Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EX-32.2 - EXHIBIT 32.2 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex322.htm |

| EX-32.1 - EXHIBIT 32.1 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex321.htm |

| EX-31.2 - EXHIBIT 31.2 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex312.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EXHIBIT 31.1 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex311.htm |

| EX-23.1 - EXHIBIT 23.1 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex231.htm |

| EX-21.1 - EXHIBIT 21.1 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex211.htm |

| EX-12.1 - EXHIBIT 12.1 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex121.htm |

| EX-10.27 - EXHIBIT 10.27 - DAVITA INC. | dva-123117xex1027.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2017

Commission File Number: 1-14106

DAVITA INC.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in charter)

Delaware | 51-0354549 | |

(State of incorporation) | (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) | |

2000 16th Street

Denver, CO 80202

Telephone number (303) 405-2100

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

Title of each class: | Name of each exchange on which registered: | |

Common Stock, $0.001 par value | New York Stock Exchange | |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act:

None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports) and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K (§229.405 of this chapter) is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. (Check one):

Large accelerated filer | ☒ | Accelerated filer | ☐ | ||

Non-accelerated filer | ☐ | (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) | Smaller reporting company | ☐ | |

Emerging growth company | ☐ | ||||

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

As of June 30, 2017, the aggregate market value of the Registrant's common stock outstanding held by non-affiliates based upon the closing price on the New York Stock Exchange was approximately $12.4 billion.

As of January 31, 2018, the number of shares of the Registrant’s common stock outstanding was approximately 182.0 million shares.

Documents incorporated by reference

Portions of the Registrant’s proxy statement for its 2018 annual meeting of stockholders are incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K.

PART I

Item 1. Business

We were incorporated as a Delaware corporation in 1994. Our annual report on Form 10-K, quarterly reports on Form 10-Q, current reports on Form 8-K and amendments to those reports filed or furnished pursuant to section 13(a) or 15(d) of the Exchange Act are made available free of charge through our website, located at http://www.davita.com, as soon as reasonably practicable after the reports are filed with or furnished to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC also maintains a website at http://www.sec.gov where these reports and other information about us can be obtained. The contents of our website are not incorporated by reference into this report.

Overview of DaVita Inc.

The Company has consisted of two major divisions, DaVita Kidney Care (Kidney Care) and DaVita Medical Group (DMG). Kidney Care is comprised of our U.S. dialysis and related lab services, our ancillary services and strategic initiatives, including our international operations, and our corporate administrative support. Our U.S. dialysis and related lab services business is our largest line of business and is a leading provider of kidney dialysis services in the U.S. for patients suffering from chronic kidney failure, also known as end stage renal disease (ESRD). DMG is a patient- and physician-focused integrated healthcare delivery and management company with over two decades of providing coordinated, outcomes-based medical care in a cost-effective manner.

On December 5, 2017, we entered into an equity purchase agreement to sell our DMG division to Collaborative Care Holdings, LLC (Optum), a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group Inc. The transaction is expected to close in 2018 and is subject to regulatory approval and other customary closing conditions. As a result of this pending transaction, the DMG business has been reclassified as held for sale and its results of operations are reported as discontinued operations for all periods presented in our consolidated financial statements included in this report.

For financial information about our DMG business see Note 21 to the consolidated financial statements included in this report.

Kidney Care Division

U.S. dialysis and related lab services business overview

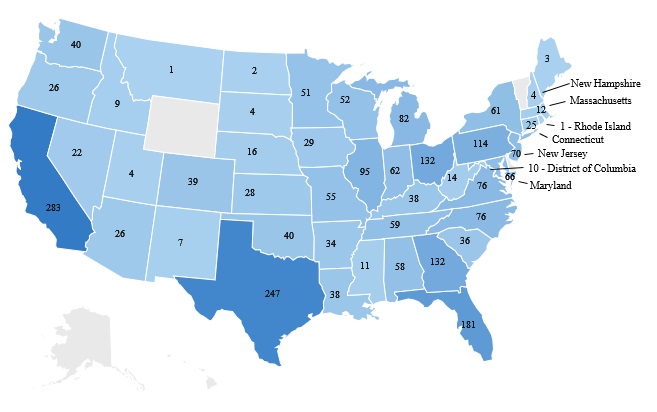

Our U.S. dialysis and related lab services business is a leading provider of kidney dialysis services for patients suffering from ESRD. As of December 31, 2017, we provided dialysis and administrative services in the U.S. through a network of 2,510 outpatient dialysis centers in 46 states and the District of Columbia, serving a total of approximately 197,800 patients. We also provide acute inpatient dialysis services in approximately 900 hospitals and related laboratory services throughout the U.S.

The loss of kidney function is normally irreversible. Kidney failure is typically caused by Type I and Type II diabetes, high blood pressure, polycystic kidney disease, long-term autoimmune attack on the kidney and prolonged urinary tract obstruction. ESRD is the stage of advanced kidney impairment that requires continued dialysis treatments or a kidney transplant to sustain life. Dialysis is the removal of toxins, fluids and salt from the blood of patients by artificial means. Patients suffering from ESRD generally require dialysis at least three times a week for the rest of their lives.

According to the United States Renal Data System, there were over 495,000 ESRD dialysis patients in the U.S. in 2015. The underlying ESRD dialysis patient population has grown at an approximate compound rate of 3.8% from 2000 to 2015, the latest period for which such data is available. The growth rate is attributable to the aging of the U.S. population, increased incidence rates for diseases that cause kidney failure such as diabetes and hypertension, lower mortality rates for dialysis patients and growth rates of minority populations with higher than average incidence rates of ESRD.

Since 1972, the federal government has provided healthcare coverage for ESRD patients under the Medicare ESRD program regardless of age or financial circumstances. ESRD is the first and only disease state eligible for Medicare coverage both for dialysis and dialysis-related services and for all benefits available under the Medicare program. For patients with Medicare coverage, all ESRD payments for dialysis treatments are made under a single bundled payment rate. See page 6 for further details.

Although Medicare reimbursement limits the allowable charge per treatment, it provides industry participants with a relatively predictable and recurring revenue stream for dialysis services provided to patients without commercial insurance. For the year ended December 31, 2017, approximately 89.5% of our total dialysis patients were covered under some form of

2

government-based programs, with approximately 74.9% of our dialysis patients covered under Medicare and Medicare-assigned plans.

Treatment options for ESRD

Treatment options for ESRD are dialysis and kidney transplantation.

Dialysis options

• | Hemodialysis |

Hemodialysis, the most common form of ESRD treatment, is usually performed at a freestanding outpatient dialysis center, at a hospital-based outpatient center, or at the patient’s home. The hemodialysis machine uses an artificial kidney, called a dialyzer, to remove toxins, fluids and salt from the patient’s blood. The dialysis process occurs across a semi-permeable membrane that divides the dialyzer into two distinct chambers. While blood is circulated through one chamber, a pre-mixed fluid is circulated through the other chamber. The toxins, salt and excess fluids from the blood cross the membrane into the fluid, allowing cleansed blood to return back into the patient’s body. Each hemodialysis treatment that occurs in the outpatient dialysis centers typically lasts approximately three and one-half hours and is usually performed three times per week.

Hospital inpatient hemodialysis services are required for patients with acute kidney failure primarily resulting from trauma, patients in early stages of ESRD and ESRD patients who require hospitalization for other reasons. Hospital inpatient hemodialysis is generally performed at the patient’s bedside or in a dedicated treatment room in the hospital, as needed.

Some ESRD patients who are healthier and more independent may perform home-based hemodialysis in their home or residence through the use of a hemodialysis machine designed specifically for home therapy that is portable, smaller and easier to use. Patients receive training, support and monitoring from registered nurses, usually in our outpatient dialysis centers, in connection with their dialysis treatment. Home-based hemodialysis is typically performed with greater frequency than dialysis treatments performed in outpatient dialysis centers and on varying schedules.

• | Peritoneal dialysis |

Peritoneal dialysis uses the patient’s peritoneal or abdominal cavity to eliminate fluid and toxins and is typically performed at home. The most common methods of peritoneal dialysis are continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), and continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis (CCPD). Because it does not involve going to an outpatient dialysis center three times a week for treatment, peritoneal dialysis is an alternative to hemodialysis for patients who are healthier, more independent and desire more flexibility in their lifestyle.

CAPD introduces dialysis solution into the patient’s peritoneal cavity through a surgically placed catheter. Toxins in the blood continuously cross the peritoneal membrane into the dialysis solution. After several hours, the patient drains the used dialysis solution and replaces it with fresh solution. This procedure is usually repeated four times per day.

CCPD is performed in a manner similar to CAPD, but uses a mechanical device to cycle dialysis solution through the patient’s peritoneal cavity while the patient is sleeping or at rest.

Kidney transplantation

Although kidney transplantation, when successful, is generally the most desirable form of therapeutic intervention, the shortage of suitable donors, side effects of immunosuppressive pharmaceuticals given to transplant recipients and dangers associated with transplant surgery for some patient populations limit the use of this treatment option.

U.S. Dialysis and related lab services we provide

Outpatient hemodialysis services

As of December 31, 2017, we operated or provided administrative services through a network of 2,510 outpatient dialysis centers in the U.S. that are designed specifically for outpatient hemodialysis. In 2017, our overall network of U.S. outpatient dialysis centers increased by 160 primarily as a result of the opening of new dialysis centers, net of center closures, divestitures, and acquisitions, representing a total increase of approximately 6.8% from 2016.

As a condition of our enrollment in Medicare for the provision of dialysis services, we contract with a nephrologist or a group of associated nephrologists to provide medical director services at each of our dialysis centers. In addition, other

3

nephrologists may apply for practice privileges to treat their patients at our centers. Each center has an administrator, typically a registered nurse, who supervises the day-to-day operations of the center and its staff. The staff of each center typically consists of registered nurses, licensed practical or vocational nurses, patient care technicians, a social worker, a registered dietician, biomedical technician support and other administrative and support personnel.

Under Medicare regulations, we cannot promote, develop or maintain any kind of contractual relationship with our patients that would directly or indirectly obligate a patient to use or continue to use our dialysis services, or that would give us any preferential rights other than those related to collecting payments for our dialysis services. Our total patient turnover, which is based upon all causes, averaged approximately 26% in 2017 and 25% in 2016. However, in 2017, the overall number of patients to whom we provided services in the U.S. increased by approximately 5.4% from 2016, primarily from the opening of new dialysis centers and acquisitions, and continued growth within the industry.

Hospital inpatient hemodialysis services

As of December 31, 2017, we provided hospital inpatient hemodialysis services, excluding physician services, to patients in approximately 900 hospitals throughout the U.S. We render these services based on a contracted per-treatment fee that is individually negotiated with each hospital. When a hospital requests our services, we typically administer the dialysis treatment at the patient’s bedside or in a dedicated treatment room in the hospital, as needed. In 2017, hospital inpatient hemodialysis services accounted for approximately 5.0% of our U.S. dialysis revenues and 4.0% of our total U.S. dialysis treatments.

Home-based hemodialysis services

Many of our outpatient dialysis centers offer certain support services for dialysis patients who prefer and are able to perform either home-based hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis in their homes. Home-based hemodialysis support services consist of providing equipment and supplies, training, patient monitoring, on-call support services and follow-up assistance. Registered nurses train patients and their families or other caregivers to perform either home-based hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

ESRD laboratory services

We own two separately incorporated, licensed, clinical laboratories which specialize in ESRD patient testing. These specialized laboratories provide routine laboratory tests for dialysis and other physician-prescribed laboratory tests for ESRD patients and are an integral component of overall dialysis services that we provide. Our laboratories provide these tests predominantly for our network of ESRD patients throughout the U.S. These tests are performed to monitor a patient’s ESRD condition, including the adequacy of dialysis, as well as other medical conditions of the patient. Our laboratories utilize information systems which provide information to certain members of the dialysis centers’ staff and medical directors regarding critical outcome indicators.

Management services

We currently operate or provide management and administrative services pursuant to management and administrative services agreements to 39 outpatient dialysis centers located in the U.S. in which we either own a noncontrolling interest or are wholly-owned by third parties. Management fees are established by contract and are recognized as earned typically based on a percentage of revenues or cash collections generated by the outpatient dialysis centers.

Quality care

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) promotes high quality services in outpatient dialysis facilities treating patients with ESRD through its Quality Incentive Program (QIP). QIP associates a portion of payment directly with a facility’s performance on quality of care measures. Payment reductions result when a facility’s overall score on applicable measures does not meet established standards. For the fifth year in a row, we are an industry leader in QIP standards. We are industry leaders for catheter rates and also lead the industry for the total number of patients in our peritoneal dialysis program.

In addition, CMS' Five-Star Quality Rating system, is a rating system that assigns one to five stars to rate the quality of outcomes for dialysis facilities. The rating system provides patients reported information about any given dialysis facility and identifies differences in quality between facilities so that patients can make more informed decisions about where to receive treatment. For the last three years in which data is available, we have been a leader in the industry under the CMS Five-Star Quality Rating system.

4

Our facilities employ registered nurses, licensed practical or vocational nurses, patient care technicians, social workers, registered dieticians, biomedical technicians and other administrative and support teammates who aim to achieve superior clinical outcomes at our centers.

Our physician leadership in the Office of the Chief Medical Officer (OCMO) for our U.S. dialysis and related lab services business includes 16 senior nephrologists, led by our Chief Medical Officer, with a variety of academic, clinical practice, and clinical research backgrounds. Our Physician Council is an advisory body to senior management composed of eight physicians with extensive experience in clinical practice. In addition, we currently have nine Group Medical Directors.

Sources of revenue—concentrations and risks

Our U.S. dialysis and related lab services business net revenues represent approximately 86% of our consolidated net revenues for the year ended December 31, 2017. Our U.S. dialysis and related lab services revenues are derived primarily from our core business of providing dialysis services and related laboratory services and, to a lesser extent, the administration of pharmaceuticals and management fees generated from providing management and administrative services to certain outpatient dialysis centers, as discussed above.

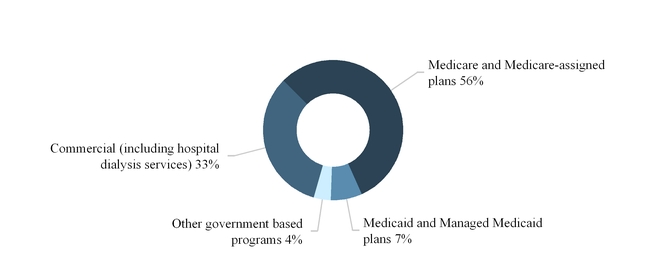

The sources of our U.S. dialysis and related lab services revenues are principally from government-based programs, including Medicare and Medicare-assigned plans, Medicaid and Managed Medicaid plans and commercial insurance plans.

The following graph summarizes our U.S. dialysis services revenues by source for the year ended December 31, 2017:

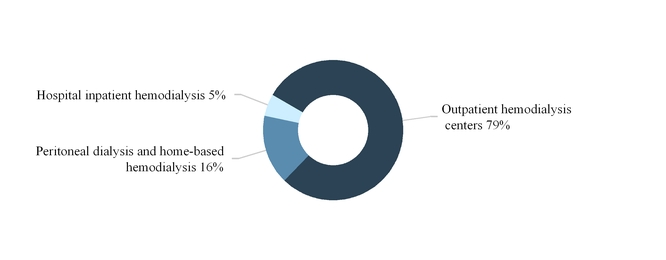

The following graph summarizes our U.S. dialysis services revenues by modality for the year ended December 31, 2017:

5

Medicare revenue

Government dialysis related payment rates in the U.S. are principally determined by federal Medicare and state Medicaid policy. For patients with Medicare coverage, all ESRD payments for dialysis treatments are made under a single bundled payment rate which provides a fixed payment rate to encompass all goods and services provided during the dialysis treatment, including certain pharmaceuticals, such as Epogen® (EPO), vitamin D analogs and iron supplements, irrespective of the level of pharmaceuticals administered to the patient or additional services performed. Most lab services are also included in the bundled payment. Under the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS), the bundled payments to a dialysis facility may be reduced by as much as 2% based on the facility’s performance in specified quality measures set annually by CMS through QIP, which was established by the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008. The bundled payment rate is also adjusted for certain patient characteristics, a geographic usage index and certain other factors.

Uncertainty about future payment rates remains a material risk to our business, as well as the potential implementation of or changes in coverage determinations or other rules or regulations by CMS or Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) that may impact reimbursement. An important provision in the law is an annual adjustment, or market basket update, to the ESRD PPS base rate. Absent action by Congress, the ESRD PPS base rate is automatically updated annually by a formulaic inflation adjustment.

In December 2013, CMS issued the 2014 final rule for the ESRD PPS, which phases in the payment reductions mandated by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA), as modified by the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014, which reduced our market basket inflation adjustment by 1.25% in both 2016 and 2017, and by 1% in 2018. In November 2017, CMS published the 2018 final rule for the ESRD PPS, which increased dialysis facilities’ bundled payment rate for 2018 relative to prior years. In particular, CMS projects that the 2018 final rule for the ESRD PPS will (i) increase the total payments to all ESRD facilities by 0.5% in 2018 compared to 2017; (ii) increase total payments to hospital-based ESRD facilities by 0.7% in 2018 compared to 2017; and (iii) increase total payments for freestanding facilities by 0.5% in 2018 compared to 2017. The 2018 final rule for the ESRD PPS also implements changes to the ESRD PPS outlier policy, broadening the pricing methodologies used to determine the cost of certain service drugs and biologicals in computing outlier payments when average sales price data is not available.

As a result of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) and subsequent activity in Congress, a $1.2 trillion sequester (across-the-board spending cuts) in discretionary programs took effect in 2013 reducing Medicare payments by 2%, which was subsequently extended through fiscal year 2027. These across-the-board spending cuts have affected and will continue to adversely affect our business, results of operations and financial condition. Although the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2018 passed in February 2018 enacts a two-year federal spending agreement and raises the federal spending cap on non-defense spending for fiscal years 2018 and 2019, the Medicare program is frequently mentioned as a target for spending cuts.

The CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center (Innovation Center) is working with various healthcare providers to develop, refine and implement Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and other innovative models of care for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. We are uncertain of the extent to which the long-term operation and evolution of these models of care, including ACOs, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative, Comprehensive ESRD Care (CEC) Model (which includes the development of ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs)), the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, the Duals Demonstration, or other models, will impact the healthcare market over time. Our U.S. dialysis business may choose to participate in one or several of these models either as a partner with other providers or independently. We currently participate in the CEC Model with the Innovation Center, including the ESCO organizations in the Arizona, Florida, and adjacent New Jersey and Pennsylvania markets. In areas where our U.S. dialysis business is not directly participating in this or other Innovation Center models, some of our patients may be assigned to an ACO, another ESRD Care Model, or another program, in which case the quality and cost of care that we furnish will be included in an ACO’s, another ESRD Care Model’s or other program’s calculations.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has also pledged to tie 50% of Medicare payments to quality or alternate payment models by the end of 2018. As new models of care emerge and evolve, we may be at risk for losing our Medicare patient base, which would have a materially adverse effect on our revenues, earnings and cash flows. Other initiatives in the government or private sector may also arise, including the development of models similar to ACOs, independent practice associations (IPAs) and integrated delivery systems or evolutions of those concepts which could adversely impact our business.

We anticipate that we will continue to experience increases in our operating costs in 2018 that will outpace any net Medicare rate increases that we may receive, which could significantly impact our operating results. In addition, we expect to continue experiencing increases in operating costs that are subject to inflation, such as labor and supply costs, including increases in maintenance costs and capital expenditures to improve, renovate and maintain our facilities, equipment and

6

information technology to meet changing regulatory requirements, regardless of whether there is a compensating inflation-based increase in Medicare payment rates or in payments under the bundled payment rate system.

ESRD patients receiving dialysis services become eligible for primary Medicare coverage at various times, depending on their age or disability status, as well as whether they are covered by a commercial insurance plan. Generally, for a patient not covered by a commercial insurance plan, Medicare becomes the primary payor for ESRD patients receiving dialysis services either immediately or after a three-month waiting period. For a patient covered by a commercial insurance plan, Medicare generally becomes the primary payor after 33 months, which includes the three-month waiting period, or earlier if the patient’s commercial insurance plan coverage terminates. When Medicare becomes the primary payor, the payment rates we receive for that patient shift from the commercial insurance plan rates to Medicare payment rates, which are on average significantly lower than commercial insurance rates.

Medicare pays 80% of the amount set by the Medicare system for each covered dialysis treatment. The patient is responsible for the remaining 20%. In most cases, a secondary payor, such as Medicare supplemental insurance, a state Medicaid program or a commercial health plan, covers all or part of these balances. Some patients who do not qualify for Medicaid, but otherwise cannot afford secondary insurance in the form of a Medicare Supplement Plan, can apply for premium payment assistance from charitable organizations to obtain secondary coverage. If a patient does not have secondary insurance coverage, we are generally unsuccessful in our efforts to collect from the patient the remaining 20% portion of the ESRD composite rate that Medicare does not pay. However, we are able to recover some portion of this unpaid patient balance from Medicare through an established cost reporting process by identifying these Medicare bad debts on each center’s Medicare cost report.

The 21st Century Cures Act, enacted in December 2016, included a provision that will allow Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD to choose a Medicare Advantage plan. Until the effective date of this law, this choice is available only to Medicare beneficiaries without ESRD. The ESRD related provisions of the 21st Century Cures Act are scheduled to take effect in 2021.

Medicaid revenue

Medicaid programs are state-administered programs partially funded by the federal government. These programs are intended to provide health coverage for patients whose income and assets fall below state-defined levels and who are otherwise uninsured. These programs also serve as supplemental insurance programs for co-insurance payments due from Medicaid-eligible patients with primary coverage under the Medicare program. Some Medicaid programs also pay for additional services, including some oral medications that are not covered by Medicare. We are enrolled in the Medicaid programs in the states in which we conduct our business.

Commercial revenue

Before a patient becomes eligible to elect to have Medicare as their primary payor for dialysis services, a patient’s commercial insurance plan, if any, is generally responsible for payment of such dialysis services for up to the first 33 months, as discussed above. Although commercial payment rates vary, average commercial payment rates established under commercial contracts are generally significantly higher than Medicare rates. The payments we receive from commercial payors generate nearly all of our profits. Payment methods from commercial payors can include a single lump-sum per treatment, referred to as bundled rates, or in other cases separate payments for dialysis treatments and pharmaceuticals, if used as part of the treatment, referred to as Fee-for-Service (FFS) rates. Commercial payment rates are the result of negotiations between us and insurers or third-party administrators. Our out-of-network payment rates are on average higher than in-network commercial contract payment rates. We continue to enter into some commercial contracts, covering certain patients that will primarily pay us under a single bundled payment rate for all dialysis services provided to these patients. However, some contracts will pay us for certain other services and pharmaceuticals in addition to the bundled payment. These contracts typically contain annual price escalator provisions. We are continuously in the process of negotiating agreements with our commercial payors and if our negotiations result in overall commercial contract payment rate reductions in excess of our commercial contract payment rate increases, or if commercial payors implement plans that restrict access to coverage or the duration or breadth of benefits or impose restrictions or limitations on patient access to commercial plans on non-contracted or out-of-network providers, it could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition. In addition, if there is an increase in job losses in the U.S., or depending upon changes to the healthcare regulatory system by CMS and/or the impact of healthcare insurance exchanges, we could experience a decrease in the number of patients covered under commercial insurance plans and/or an increase in uninsured or underinsured patients. Patients with commercial insurance who cannot otherwise maintain coverage frequently rely on financial assistance from charitable organizations, such as the American Kidney Fund. If these patients are unable to obtain or continue to receive or receive for a limited duration such financial assistance, or if our assumptions about how patients will respond to any change in such financial assistance are incorrect, it could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition.

7

Approximately 28% of our dialysis services revenues and approximately 10.5% of our dialysis patients are associated with non-acute commercial payors for the year ended December 31, 2017. Non-acute commercial patients as a percentage of our total dialysis patients for 2017 decreased 1.4% as compared to 2016. Less than 1% of our U.S. dialysis and related lab services revenues are due directly from patients. There is no single commercial payor that accounted for more than 10% of total U.S. dialysis and related lab services revenues for the year ended December 31, 2017. See Note 23 to the consolidated financial statements included in this report for disclosure on our concentration related to our commercial payors on a total consolidated net revenue basis.

The healthcare reform legislation enacted in 2010 introduced healthcare insurance exchanges which provide a marketplace for eligible individuals and small employers to purchase healthcare insurance. The business and regulatory environment continues to evolve as the exchanges mature, and regulations are challenged, changed and enforced. If commercial payor participation in the exchanges continues to decrease, it could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition. Although we cannot predict the short- or long-term effects of these factors, we believe the healthcare insurance exchanges could result in a reduction in ESRD patients covered by traditional commercial insurance policies and an increase in the number of patients covered through the exchanges under more restrictive commercial plans with lower reimbursement rates or higher deductibles and co-payments that patients may not be able to pay. To the extent that the ongoing implementation of such exchanges or changes in statutes or regulations, or enforcement of statutes or regulations regarding the exchanges results in a reduction in reimbursement rates for our services from commercial and/or government payors, it could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition.

In addition, in December 2016, CMS published an interim final rule that questioned the use of charitable premium assistance for ESRD patients and would have established new conditions for coverage standards for dialysis facilities. In January 2017, a federal court issued a preliminary injunction on CMS’ interim final rule and in June 2017, at the request of CMS, the court stayed the proceedings while CMS pursues new rulemaking options. In November 2017, when CMS published the 2018 final rule that updates payment policies and rates under the ESRD PPS, and the 2019 proposed Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters, it did not pursue further discussion or rule making related to charitable premium assistance or propose changes to historical charitable premium assistance guidelines. This does not preclude CMS or another regulatory agency or legislative authority from issuing a new rule or guidance that challenges charitable premium assistance. Additionally, any other law, rule, or guidance issued by CMS or other regulatory or legislative authorities restricting or prohibiting the ability of patients with access to alternative coverage from selecting a marketplace plan on or off exchange, and/or otherwise restricting or prohibiting the use of charitable premium assistance, could adversely impact dialysis centers across the U.S. making certain centers economically unviable, restrict the ability of dialysis patients to obtain and maintain optimal insurance coverage, and have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations, and financial condition.

Revenue from other pharmaceuticals and EPO

The impact of physician-prescribed pharmaceuticals on our overall revenues that are separately billable has significantly decreased since Medicare’s single bundled payment system went into effect beginning in January 2011, as well as some additional commercial contracts that pay us a single bundled payment rate. Approximately 2% of our total U.S. dialysis and related lab services net patient services revenues for the years ended December 31, 2017 and 2016, are associated with the administration of separately-billable physician-prescribed pharmaceuticals. Of this, the administration of EPO that was separately billable, accounted for approximately half of our separately billable pharmaceuticals of our U.S. dialysis and related lab services business for both years. EPO is produced by a single manufacturer, Amgen USA Inc. (Amgen). In 2017, we entered into a Sourcing and Supply Agreement with Amgen that expires on December 31, 2022. Under the terms of the agreement, we will purchase EPO in amounts necessary to meet no less than 90% of our requirements for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) through the expiration of the contract. The actual amount of EPO that we will purchase from Amgen will depend upon the amount of EPO administered during dialysis treatments as prescribed by physicians and the overall number of patients that we serve. Any interruption in the supply of EPO or product cost increases that we are unable to mitigate could materially impact our operations.

In addition to EPO, other drugs are included in and, in the future, other drugs will be added to the ESRD PPS. On January 1, 2018, calcimimetics, a drug class taken by many ESRD patients to treat mineral bone disease, became part of the ESRD PPS. The drug has both an oral form (Sensipar) and IV form (Parsabiv). Because the IV form is a new injectable for which there is no current functional category, neither Parsabiv nor Sensipar are considered accounted for in the ESRD PPS base rate and are reimbursed through a Transitional Drug Add-on Payment Adjustment (TDAPA). The TDAPA period is expected to continue for a period of two years. Currently, the oral and IV forms of the drug are produced and sold by a single manufacturer, Amgen. In December 2017, we entered into a Sourcing and Supply Agreement with Amgen for both the oral and IV versions of calcimimetics. Our operating results could be materially impacted by certain factors, including physician prescribing patterns, vendor contracts with Amgen and other suppliers, the timing of the entry into the market of a generic oral equivalent, whether

8

the drug enters into the ESRD PPS and becomes part of its bundled payment following TDAPA and, if so, at what rate, and how commercial payors will treat reimbursement of the drug.

Physician relationships

An ESRD patient generally seeks treatment at an outpatient dialysis center near his or her home where his or her treating nephrologist has practice privileges. Our relationships with local nephrologists and our ability to meet their needs and the needs of their patients are key factors in the success of our dialysis operations. Approximately 5,300 nephrologists currently refer patients to our outpatient dialysis centers. As is typical in the dialysis industry, one or a few physicians, including the outpatient dialysis center’s medical director, usually account for all or a significant portion of an outpatient dialysis center’s patient base.

Participation in the Medicare ESRD program requires that dialysis services at an outpatient dialysis center be under the general supervision of a medical director who is a licensed physician. We have engaged physicians or groups of physicians to serve as medical directors for each of our outpatient dialysis centers. At some outpatient dialysis centers, we also separately contract with one or more other physicians to serve as assistant or associate medical directors or to direct specific programs, such as home dialysis training programs. We have approximately 1,000 individual physicians and physician groups under contract to provide medical director services.

Medical directors for our dialysis centers enter into written contracts with us that specify their duties and fix their compensation generally for periods of ten years. The compensation of our medical directors is the result of arm’s length negotiations and generally depends upon an analysis of various factors such as the physician’s duties, responsibilities, professional qualifications and experience, among others.

Our medical director contracts for our dialysis centers generally include covenants not to compete. Also, except as described below, when we acquire an outpatient dialysis center from one or more physicians or where one or more physicians own minority interests in our outpatient dialysis centers, these physicians have agreed to refrain from owning interests in other competing outpatient dialysis centers within a defined geographic area for various time periods. These non-compete agreements restrict the physicians from owning or providing medical director services to other outpatient dialysis centers, but do not prohibit the physicians from referring patients to any outpatient dialysis center, including competing centers. Many of these non-compete agreements continue for a period of time beyond expiration of the corresponding medical director agreements, although some expire at the same time as the medical director agreement. Occasionally, we experience competition from a new outpatient dialysis center established by a former medical director following the termination of his or her relationship with us. As part of our Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA), as described below, we also have agreed not to enforce investment non-compete restrictions relating to dialysis clinics or programs that were established pursuant to a partial divestiture joint venture transaction. Therefore, to the extent a joint venture partner or medical director has a contract(s) with us covering dialysis clinics or programs that were established pursuant to a partial divestiture, we will not enforce the investment non-compete provision relating to those clinics and/or programs.

If a significant number of physicians, including an outpatient dialysis center’s medical directors, were to cease referring patients to our outpatient dialysis centers, it would have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition.

Government regulation

Our dialysis operations are subject to extensive federal, state and local governmental laws and regulations. These laws and regulations require us to meet various standards relating to, among other things, government payment programs, dialysis facilities and equipment, management of centers, personnel qualifications, maintenance of proper records, and quality assurance programs and patient care.

If any of our operations are found to violate applicable laws or regulations, we could suffer severe consequences that could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations, financial condition and stock price, including:

• | Suspension or termination of our participation in government payment programs; |

• | Refund amounts received in violation of law or applicable payment program requirements; |

• | Loss of required government certifications or exclusion from government payment programs; |

• | Loss of licenses required to operate healthcare facilities or administer pharmaceuticals in some of the states in which we operate or elsewhere; |

9

• | Reductions in payment rates or coverage for dialysis and ancillary services and related pharmaceuticals; |

• | Civil or criminal liability, fines, damages and monetary penalties for violations of healthcare fraud and abuse laws, including the federal Anti-Kickback Statute contained in the Social Security Act of 1935, as amended (Anti-Kickback Statute), Stark Law and False Claims Act (FCA), and other failures to meet regulatory requirements; |

• | Enforcement actions by governmental agencies and/or claims for monetary damages from patients who believe their protected health information (PHI) has been used, disclosed or not properly safeguarded in violation of federal or state patient privacy laws including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the Privacy Act of 1974; |

• | Mandated changes to our practices or procedures that significantly increase operating expenses; |

• | Imposition of and compliance with corporate integrity agreements that could subject us to ongoing audits and reporting requirements as well as increased scrutiny of our billing and business practices and potential fines; |

• | Termination of relationships with medical directors; and |

• | Harm to our reputation which could impact our business relationships, affect our ability to obtain financing and decrease access to new business opportunities, among other things. |

We expect that our industry will continue to be subject to substantial regulation, the scope and effect of which are difficult to predict. Our activities could be reviewed or challenged by regulatory authorities at any time in the future. This regulation and scrutiny could have a material adverse impact on us.

Licensure and certification

Our dialysis centers are certified by CMS, as is required for the receipt of Medicare payments. In some states, our outpatient dialysis centers also are required to secure additional state licenses and permits. Governmental authorities, primarily state departments of health, periodically inspect our centers to determine if we satisfy applicable federal and state standards and requirements, including the conditions of participation in the Medicare ESRD program.

To date, we have experienced some delays in obtaining Medicare certifications from CMS. Recent legislation will allow private entities to perform initial dialysis facilities certifications beginning in 2019. We may choose to use these private companies in the future, although the number of companies who will enter the market and the cost of surveys they might perform has yet to be determined.

Federal Anti-Kickback Statute

The federal Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits, among other things, knowingly and willfully offering, paying, soliciting or receiving remuneration, directly or indirectly, in cash or kind, to induce or reward either the referral of an individual for, or the purchase, or order or recommendation of, any good or service, for which payment may be made under federal and state healthcare programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.

Federal criminal penalties for the violation of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute include imprisonment, fines and exclusion of the provider from future participation in the federal healthcare programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Violations of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute are punishable by imprisonment for up to ten years and fines of up to $100,000 or both. Larger fines can be imposed upon corporations under the provisions of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines and the Alternate Fines Statute. Individuals and entities convicted of violating the federal Anti-Kickback Statute are subject to mandatory exclusion from participation in Medicare, Medicaid and other federal healthcare programs for a minimum of five years. Civil penalties for violation of this law include up to $100,000 in monetary penalties per violation, repayments of up to three times the total payments between the parties and suspension from future participation in Medicare and Medicaid. Court decisions have held that the statute may be violated even if only one purpose of remuneration is to induce referrals. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, as amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Affordable Care Act (ACA)) amended the federal Anti-Kickback Statute to clarify the intent that is required to prove a violation. Under the statute as amended, the defendant does not need to have actual knowledge of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute or have the specific intent to violate it. In addition, the ACA amended the federal Anti-Kickback Statute to provide that any claims for items or services resulting from a violation of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute are considered false or fraudulent for purposes of the FCA.

10

The federal Anti-Kickback Statute includes statutory exceptions and regulatory safe harbors that protect certain arrangements. Business transactions and arrangements that are structured to comply fully with an applicable safe harbor do not violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute. However, transactions and arrangements that do not satisfy all elements of a relevant safe harbor do not necessarily violate the law. When an arrangement does not satisfy a safe harbor, the arrangement must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis in light of the parties’ intent and the arrangement’s potential for abuse. Arrangements that do not satisfy a safe harbor may be subject to greater scrutiny by enforcement agencies.

We enter into several arrangements with physicians that potentially implicate the Anti-Kickback Statute, such as:

Medical Director Agreements. Because our medical directors refer patients to our dialysis centers, our arrangements with these physicians are designed to substantially comply with the safe harbor for personal service arrangements. Although the Medical Director Agreements we enter into with physicians substantially comply with the safe harbor for personal service arrangements, including the requirement that compensation be consistent with fair market value, the safe harbor requires that when services are provided on a part-time basis, the agreement must specify the schedule of intervals of services, and their precise length and the exact charge for such services. Because of the nature of our medical directors’ duties, it is impossible to fully satisfy this technical element of the safe harbor. We believe that our fair market value arrangements with physicians who serve as medical directors do not violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute; however, these arrangements could be subject to scrutiny since they do not expressly describe the schedule of part-time services to be provided under the arrangement.

Joint Ventures. We own a controlling interest in numerous U.S. dialysis related joint ventures. For the year ended December 31, 2017, these joint ventures represented approximately 24% of our net U.S. dialysis and related lab services revenues. We may continue to increase the number of our joint ventures. Our relationships with physicians and other referral sources relating to these joint ventures do not fully satisfy the safe harbor for investments in small entities. Although failure to comply with a safe harbor does not render an arrangement illegal under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, an arrangement that does not operate within a safe harbor may be subject to scrutiny and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) has warned in the past that certain joint venture relationships have a potential for abuse. Based upon the foregoing, physician joint ventures that fall outside the safe harbors are not, by definition, prohibited by law. Instead, such joint ventures require case-by-case evaluation under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute.

In this regard, we have structured our joint ventures to satisfy as many elements of the safe harbor for investments in small entities as we believe are commercially reasonable. For example, we believe that these investments are offered and made by us on a fair market value basis and provide returns to the investors in proportion to their actual investment in the venture. We believe that our joint venture arrangements do not violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute; however, since the arrangements do not satisfy all of the requirements of an applicable safe harbor, these arrangements could be subject to challenge on the ground that they are intended to induce patient referrals. In that regard, we were subject to investigation by the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Colorado, the Civil Division of the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and the OIG related to our relationships with physicians, including our joint ventures, and whether those relationships and joint ventures comply with the federal Anti-Kickback Statute and the FCA. In October 2014, we entered into a Settlement Agreement with the United States and relator David Barbetta to resolve the then pending 2010 and 2011 U.S. Attorney physician relationship investigations. In connection with the resolution of this matter, and in exchange for the OIG’s agreement not to exclude us from participating in the federal healthcare programs, we have entered into a five-year CIA with the OIG. The CIA (i) requires that we maintain certain elements of our compliance programs; (ii) imposes certain expanded compliance-related requirements during the term of the CIA; (iii) requires ongoing monitoring and reporting by an independent monitor, imposes certain reporting, certification, records retention and training obligations, allocates certain oversight responsibility to the Board’s Compliance Committee, and necessitates the creation of a Management Compliance Committee and the retention of an independent compliance advisor to the Board; and (iv) contains certain business restrictions related to a subset of our joint venture arrangement. The costs associated with compliance with the CIA could be substantial and may be greater than we currently anticipate. In addition, in the event of a breach of the CIA, we could become liable for payment of certain stipulated penalties, and could be excluded from participation in federal healthcare programs.

Lease Arrangements. We lease space for numerous dialysis centers from entities in which physicians, hospitals or medical groups hold ownership interests, and we sublease space to referring physicians at approximately 250 of our dialysis centers as of December 31, 2017. We believe that these arrangements comply with the federal Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbor for space rentals in all material respects. Therefore, we believe that these lease arrangements should not be subject to challenge under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute.

Common Stock. Some medical directors and other referring physicians may own our common stock. We believe that these interests materially satisfy the requirements of the Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbor for investments in large publicly traded companies. Therefore, we believe that these investments should not be subject to challenge under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute.

11

Discounts. Our dialysis centers sometimes acquire certain items and services at a discount that may be reimbursed by a federal healthcare program. We believe that our vendor contracts that include discount or rebate provisions are in compliance with the federal Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbor for discounts, and accordingly, we believe that our discounted vendor contracts should not be subject to challenge under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute.

If any of our business transactions or arrangements, including those described above, were found to violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, we, among other things, could face criminal, civil or administrative sanctions, including possible exclusion from participation in Medicare, Medicaid and other state and federal healthcare programs. Any findings that we have violated these laws could have a material adverse impact on our business, results of operations, financial condition and stock price.

Stark Law

The Stark Law prohibits a physician who has a financial relationship, or who has an immediate family member who has a financial relationship, with entities providing Designated Health Services (DHS), from referring Medicare and Medicaid patients to such entities for the furnishing of DHS, unless an exception applies. DHS is defined to mean any of the following enumerated items or services; clinical laboratory services; physical therapy services; occupational therapy services; radiology services, including magnetic resonance imaging, computerized axial tomography scans, and ultrasound services; radiation therapy services and supplies; durable medical equipment and supplies; parenteral and enteral nutrients, equipment, and supplies; prosthetics, orthotics and prosthetic devices and supplies; home health services; outpatient prescription drugs; inpatient and outpatient hospital services; and outpatient speech-language pathology services. The types of financial arrangements between a physician and a DHS entity that trigger the self-referral prohibitions of the Stark Law are broad and include direct and indirect ownership and investment interests and compensation arrangements. The Stark Law also prohibits the DHS entity receiving a prohibited referral from presenting, or causing to be presented, a claim or billing for the services arising out of the prohibited referral. The prohibition applies regardless of the reasons for the financial relationship and the referral; unlike the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, intent to induce referrals is not required. If the Stark Law is implicated, the financial relationship must fully satisfy a Stark Law exception. If an exception is not satisfied, then the arrangement could be subject to sanctions. Sanctions for violation of the Stark Law include denial of payment for claims for services provided in violation of the prohibition, refunds of amounts collected in violation of the prohibition, a civil penalty of up to $15,000 for each service arising out of the prohibited referral, a civil penalty of up to $100,000 against parties that enter into a scheme to circumvent the Stark Law prohibition, civil assessment of up to three times the amount claimed, and potential exclusion from the federal healthcare programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Amounts collected for prohibited claims must be reported and refunded generally within 60 days after the date on which the overpayment was identified. Furthermore, Stark Law violations and failure to return overpayments timely can form the basis for FCA liability as discussed below.

The definition of DHS under the Stark Law excludes services paid under a composite rate, even if some of the components bundled in the composite rate are DHS. Although the ESRD bundled payment system is no longer titled a composite rate, we believe that the former composite rate payment system and the current bundled system are both composite systems excluded from the Stark Law. Since most services furnished to Medicare beneficiaries provided in our dialysis centers are reimbursed through a bundled rate, the services performed in our facilities generally are not DHS, and the Stark Law referral prohibition does not apply to those services. Certain separately billable drugs (drugs furnished to an ESRD patient that are not for the treatment of ESRD that CMS allows our centers to bill for using the so-called AY modifier) may be considered DHS. However, for compliance with the law we have implemented certain billing controls to limit DHS being billed out of our dialysis clinics. Likewise, the definition of inpatient hospital services, for purposes of the Stark Law, also excludes inpatient dialysis performed in hospitals that are not certified to provide ESRD services. Consequently, our arrangements with such hospitals for the provision of dialysis services to hospital inpatients do not trigger the Stark Law referral prohibition.

In addition, although prescription drugs are DHS, there is an exception in the Stark Law for EPO and other specifically enumerated dialysis drugs when furnished in or by an ESRD facility such that the arrangement for the furnishing of the drugs does not violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, and all billing and claims submission for the drugs does not violate any laws or regulations governing billing or claims submission. The exception is available only for drugs included on a list of Current Procedural Terminology/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (CPT/HCPCS) codes published by CMS, and for EPO, Aranesp® and equivalent drugs dispensed by the ESRD facility for use at home. While we believe that most drugs furnished by our dialysis centers are covered by the exception, dialysis centers may administer drugs that are not on the list of CPT/HCPCS codes and therefore do not meet this exception. In order for a physician who has a financial relationship with a dialysis center to order one of these drugs from the center and for the center to obtain Medicare reimbursement, another exception must apply.

We have entered into several types of financial relationships with referring physicians, including compensation arrangements. If our dialysis centers were to bill for a non-exempted drug and the financial relationships with the referring

12

physician did not satisfy an exception, we could in the future be required to change our practices, face civil penalties, pay substantial fines, return certain payments received from Medicare and beneficiaries or otherwise experience a material adverse effect as a result of a challenge to payments made pursuant to referrals from these physicians under the Stark Law.

Medical Director Agreements. We believe that our medical director agreements satisfy the personal services arrangement exception to the Stark Law. While we believe that the compensation provisions included in our medical director agreements are the result of arm’s length negotiations and result in fair market value payments for medical director services, an enforcement agency could nevertheless challenge the level of compensation that we pay our medical directors.

Lease Agreements. Some of our dialysis centers are leased from entities in which referring physicians hold interests and we sublease space to referring physicians at some of our dialysis centers. The Stark Law provides an exception for lease arrangements if specific requirements are met. We endeavor to structure our leases and subleases with referring physicians to satisfy the requirements for this exception.

Common Stock. Some medical directors and other referring physicians may own our common stock. We believe that these interests satisfy the Stark Law exception for investments in large publicly traded companies.

Joint Ventures. Some of our referring physicians also own equity interests in entities that operate our dialysis centers. None of the Stark Law exceptions applicable to physician ownership interests in entities to which they make DHS referrals apply to the kinds of ownership arrangements that referring physicians hold in several of our subsidiaries that operate dialysis centers. Accordingly, these dialysis centers do not bill Medicare for DHS referrals from physician owners. If the dialysis centers bill for DHS referred by physician owners, the dialysis center would be subject to the Stark Law penalties described above.

Other Operations. The operations of our ancillary and subsidiary businesses are also subject to compliance with the Stark Law, and any failure to comply with these requirements, particularly in light of the strict liability nature of the Stark Law, could subject these operations to the Stark Law penalties and sanctions described above.

While we believe that most of our operations do not implicate the Stark Law, particularly under the ESRD bundled payment system, and that to the extent that our dialysis centers furnish DHS, they either meet an exception or do not bill for services that do not meet a Stark Law exception, if CMS determined that we have submitted claims in violation of the Stark Law, or otherwise violated the Stark Law, we would be subject to the penalties described above. In addition, it might be necessary to restructure existing compensation agreements with our medical directors and to repurchase or to request the sale of ownership interests in subsidiaries and partnerships held by referring physicians or, alternatively, to refuse to accept referrals for DHS from these physicians, or take other actions to modify our operations. Any such penalties and restructuring or other required actions could have a material adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition.

Fraud and abuse under state law

Many states in which we operate dialysis centers have statutes prohibiting physicians from holding financial interests in various types of medical facilities to which they refer patients. Some of these statutes could potentially be interpreted broadly as prohibiting physicians who hold shares of our publicly traded stock from referring patients to our dialysis centers if the centers use our laboratory subsidiary to perform laboratory services for their patients. States also have laws similar to or stricter than the federal Anti-Kickback Statute that may affect our ability to receive referrals from physicians with whom we have financial relationships, such as our medical directors. Some state anti-kickback statutes also include civil and criminal penalties. Some of these statutes include exemptions that may be applicable to our medical directors and other physician relationships or for financial interests limited to shares of publicly traded stock. Some, however, include no explicit exemption for medical director services or other services for which we contract with and compensate referring physicians or for joint ownership interests of the type held by some of our referring physicians or for financial interests limited to shares of publicly traded stock. If these statutes are interpreted to apply to referring physicians with whom we contract for medical director and similar services, to referring physicians with whom we hold joint ownership interests or to physicians who hold interests in DaVita Inc. limited solely to our publicly traded stock, we may be required to terminate or restructure some or all of our relationships with or refuse referrals from these referring physicians and could be subject to criminal, civil and administrative sanctions, refund requirements and exclusions from government healthcare programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Such events could negatively affect the decision of referring physicians to refer patients to our centers.

13

The False Claims Act

The federal FCA is a means of policing false bills or false requests for payment in the healthcare delivery system. In part, the FCA authorizes the imposition of up to three times the government’s damages and civil penalties on any person who, among other acts:

• | Knowingly presents or causes to be presented to the federal government, a false or fraudulent claim for payment or approval; |

• | Knowingly makes, uses or causes to be made or used, a false record or statement material to a false or fraudulent claim; |

• | Knowingly makes, uses, or causes to be made or used, a false record or statement material to an obligation to pay the government, or knowingly conceals or knowingly and improperly, avoids or decreases an obligation to pay or transmit money or property to the federal government; or |

• | Conspires to commit the above acts. |

In addition, amendments to the FCA impose severe penalties for the knowing and improper retention of overpayments collected from government payors. Under these provisions, within 60 days of identifying an overpayment, a provider is required to notify CMS or the Medicare Administrative Contractor of the overpayment and the reason for it and return the overpayment. An overpayment impermissibly retained could subject us to liability under the FCA, exclusion, and penalties under the federal Civil Monetary Penalty statute. As a result of these provisions, our procedures for identifying and processing overpayments may be subject to greater scrutiny. We have made significant investments to accelerate the time it takes us to identify and process overpayments and we may be required to make additional investments in the future. Acceleration in our ability to identify and process overpayments could result in us refunding overpayments to government or other payors sooner than we have in the past. A significant acceleration of these refunds could have a material adverse effect on our operating cash flows.

The penalties for a violation of the FCA range from $5,500 to $11,000 (adjusted for inflation) for each false claim, plus up to three times the amount of damages caused by each false claim, which can be as much as the amounts received directly or indirectly from the government for each such false claim. On February 3, 2017, the DOJ issued a final rule announcing adjustments to FCA penalties, under which the per claim penalty range increases to $10,957 to $21,916 for penalties assessed after February 3, 2017, so long as the underlying conduct occurred after November 2, 2015. The federal government has used the FCA to prosecute a wide variety of alleged false claims and fraud allegedly perpetrated against Medicare and state healthcare programs, including coding errors, billing for services not rendered, the submission of false cost reports, billing for services at a higher payment rate than appropriate, billing under a comprehensive code as well as under one or more component codes included in the comprehensive code and billing for care that is not considered medically necessary. The ACA provides that claims tainted by a violation of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute are false for purposes of the FCA. Some courts have held that filing claims or failing to refund amounts collected in violation of the Stark Law can form the basis for liability under the FCA. In addition to the provisions of the FCA, which provide for civil enforcement, the federal government can use several criminal statutes to prosecute persons who are alleged to have submitted false or fraudulent claims for payment to the federal government.

Privacy and Security

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and its implementing privacy and security regulations, as amended by the federal Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), (collectively referred to as HIPAA), require us to provide certain protections to patients and their health information. The HIPAA privacy and security regulations extensively regulate the use and disclosure of PHI and require covered entities, which include healthcare providers, to implement and maintain administrative, physical and technical safeguards to protect the security of such information. Additional security requirements apply to electronic PHI. These regulations also provide patients with substantive rights with respect to their health information.

The HIPAA privacy and security regulations also require us to enter into written agreements with certain contractors, known as business associates, to whom we disclose PHI. Covered entities may be subject to penalties for, among other activities, failing to enter into a business associate agreement where required by law or as a result of a business associate violating HIPAA if the business associate is found to be an agent of the covered entity and acting within the scope of the agency. Business associates are also directly subject to liability under the HIPAA privacy and security regulations. In instances

14

where we act as a business associate to a covered entity, there is the potential for additional liability beyond our status as a covered entity.

Covered entities must report breaches of unsecured PHI to affected individuals without unreasonable delay but not to exceed 60 days of discovery of the breach by a covered entity or its agents. Notification must also be made to the HHS, and, for breaches of unsecured PHI involving more than 500 residents of a state or jurisdiction, to the media. All non-permitted uses or disclosures of unsecured PHI are presumed to be breaches unless the covered entity or business associate establishes that there is a low probability the information has been compromised. Various state laws and regulations may also require us to notify affected individuals in the event of a data breach involving individually identifiable information without regard to whether there is a low probability of the information being compromised.

Penalties for impermissible use or disclosure of PHI were increased by the HITECH Act by imposing tiered penalties of more than $50,000 per violation and up to $1.5 million per year for identical violations. In addition, HIPAA provides for criminal penalties of up to $250,000 and ten years in prison, with the severest penalties for obtaining and disclosing PHI with the intent to sell, transfer or use such information for commercial advantage, personal gain or malicious harm. Further, state attorneys general may bring civil actions seeking either injunction or damages in response to violations of the HIPAA privacy and security regulations that threaten the privacy of state residents. We believe our HIPAA Privacy and Security Program sufficiently addresses HIPAA and state privacy law requirements.

Healthcare reform

In March 2010, broad healthcare reform legislation was enacted in the U.S. through the ACA. Although many of the provisions of the ACA did not take effect immediately and continue to be implemented, and some have been and may be modified before or during their implementation, the reforms could have an impact on our business in a number of ways. We cannot predict how employers, private payors or persons buying insurance might react to federal and state healthcare reform legislation or what form many of these regulations will take before implementation.

The ACA introduced healthcare insurance exchanges, which provide a marketplace for eligible individuals and small employers to purchase healthcare insurance. The business and regulatory environment continues to evolve as the exchanges mature, and statutes and regulations are challenged, changed and enforced.

The ACA also requires that all non-grandfathered individual and small group health plans sold in a state, including plans sold through the state-based exchanges created pursuant to the healthcare reform laws, cover essential health benefits (EHBs) in ten general categories. The scope of the benefits is intended to equal the scope of benefits under a typical employer plan.

On February 25, 2013, HHS issued the final rule governing the standards applicable to EHB benchmark plans, new definitions, actuarial value requirements and methodology, and published a list of plan benchmark options that states can use to develop EHBs. The rule describes specific coverage requirements that (i) prohibit discrimination against individuals because of pre-existing or chronic conditions on health plans applicable to EHBs, (ii) ensure network adequacy of essential health providers, and (iii) prohibit benefit designs that limit enrollment and that prohibit access to care for enrollees. Subsequent regulations relevant to the EHB have continued the benchmark plan approach for 2016 and future years and have implemented clarifications and modifications to the existing EHB regulations, including the prohibition on discrimination, network adequacy standards and other requirements. In recent years, CMS has issued an annual Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters rulemaking and related guidance setting forth standards for insurance plans provided through the exchanges.

Other aspects of the 2010 healthcare reform laws may affect our business as well, including changes affecting the Medicare and Medicaid programs. We note, however, that the 2016 Presidential and Congressional elections and subsequent developments have caused the future state of the exchanges and other ACA reforms to be very unclear. The Republicans, who now control the Administration and Congress, have repeatedly expressed a desire to repeal and replace the ACA. Further, in October 2017, the federal government announced that cost-sharing reduction payments to insurers would end, effective immediately, unless Congress appropriated the funds, and, in December 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which includes a provision that eliminates the penalty under the ACA’s individual mandate and could impact the future state of the exchanges. Moreover, in February 2018, Congress passed the BBA which, among other things, repealed the Independent Payment Advisory Board that was established by the ACA and intended to reduce the rate of growth in Medicare spending. While certain provisions of the BBA may increase the scope of benefits available for certain chronically ill Federal health care program beneficiaries beginning in 2020, the ultimate impact of such changes cannot be predicted. While there may be significant changes to the healthcare environment in the future, the specific changes and their timing are not yet apparent. As a result, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the future with respect to the exchanges, and, indeed, many core aspects of the current health care marketplace. While specific changes and their timing are not yet apparent, the enacted reforms as well as

15

future legislative, regulatory, and executive changes could have a material adverse effect on our results of operations, including lowering our reimbursement rates and/or increasing our expenses.

Other regulations

Our U.S. dialysis and related lab services operations are subject to various state hazardous waste and non-hazardous medical waste disposal laws. These laws do not classify as hazardous most of the waste produced from dialysis services. Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations require employers to provide workers who are occupationally subject to blood or other potentially infectious materials with prescribed protections. These regulatory requirements apply to all healthcare facilities, including dialysis centers, and require employers to make a determination as to which employees may be exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials and to have in effect a written exposure control plan. In addition, employers are required to provide or employ hepatitis B vaccinations, personal protective equipment and other safety devices, infection control training, post-exposure evaluation and follow-up, waste disposal techniques and procedures and work practice controls. Employers are also required to comply with various record-keeping requirements. We believe that we are in material compliance with these laws and regulations.

A few states have certificate of need programs regulating the establishment or expansion of healthcare facilities, including dialysis centers. We believe that we are in material compliance with all applicable state certificate of need laws.

Capacity and location of our U.S. dialysis centers