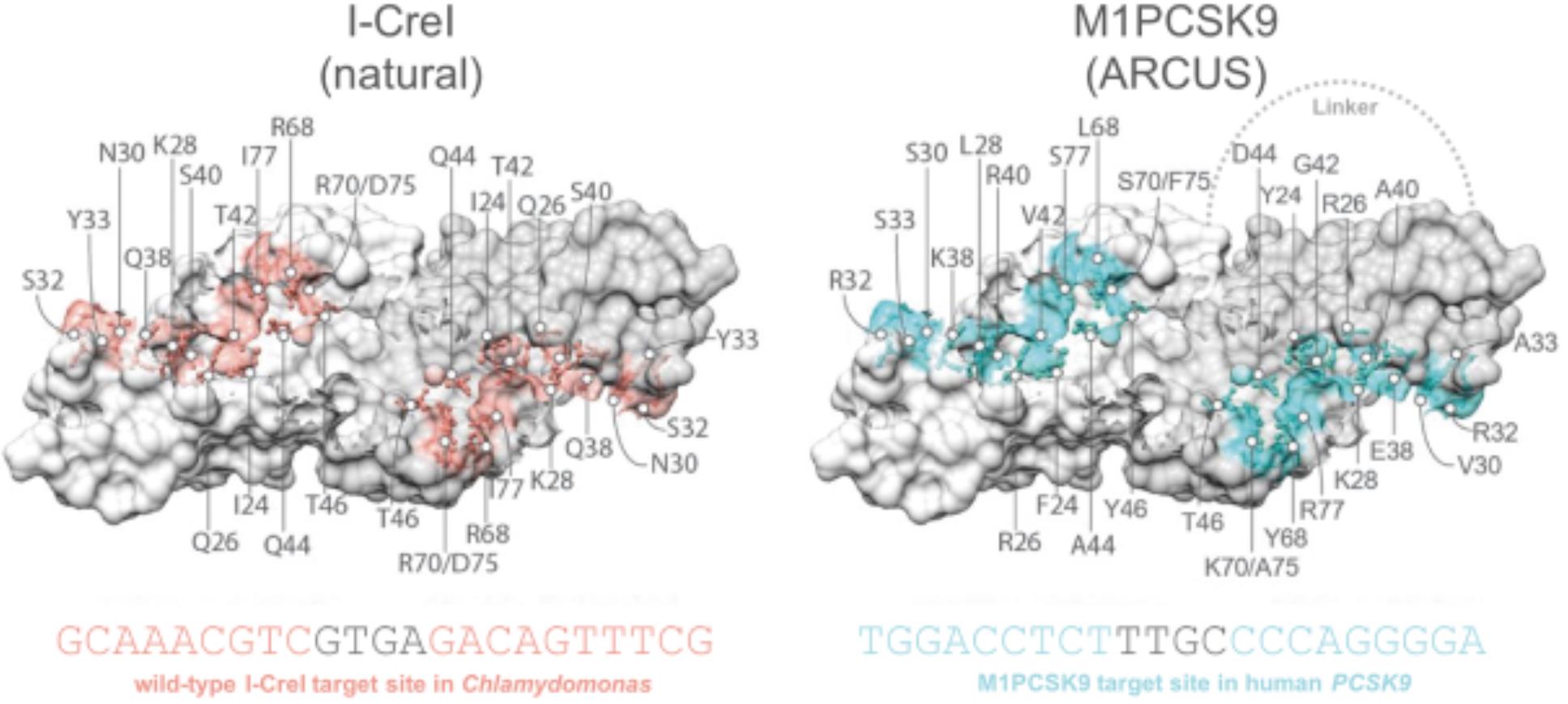

Our objective with ARCUS is to redirect I-CreI to a new location in a genome without compromising its editing abilities. To accomplish this, we modify the parts of the enzyme that, as reported by scientific literature, are involved in recognizing the specific DNA target site. These enzyme parts are also reported to comprise the I-CreI active site and to be involved in anchoring the enzyme to its DNA site in the algae genome. In our preclinical studies, we have observed that these modifications allowed us to control how tightly an engineered variant of I-CreI binds to its intended DNA site, as well as how quickly it cuts, in a plant or animal cell. By adjusting these two parameters, we observed that we can generally control the efficiency with which the engineered endonuclease cuts its intended target site or any potential off-target sites.

The natural I-CreI target site is pseudo-palindromic, meaning the first half of the sequence is approximately a mirror image of the second half of the sequence. Palindromic DNA sites are rare in most genomes so it was necessary for us to develop additional technology that would overcome this limitation on the diversity of DNA sites that we can target. To this end, the ARCUS process involves the production of two re-programmed I-CreI proteins for each target site. These two different proteins are then linked together into a single protein that can be expressed from a single gene. This approach, called a “single-chain endonuclease,” represents a major advancement in I-CreI engineering because it enables our ARCUS nucleases to recognize and cut non-palindromic target sites using an endonuclease that, like natural I-CreI, is very small and easy to deliver to cells.

The graphic below depicts the molecular structure of natural I-CreI in comparison to an engineered ARCUS nuclease called “M1PCSK9.” The regions of the structures colored in pink or cyan represent the amino acid building blocks that are responsible for contacting the DNA target site and determining the sequence of DNA bases that the endonuclease recognizes and cuts. The DNA target sites recognized by the two endonucleases are shown below the structures.

Since creating an ARCUS nuclease requires such extensive reengineering of I-CreI, it is, generally, an iterative process that involves multiple cycles of design and testing. We can typically produce a first-generation ARCUS nuclease in seven weeks. First-generation nucleases are suitable for research and development, proof-of-concept studies or other non-therapeutic applications. For therapeutic applications requiring the lowest possible off-targeting, however, we are rarely satisfied with generation one and each endonuclease undergoes extensive optimization. To this end, we thoroughly interrogate the nuclease with respect to its on-and off-target cutting properties using ultra-sensitive tests that we developed specifically for use with ARCUS. These results then inform our design of a second-generation nuclease with the goal of optimizing on-target efficiency while minimizing off-target cutting. Therapeutic ARCUS nucleases typically require two to four cycles of design and testing, often resulting in off-target cutting frequencies that are below the limit of detection with our most sensitive assays. This process can take six months or longer and has resulted in development of “therapeutic-grade” editing endonucleases.

The ARCUS process is robust and reproducible. It enables us to create engineered variants of the I-CreI endonuclease that recognize and cut DNA sites that bear little resemblance to I-CreI’s natural target site. Importantly, however, ARCUS retains the attributes of I-CreI that we believe make it highly suitable as a genome editing endonuclease for complex commercial applications. We expect ARCUS nucleases to be exquisitely specific as a result of the natural structure of I-CreI and the intricate design process we employ to create them. We believe ARCUS nucleases are the smallest and easiest to deliver genome editing endonucleases. Like I-CreI, in our preclinical studies, ARCUS nucleases have been observed to produce DNA cuts with 3’ overhangs that promote HDR, facilitating

8

gene insertions and gene repairs in addition to gene knockouts. We believe that these attributes will enable us to translate ARCUS into patient-based clinical trials and a wide array of product candidates that have the potential to address the limitations of other genome editing technologies and improve life.

We believe that ARCUS is a leading genome editing platform for therapeutic and food applications. Realizing the potential of ARCUS, however, requires supporting technologies and capabilities. To facilitate the potential commercial deployment of ARCUS in different fields, we surround it with ancillary technologies, domain expertise and infrastructure specific to that area of development. Our goal is to leverage ARCUS to build additional product-development platforms designed to rapidly generate new products in a given field.

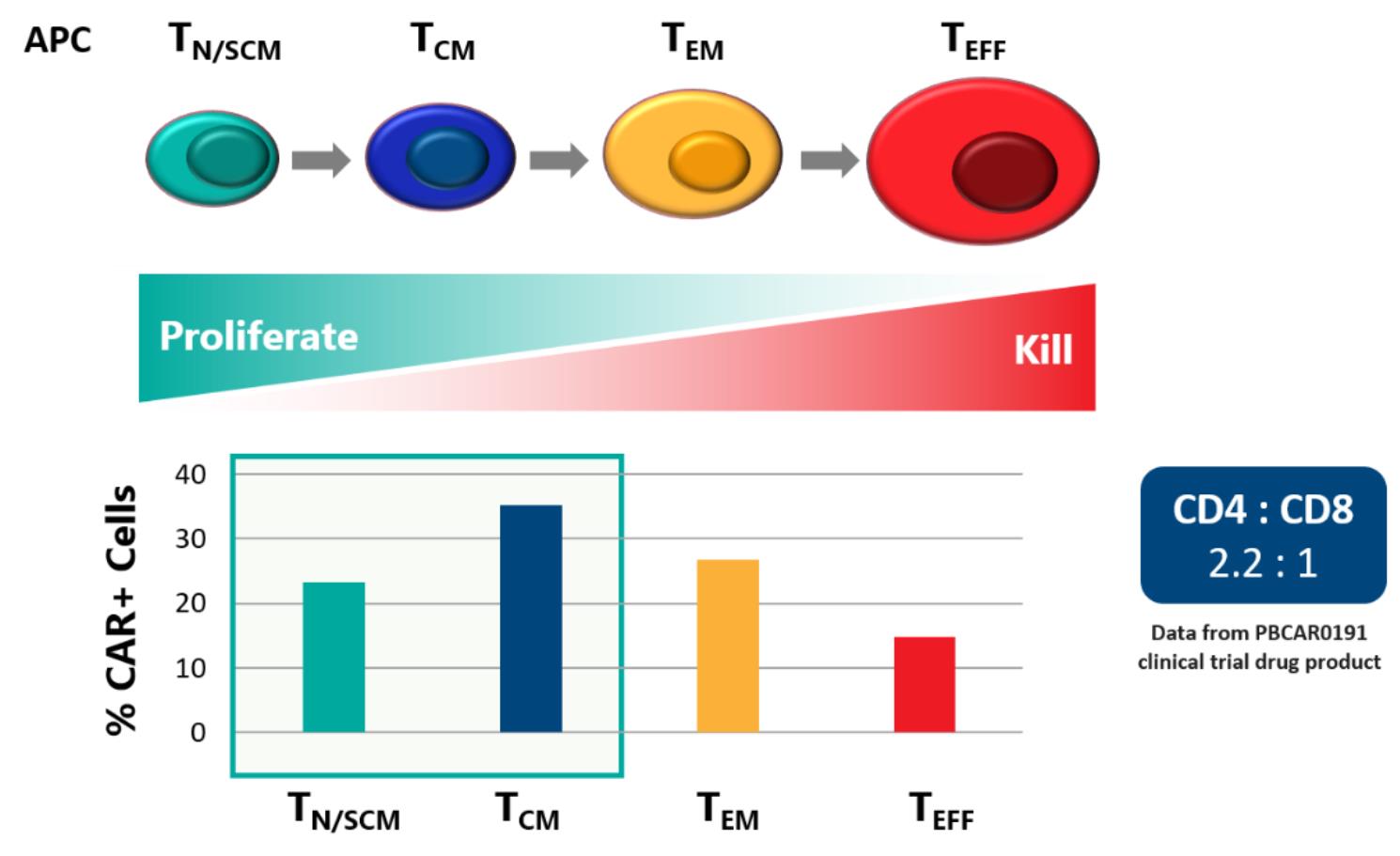

Our Allogeneic CAR T Immunotherapy Platform

We are leveraging the properties of ARCUS in an integrated platform for the development and large-scale production of off-the-shelf (allogeneic) CAR T cell immunotherapies. A key to the success of this platform is our proprietary, one-step method for modifying the genetics of T cells from a healthy donor to make them detect and kill cancer cells. This method allows us to produce allogeneic CAR T therapy candidates with a potentially optimal phenotype for clinical development and scaled manufacturing. We have demonstrated that our approach yields an allogeneic product with a high proportion of naïve and central memory CAR T cells, which are the T cell phenotypes that have previously correlated best with good clinical benefit and fewer adverse events compared with terminally differentiated effector T cells. Additionally, because these cells are derived from healthy donors and maintain the phenotypic characteristics described, it is our hypothesis that they will be more capable of controlled in vivo expansion and tumor killing without requiring harsh lymphodepletion regimens to be administered to the patient. As such, we believe that our allogeneic CAR T cell platform will greatly increase patient access to these cutting-edge treatments.

CAR T Cell Therapies

CAR T cell therapy is a form of cancer immunotherapy that uses a patient’s immune system to kill cancer cells. T cells are a component of the immune system that can distinguish pathogen-infected or tumor cells from healthy cells and kill them. Recognition of pathogen-infected cells or tumor cells occurs through a protein called a TCR, that is expressed on the surface of T cells. Tumor cells, however, have evolved numerous ways to evade TCR-mediated killing by T cells. In CAR T cell therapy, T cells are engineered ex vivo to express a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, that recognizes specific tumor cell surface targets and allows the T cells to function independently of the TCR, thus circumventing tumor cells’ evasion of the TCR. CAR T cell therapy has been shown in clinical trials to be an effective treatment for patients who have not responded to traditional cancer treatments, and there are now two FDA approved CAR T cell products available to treat certain types of leukemia and lymphoma.

The most common form of CAR T cell therapy, which includes the two approved therapies, is referred to as “autologous” CAR T cell therapy because the CAR T cells are generated using T cells taken directly from the cancer patient. T cells are harvested from the patient, genetically engineered ex vivo to express a CAR, and then injected back into the patient. While autologous CAR T cell therapy has been shown to be effective for treating certain tumor types, it has several significant drawbacks:

|

|

• |

Patient eligibility. Many patients may not be eligible for the treatment because their cancer has lowered their T cell numbers and T cell quality, or because the risk of undergoing the process to harvest T cells is too great. |

|

|

• |

Consistency. Since each autologous therapy is, by definition, unique, it is difficult to define standards of safety and efficacy or to thoroughly assess the quality of the product prior to infusion into the patient. |

|

|

• |

Delay in treatment. Because the process to make autologous CAR T cells can take several weeks, there is a significant delay in treating what can often be very aggressive tumors. Patients’ disease often progresses before they can receive the CAR T therapy, or if manufacturing complications such as contamination, mislabeling or low yield are encountered, the patient may not survive long enough to attempt manufacturing a second time. |

|

|

• |

Cost. The autologous CAR T cell manufacturing process is complex and expensive and must be performed, in its entirety, for each patient. As such, scaling of the manufacturing process is exceedingly difficult, and the cost of product manufacturing has resulted in high treatment costs per patient. This high cost of treatment, along with the practical complexities described above, limits the availability of autologous CAR T cell therapies to patients. |

9

Our Approach to Allogeneic CAR T Cells

We believe that the use of allogeneic, or donor-derived, CAR T cells will address many of the challenges associated with autologous CAR T cell therapy. An allogeneic approach allows selection of donors using specific criteria to define “healthy” T cells possessing specific phenotypes, which we believe are important to clinical efficacy and which may lessen the product-to-product variability seen in autologous therapies. Donor-derived cells could be used in any patient, eliminating the “one patient: one product” burden of autologous CAR T cell therapies. Because healthy donors would provide the starting material, patients that were too sick or otherwise unqualified for an autologous approach may benefit from an allogeneic CAR T cell therapy. Additionally, patients receiving an off-the-shelf allogeneic treatment would not have to wait for the manufacture of a personalized autologous treatment, which could be further delayed by manufacturing difficulties. By scaling the manufacturing of CAR T cells and optimizing the manufacturing process for a specific pool of donors, we believe that allogeneic CAR T cells can be manufactured at costs that are significantly lower than autologous CAR T cells and that will, over time, approach the manufacturing costs for conventional biologic drugs. These potential advantages of an allogeneic approach should allow for a safer, more predictable product with defined quality standards and significantly increase patient access.

We have used the unique qualities of ARCUS to create a one-step cell engineering process for allogeneic CAR T cells that we believe yields a well-defined cell product and is designed to maintain naïve and central memory T cell phenotypes throughout the CAR T manufacturing process; we believe this is of paramount importance for an optimized CAR T therapy. To produce an allogeneic CAR T cell, it is necessary to make two changes to the DNA of T cells from a healthy donor. First, it is necessary to knock out the gene that encodes the TCR to prevent the donor-derived T cells from eliciting GvHD in the patient. The TCR is actually a complex of several different components encoded by different genes, and knocking out any one of them is generally sufficient to prevent the TCR from functioning. Second, it is necessary to add, or knock in, a gene that encodes the CAR to give the T cells the ability to recognize and kill cancer cells. We developed a proprietary, one-step method for achieving both genetic changes simultaneously. This method, aspects of which are protected by nine issued U.S. patents, involves the use of ARCUS to target the insertion of a CAR gene directly into the gene that encodes the alpha subunit of the TCR. This approach adds the DNA encoding the CAR while simultaneously disrupting the DNA encoding the TCR, essentially replacing one gene with the other.

One-step engineered allogeneic CAR T cells

10

We believe that our one-step engineering approach, and the differentiated attributes of the ARCUS nuclease used to implement it, will overcome many of the critical challenges associated with allogeneic CAR T cell production as follows:

|

|

• |

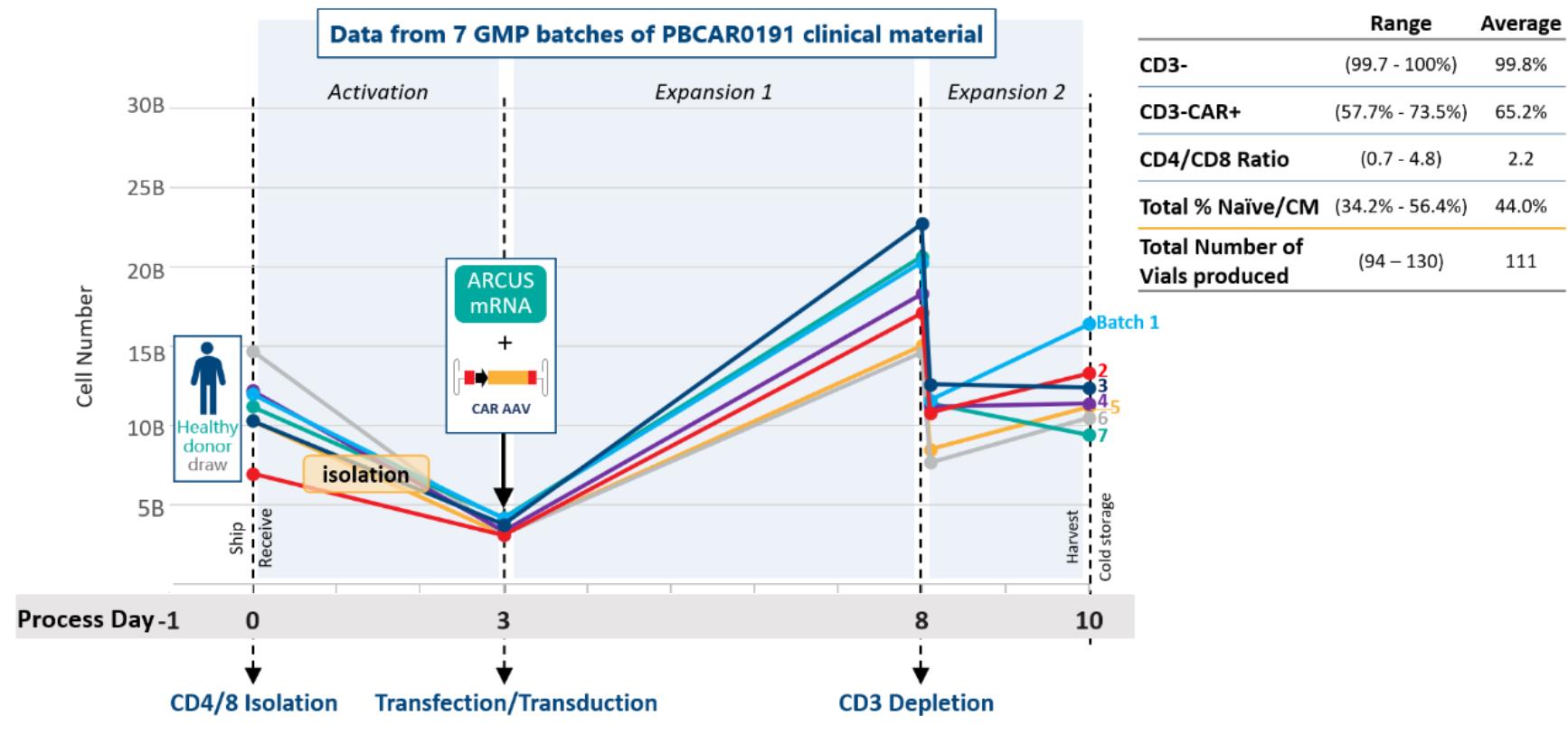

T cell phenotype. According to scientific literature, T cell phenotype has a profound impact on the efficacy of CAR T cell therapy. Specifically, “young” CAR T cells with naïve and central memory phenotypes have been observed to undergo the most robust expansion following administration, which leads to a therapeutic effect. Therefore, we have established a T cell platform that is designed to maximize the percentage of cells with these ideal phenotypes. Our process starts with carefully screening donors to identify individuals with high percentages of naïve or central memory T cells and a ratio of CD4:CD8 T cells that we believe should yield the most potent cell product. To this end, we have developed our own set of analytics for screening candidate donors and have put significant effort into identifying individuals with the desired T cell profiles. We then use proprietary growth strategies and media to maintain naïve and central memory T cell phenotypes throughout the CAR T manufacturing process. We believe this is of paramount importance for an optimized CAR T therapy. Importantly, our one-step genome editing approach avoids making multiple breaks to the T cell’s DNA and also contributes to minimizing cell processing time, which helps prevent the CAR T cells from differentiating during the process. We believe our 10-day allogeneic manufacturing process is the shortest established process in the industry. The figure below shows results from seven full-scale manufacturing campaigns, each of which produced a cGMP batch of PBCAR0191 with desired product specifications. |

The figure below shows phenotype data from PBCAR0191 CAR T cells that were produced as drug product for our ongoing Phase 1/2a clinical trial in adult patients with R/R NHL and R/R B-ALL. The drug product comprises naïve (TN/SCM) and central memory (TCM) T cells.

11

|

|

• |

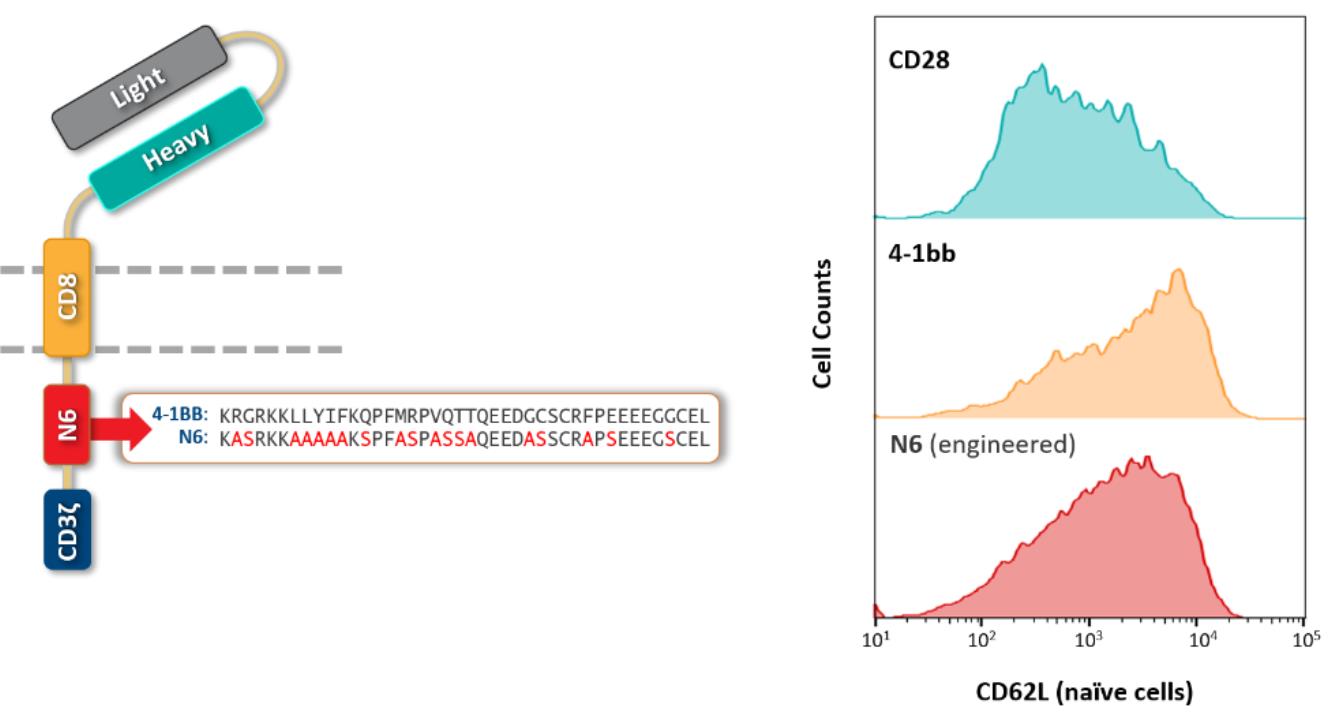

Novel co-stimulatory domain. Our genetically engineered CAR T cells incorporate a novel, proprietary, costimulatory domain called N6, which enables us to enhance cell proliferation and effector function while preserving cell phenotype. We engineered N6 to improve on the function of the 4-1bb costimulatory domain commonly used in autologous CAR T products. Our preclinical data suggests that, compared to 4-1bb, N6 provides an activation signal to the CAR T cells that better preserves cell expansion potential while maintaining naïve cell phenotype following exposure to cancer cells. We also believe N6 can help avoid CAR T cell hyperstimulation, which can contribute to adverse events seen with autologous products. |

|

|

• |

Consistency. By consistently targeting the same insertion of the CAR gene to a defined location in the DNA of the cell, we are able to produce populations of T cells that are identical at the DNA level. This makes the cells in our CAR T cell drug formulation less heterogeneous as compared to manufacturing processes that use lentiviral vectors. Importantly, our genome editing process gives us greater control over the amount of CAR that is expressed on the surface of each CAR T cell, which determines how easily the CAR T cell is activated once it encounters a cancer cell. This allows us to “fine-tune” the CAR T cells to ensure that they respond appropriately to the cancer but do not become hyper‑activated or exhausted. The below comparison demonstrates the difference in consistency achieved by using lentivirus delivery compared with targeted delivery through an ARCUS nuclease. CAR T cells produced using ARCUS exhibit reduced cell-to-cell variability as well as more controlled levels of CAR gene expression depending on whether the cells are tuned for high expression or low expression. |

|

|

• |

Scalability. To realize the potential benefits of allogeneic CAR T cell therapy, it will be important to manufacture as many cells as possible in each batch in accordance with cGMP. Scaling efficiently requires scale-up at every step in the process and, as with all drug manufacturing, process development takes significant time and capital. In July 2019, we opened our |

12

|

|

Manufacturing Center for Advanced Therapeutics (“MCAT”) facility, which we believe is the first in-house cGMP compliant manufacturing facility dedicated to genome-edited, off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy product candidates in the United States. We made the decision early in the development of our CAR T cell platform to invest in process development and manufacturing rather than initiating clinical trials with a process that would not fully support development and commercialization. We did this, in part, because we believed that several attributes of ARCUS, such as high specificity and high knock-in efficiency, would allow us to scale manufacturing more effectively than our competitors. As a consequence of our early investment and the one-step editing method enabled by ARCUS, we have scaled our manufacturing process today, adding in-house capabilities through the opening of our MCAT facility. During 2020, we completed technology transfer of PBCAR0191 and PBCAR20A to MCAT, as well as manufactured the first batch and clinical trial material for PBCAR269A and produced clinical trial material for PBCAR19B stealth cell. |

Key features of Precision’s allogeneic CAR T platform

Preventing CAR T Cell Rejection

A patient’s immune system is expected to recognize allogeneic CAR T cells as foreign and destroy or reject the cells. This rejection could limit the efficacy of the CAR T therapy if the cells do not persist long enough in the patient to eradicate the tumor. Patients who receive CAR T therapy are typically preconditioned prior to being given the cell therapy using lymphodepleting drugs such as cyclophosphamide or fludarabine, which suppress the immune system of the patient. We believe that the degree of preconditioning can be modified by adjusting the doses of the cyclophosphamide or fludarabine to prevent CAR T cell rejection by patients who receive our treatments due to our unique approach to producing CAR T cells. Our CAR T production process preserves T cell phenotypes that we believe are highly expansile in vivo and therefore do not require an aggressive lymphodepletion regime to survive and proliferate in the body.

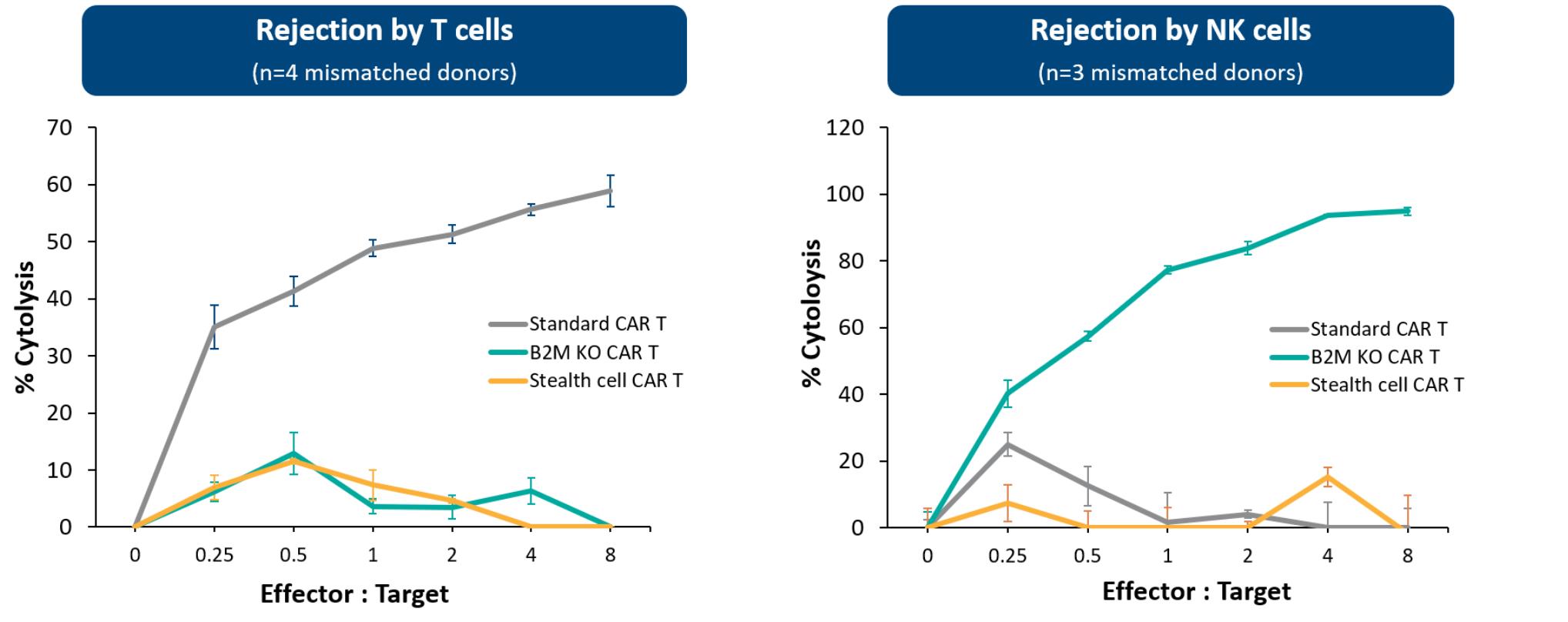

13

We expect to begin the Phase 1 study of PBCAR19B, our next-generation, stealth cell, CD19 allogenic CAR T candidate for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma by mid-2021. The stealth cell technology is a modified CAR T vector that is designed to suppress expression of a gene called beta-2-microglobulin, or B2M, in CAR T cells using a short-hairpin RNA, or shRNA, and enable expression of a transgenic HLA-E molecule on the cell surface. B2M is a component of the major histocompatibility complex type 1 (“MHC-I”), a cell surface receptor which enables alloreactive T cell recognition and activation. Suppression of B2M expression leads to reduced cell-surface expression of major histocompatibility complex components HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C. In preclinical studies, we and others have observed that suppression or elimination of B2M reduces the rejection of CAR T cells by alloreactive T cells from an unrelated individual. However, we have found that reduction of cell-surface HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C expression provokes rejection of the CAR T cells by an alternative immune cell called natural killer, or NK cells. Decreased expression of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C therefore necessitates an additional modification to enable overexpression of HLA-E, a non-classical MHC -I that inhibits cytotoxic killing by NK cells by interacting with inhibitory receptors on the NK cell surface (Gornalusse et al, 2017; Lanza et al, 2019). Thus, the “stealth cell” is designed to avoid rejection by both alloreactive cytotoxic T cells and NK cells, which we believe has the potential to increase the ability of these cells to expand, persist, and mediate anti-tumor activity in unrelated recipients as summarized in the figure below.

Pre-clinical studies showed anti-CD19 stealth CAR T cells resisted rejection by allo-reactive

T cells and NKs in mixed-lymphocyte reactions

14

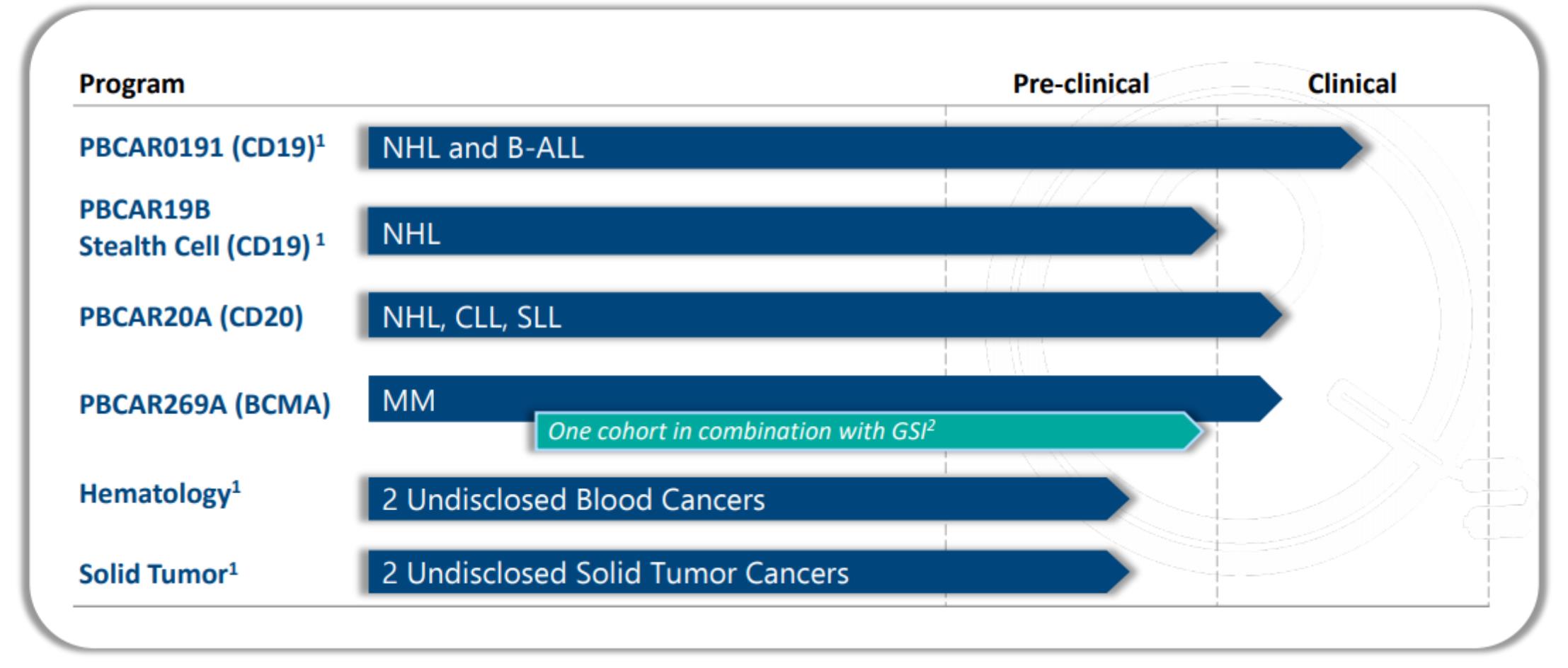

Our Allogeneic CAR T Immunotherapy Pipeline

1 In partnership with Servier.

2 In combination with gamma secretase inhibitor from SpringWorks Therapeutics.

We are leveraging our CAR T cell platform to develop product candidates against validated CAR T cell targets. By focusing on validated targets, we seek to avoid many technical hurdles associated with early clinical development and can validate our allogeneic platform in patients with fewer variables. This approach also allows us to leverage the abundance of available public resources for these targets, including CARs, cell and animal models, and clinical protocols. We believe that our modular CAR T platform will allow us to leverage proof-of-concept from our ongoing and planned initial human trials for multiple other CAR T programs. We believe that we have developed the first allogeneic CAR T cell platform capable of producing drug product at scale, with a potentially optimal cell profile for therapeutic efficacy and true off-the-shelf delivery without the need for harsh and potentially toxic lymphodepletion. We believe that the combination of these factors, along with our next generation ARCUS technology, puts us in a differentiated position to become the leader in the development of allogeneic CAR T therapies.

The first four product candidates in our allogeneic CAR T cell development pipeline are:

|

|

• |

PBCAR0191. We are developing PBCAR0191, an allogeneic anti-CD19 CAR T cell product candidate for the treatment of adult R/R NHL and adult R/R B-cell precursor ALL. CD19 is a protein that is expressed on the surface of B cells and is a well-validated target for CAR T cell therapy. The three currently marketed autologous CAR T cell therapy products also target CD19. In February 2016, we entered into the Servier Agreement, pursuant to which we have agreed to develop allogeneic CAR T cell therapies for CD19. |

15