Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EX-10.1(A) - EXHIBIT 10.1(A) - Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics, Inc. | brhc10024430_ex10-1a.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 8-K

CURRENT REPORT

Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 6, 2021

BROOKLYN IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS, INC.

(Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter)

|

Delaware

|

001-11460

|

31-1103425

|

|

(State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation)

|

(Commission File Number)

|

(IRS Employer Identification No.)

|

|

140 58th Street, Building A, Suite 2100

|

||

|

Brooklyn, New York

|

11220

|

|

|

(Address of Principal Executive Offices)

|

(Zip Code)

|

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 582-1199

Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the

following provisions:

| ☐ |

Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425)

|

| ☐ |

Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12)

|

|

☐

|

Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b))

|

|

☐

|

Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c))

|

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

|

Title of each class

|

Trading symbol

|

Name of each exchange on which registered

|

||

|

Common Stock, par value $0.005 per share

|

BTX

|

NYSE American

|

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934:

Emerging growth company ☐

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards

provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

| Item 5.02. |

Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Certain Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers.

|

Appointment of Erich Mohr as Director

On May 6, 2021, the board of directors elected Erich Mohr, Ph.D, to serve as a member of the board, with a term effective on May 7, 2021 and continuing

until our 2021 annual meeting of stockholders. It is expected that Dr. Mohr will be appointed to the board’s compensation committee.

Dr. Mohr serves as the Chairman of Oak Bay Biosciences Inc., a developmental biotechnology company focused on treatments for Stargardt disease. Since 2006

Dr. Mohr has been the founder, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of MedGenesis Therapeutix Inc., a biopharmaceutical company that commercializes treatments for Parkinson’s disease. From 2002 to 2005, Dr. Mohr served as the Executive Vice

President and Chief Scientific Officer of PRA International, a clinical research organization that provided drug development services to pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. From 1995 to 2002, Dr. Mohr was the founder, Chairman and Chief

Executive Officer of CroMedica International, which later merged with PRA International. Dr. Mohr received a MSc and Ph.D from University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, and a BA and BSc from University of the Pacific. He is 67 years old.

There are no family relationships between Dr. Mohr and any of our existing directors or our executive officers, and Dr. Mohr has not had any direct or

indirect material interest in any transaction required to be disclosed pursuant to Item 404(a) of Regulation S-K under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

Resignation of Yiannis Monovoukas as Director

On May 6, 2021, Yiannis Monovoukas notified the board of directors of his intention to resign as a director effective in connection with the board’s

identification and election of an additional new director. Mr. Monovoukas’s resignation as a director was effective as of May 7, 2021, upon the appointment of Erich Mohr to the board.

The resignation of Mr. Monovoukas was not the result of any disagreement relating to our operations, policies or practices.

2

| Item 8.01 |

Other Events.

|

In the discussions below, “Brooklyn Inc.” refers to Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics, Inc. (formerly known as NTN Buzztime, Inc.) and “Brooklyn LLC” refers to Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics LLC, a wholly

owned subsidiary of Brooklyn Inc. All references to “our company,” “we,” “us” or “our” mean Brooklyn Inc. and its subsidiaries, including Brooklyn LLC, unless stated otherwise or the context otherwise requires.

On March 25, 2021, BIT Merger Sub, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Brooklyn Inc. (then known as NTN Buzztime, Inc.) merged with and into Brooklyn LLC, with Brooklyn LLC surviving as a wholly

owned subsidiary of Brooklyn Inc.. This transaction, which we refer to as the Merger, was completed in accordance with the terms of an agreement and plan of merger and reorganization dated August 12, 2020, or the Merger Agreement, among Brooklyn

Inc. (then known as NTN Buzztime, Inc.), BIT Merger Sub, Inc. and Brooklyn LLC.

On March 26, 2021, Brooklyn Inc. sold its rights, title and interest in and to the assets relating to the business it operated prior to the Merger, which it had operated under the name “NTN

Buzztime, Inc.,” to eGames.com Holdings LLC, or eGames.com, in exchange for eGames.com’s payment of a purchase price of $2.0 million and assumption of specified liabilities relating to such pre-Merger business. This transaction, which we refer to

as the Asset Sale, was completed in accordance with the terms of an asset purchase agreement dated September 18, 2020, as amended, or the Asset Purchase Agreement, between Brooklyn Inc. and eGames.com.

Following the completion of the Merger and the Asset Sale, our business consists exclusively of the business conducted by our wholly owned subsidiary Brooklyn LLC.

Business of Brooklyn LLC

We are a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on exploring the role that cytokine-based therapy can have on the immune system in treating patients with cancer,

both as a single agent and in combination with other anti-cancer therapies. We are seeking to develop IRX‑2, a novel cytokine-based therapy, to treat patients with cancer. IRX‑2 active constituents, namely Interleukin-2, or IL‑2, and other key

cytokines, are postulated to signal, enhance and restore immune function suppressed by the tumor, thus enabling the immune system to attack cancer cells, unlike existing cancer therapies, which rely on targeting the cancer directly. We also are

exploring opportunities to advance oncology, blood disorder, and monogenic disease therapies using gene-editing cell‑therapy technology through a license with Factor Biosciences Limited and Novellus Therapeutics Limited, which we refer to

collectively as the Licensor.

The development of our product candidates could be disrupted and materially adversely affected by the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of measures imposed by the

governments in affected regions, businesses and schools have been suspended due to quarantines intended to contain this outbreak. The spread of SARS CoV‑2 from China to other countries resulted in the Director General of the World Health

Organization declaring COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020. While the constraints of the pandemic are slowly being lifted, we are still assessing the longer term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our development plans, and on the ability to conduct

our clinical trials There can be no assurance that this analysis will enable us to avoid or remediate part or all of any impact from the spread of COVID-19 or its consequences, including downturns in business sentiment generally. The extent to

which the COVID-19 pandemic and global efforts to contain its spread will impact our operations will depend on future developments, which are highly uncertain and cannot be predicted at this time, and include the duration, severity and scope of the

pandemic and the actions taken to contain or treat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patients in our clinical trials have conditions that make them especially vulnerable to COVID-19, and as a result we have seen slowdowns in enrollment in our clinical

trials. While our Phase 2b clinical study in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, known as the INSPIRE study, is fully populated, our other clinical studies are likely to continue to encounter delays as a result of the

pandemic. Further, with respect to the INSPIRE study, we anticipate that the COVID-19 pandemic will slow our ability to close out trial sites and report trial data.

IRX‑2 is a therapy based on IL‑2, a type of cytokine-signaling molecule in the immune system. While many of the mechanisms of action of COVID-19 are still unknown, there is

evidence that for some patients, severe COVID-19 patients may result in “cytokine storm syndrome,” in which the body releases cytokines into the body too quickly, which can create symptoms such as high fever, inflammation, severe fatigue and nausea

and can lead to severe or life-threatening symptoms.

3

In June 2020 the Journal of Medical Virology published a letter submitted by Wen Luo, Jia-Wen Zhang, Wei Zhang, Yuan-Long Lin and Qi

Wang, supported by grants from the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Technology, Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, stating that, based on a review of 25 patients admitted to intensive care units with a confirmed infection of COVID-19, cytokine

storm of a number of interleukins, including IL‑2, was absent. The letter therefore suggested that the severity of COVID-19 symptoms is not directly associated with circulating levels of IL‑2. There can be no assurance, however, that further study

will bear this out or that patients treated with IRX‑2, who are already at higher risk for COVID-19 due to their underlying diagnosis, will not be adversely affected.

IRX‑2 is a primary human cell-derived biological medicinal product containing multiple active cytokine components acting as immunomodulators. It is prepared from the

supernatant of pooled allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells, known as PBMNCs, that have been stimulated using a proprietary process employing a specific population of cells and a specific mitogen.

While IRX‑2 is a cytokine mixture, one of its principal active components is IL‑2, a cytokine-signaling molecule in the immune system. IL‑2 is a protein that regulates the

activities of white blood cells (leukocytes and often lymphocytes) that are responsible for immunity. IL‑2 is part of the body’s natural response to microbial infection, and in discriminating between foreign (“non-self”) and “self,” IL‑2 mediates

its effects by binding to IL‑2 receptors, which are expressed by lymphocytes. The major sources of IL‑2 are activated CD4+ T cells and activated CD8+ T cells.

Unlike existing recombinant IL‑2 therapies, IRX‑2 is naturally derived from human blood cells. This potentially may promote better tolerance, broader targeting and a natural

molecular conformation leading to greater activity, and may permit low physiologic dosing, rather than the high doses needed in other existing IL‑2 therapies. Our ongoing development program is specifically investigating use of IRX‑2 in neoadjuvant

(pre-surgical) and adjuvant (post-operative) treatment for advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, or HNSCC. IRX‑2 has received both fast track designation and orphan drug designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, for

this indication. Potential use of our product candidate in other cancer indications is also being evaluated in several investigator-sponsored trials. Finally, we are currently modifying our manufacturing process to allow us to develop additional

drugs with a variety of cytokine mixtures to expand our product offerings.

Our product candidate IRX‑2 currently remains under development and has not yet been approved for marketing authorization in any jurisdiction. The ongoing development program

is investigating use of IRX‑2 as an immunotherapeutic neoadjuvant (pre-surgical) and adjuvant (post-operative) treatment for advanced HNSCC and other indications.

The HNSCC development program is being conducted under FDA Investigational New Drug, or IND, #11,137 filed on June 30, 2003 and is ongoing. Potential use of IRX‑2 in other

cancer indications is also being conducted by independent clinical researchers as investigator‑initiated trials.

The HNSCC program has received fast track designation, approved November 7, 2003, and orphan drug designation, conferred on July 7, 2005, from the FDA. We have not submitted a

request for orphan drug designation in the European Union, or EU, though we may seek such designation in the future.

Our findings to date from nonclinical studies of IRX‑2 include murine acute toxicology as well as acute and chronic primate studies. These studies detected circulating

associated cytokines yet were associated with benign toxicological findings. A further murine study demonstrated PD/PDL‑1 synergy when additively administered with IRX‑2.

Clinical studies in humans involving IRX‑2 show immune marker activation in patients treated with IRX‑2. In a prior clinical trial, a correlation was shown between marker

activation and disease-free survival in head and neck cancer.

4

Our clinical pipeline of therapeutic studies focused on oncology indications of high unmet medical need includes:

| • |

Monotherapy studies:

|

| • |

INSPIRE, a Phase 2B study involving 105 patients with HNSCC. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02609386).

|

| • |

BR-101 - A study involving 16 patients with neoadjuvant breast cancer performed at the Providence Portland Medical Center. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02950259).

|

| • |

CIN-201 - An open label single arm Phase 2 trial of the IRX‑2 regimen in women with cervical squamous intraepithelial neoplasia 3 or squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03267680).

|

| • |

Combination studies:

|

| • |

BAS-104 - A basket study originally intended to enroll 100 patients with metastatic bladder, renal, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma, and head and neck cancer being held at the Moffitt Cancer Center, using IRX‑2 in

conjunction with Opdivo (Nivolumab), an immunotherapy cancer treatment marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Details of this trial can be found on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03758781).

|

| • |

HCC-107 - A study involving 28 patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC, being held at HonorHealth Research Institute, City of Hope Medical Center and Texas Oncology at Baylor Charles A. Simmons Cancer Center using IRX‑2 in

conjunction with Opdivo, a cancer treatment marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03655002).

|

| • |

GI-106 - A study involving 20 patients with metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancers (GI) being held at HonorHealth Research Institute, City of Hope Medical Center and Texas Oncology at Baylor Charles A. Simmons Cancer

Center using IRX‑2 in conjunction with Keytruda (Pembrolizumab), an immunotherapy cancer treatment marketed by Merck. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03918499).

|

| • |

MHN-102 - A study involving 15 patients with metastatic head and neck cancer being held at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute and University of Michigan Health System using IRX‑2 in conjunction with Imfinzi

(Durvalumab), a cancer treatment marketed by AstraZeneca plc. Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03381183).

|

| • |

BR-202 - A study involving 30 patients with neoadjuvant triple negative breast cancer, held at the Providence Portland Medical Center using IRX‑2 in conjunction with a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) and chemotherapy treatments.

Details of this trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04373031).

|

Other than the INSPIRE study, each of the studies described above is an investigator-sponsored study for which we are providing IRX‑2 as study drug and financial support to

conduct the trial.

Our goal is twofold: to rapidly advance our IRX‑2 platform to become a leader in immunologic therapy for various types of cancer as both a first-line therapy and in combination with other cancer

treatments, and to commercialize the gene editing technology licensed from the Licensors:

| • |

Pursue commercialization of gene-editing technology. Develop analog mRNA based technology and proprietary delivery system licensed from the Licensors for gene therapy, and cellular engineering in

the treatment of indications of high unmet medical need in oncology and other conditions.

|

5

| • |

Advance combination trials with checkpoint inhibitors. Once INSPIRE trial are released, we plan to use those results as a catalyst in addition to six other clinical trials with multiple data

read-outs anticipated in 2022 and later.

|

| • |

Pursue partnerships to advance our clinical program. We are pursuing partnering opportunities with leading biopharmaceutical companies for the development and commercialization of IRX‑2.

|

| • |

Opportunistically in-license/acquire complementary programs. We may seek additional products to license or acquire in order to expand our product pipeline. This includes products that we may seek

to develop if we exercise our option to exclusively license certain additional technology from the Licensors.

|

| • |

Regulatory Strategy. We believe that our assets may be deemed to be unique and to represent potential breakthroughs in cancer treatment. We will endeavor to seek breakthrough therapy designation

with regulatory agencies for IRX‑2 for one or more indications and for any other product we may acquire or in‑license that could potentially lead to accelerated clinical development timelines. We cannot, however, assure you that we will

receive breakthrough therapy designation for any indications or that any breakthrough therapy designation we do receive will necessarily lead to a faster approval time.

|

| • |

Intellectual Property. We continue to pursue additional intellectual property based on data from IRX clinical studies.

|

IRX‑2 Technology

IRX‑2 is an allogeneic, reproducible, primary, cell-derived biologic with multiple active cytokine components that act on various parts of the immune system to activate the

tumor microenvironment. IRX‑2 contains multiple human cytokines that promote or enhance an immune response. IRX‑2 is administered as a subcutaneous injection in proximity to lymph node beds harboring metastatic cancer.

IRX‑2 is produced under current good manufacturing practices, or cGMP, following stimulation of a specific population of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, or PMBC,

using a specified mitogen. These cells consist of lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, NK cells) and monocytes. Cytokine production induced by the employed mitogen mimics that observed after brisk stimulation of human immune cells by an immunogenic

pathogen or an infection. PBMCs are obtained from FDA-licensed blood banks meeting all criteria for further human use.

Early immunotherapeutic approaches to cancer tended to oversimplify the immune system, often based on the hope that a single target or receptor might restore cellular immune

responses. Today we know that the immune system represents a complex interaction of cells. These include the cells that interact to create immunization, antigen‑presenting cells called dendritic cells, or DCs, and different types of T cells

required for an anticancer immune response. It is now known that defects in these cells exist in cancer and that these defects must be reversed to generate effective cellular immune responses. In addition, because tumors induce immune suppression

through multiple mechanisms, next-generation active immunotherapies must also effectively counteract these mechanisms of tumor-induced immune suppression. For these reasons, we believe the multiple cytokines present in IRX‑2 may be demonstrated to

be particularly effective in reversing the multiple immune deficits in cancer patients.

Preclinical data from animal and in vitro studies, as well as biologic data from patients in clinical trials, demonstrate that IRX‑2 acts in multiple ways to augment the

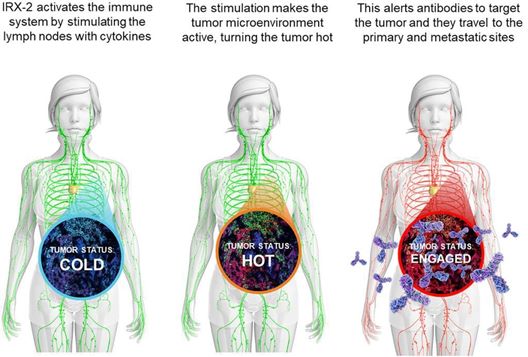

immune response. The following illustration shows how IRX‑2 is believed to use its multiple active cytokine components to enhance the immune response:

6

While the sample size in these studies was not statistically significant, data collected to date suggest that IRX‑2 reduces the immune suppression that is often seen in the

cancer tumor microenvironment held to be associated with reduced immune recognition of solid tumors mediated by surface proteins. This immunomodulatory activity appears to occur through the restoration of immune function and activation of a

coordinated immune response against the tumor. IRX‑2 contains numerous active cytokine components, which is believed to restore and activate multiple immune cell types including T cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells to recognize and

destroy tumors.

These data are derived from the following three studies of IRX‑2:

| • |

The Phase 2a study described below in “Historical Background of the INSPIRE Study,” the results of which were published in December 2011 in the journal Head and Neck. The article reported that

IRX‑2 showed an immunologically mediated antitumor effect, suggested by pronounced lymphocytic infiltration seen in some tumors and by the tumor reductions observed at the end of the 21-day regimen in 11 patients, and by means of a 75%

reduction of glycolytic activity in the tumor and lymph nodes on post-treatment PET scans in one patient.

|

| • |

The BR-101 early stage breast cancer study described below, the results of which were published in April 2020 in the journal Clinical Cancer Research. The article reported that IRX‑2 showed

potentially favorable immunomodulatory changes, supporting further study of IRX‑2 in early-stage breast cancer and other malignancies.

|

| • |

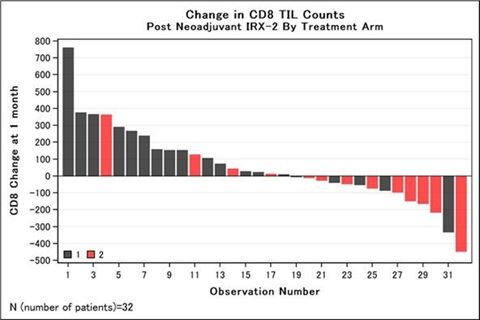

The INSPIRE study described below in “INSPIRE Phase 2B Study Details,” the results of which were published in December 2020 in the journal Oral Oncology. Paired biopsy and resection specimens

from 62 patients were available for creation of tissue microarray, or TMA, and multiplex immunohistology, or IMH, analysis. In this protocol, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte, or TIL, counts by TMA were performed manually under 200x

magnification by a technician blinded to clinical outcome. Additional details of the methodology of TMA and IMH are provided in the publication. Treatment with IRX‑2 was associated with significant increases in CD8+ infiltrates

(p=0.01) compared to the control arm, as shown in the graph below.

|

7

Increases in CD8+ TIL infiltrate scores of at least 10 cells/mm2 were used to characterize immune responders based on prior findings that each 10-cell

increase in CD8 cell density was associated with a significant decrease in multivariable hazard risk of death from study of biopsy specimens obtained from over 200 oral cavity patients treated surgically (Ref 1, 2 below). Immune responders were

more frequent in the IRX arm than the control arm (74% vs 31%, p=0.01), as shown in the table below.

Change in Mean ( ± SEM) Immune Cell Counts1 in Primary Tumor

Before and After Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy with (Regimen 1) or without (Regimen 2) IRX‑2

Before and After Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy with (Regimen 1) or without (Regimen 2) IRX‑2

|

Overall

n= 32 |

Regimen 1

n= 19 |

Regimen 2

n= 13 |

p16+

n=6 |

p16-

n= 26 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mean

|

SEM

|

Mean

|

SEM

|

Mean

|

SEM

|

Mean

|

SEM

|

Mean

|

SEM

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

CD4

|

14.4

|

20.1

|

29.3

|

31.2

|

-7.4

|

19.2

|

-2.6

|

57.1

|

18.3

|

21.5

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

CD8

|

56.8

|

40.7

|

131.3

|

52.8

|

-52.2

|

52.4

|

-75.8

|

61

|

87.3

|

46.4

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

FOXP3

|

37.8

|

43.7

|

59.5

|

42.3

|

6.2

|

89.8

|

-68

|

45.1

|

62.3

|

51.9

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

CD20

|

-8.4

|

29.1

|

-5.3

|

48.6

|

-12.8

|

14.8

|

-111.3

|

128.9

|

15.4

|

20.2

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

CD68

|

24.4

|

19.7

|

-7

|

20.1

|

70.2

|

35.8

|

-21.2

|

27.7

|

34.9

|

23.1

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

TILws2

|

36.2

|

29.5

|

74

|

35.4

|

-19

|

48.6

|

-47.8

|

48

|

55.7

|

33.8

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

1

|

Cell counts are per mm2.

|

|

2

|

TIL weighted score.

|

|

1-

|

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1368-8375(20)30364-X/h0155

|

|

2-

|

[33] Spector ME, Bellile E, Amlani L, Zarins K, Smith J, Brenner JC, Rozek L, Nguyen A, Thomas D, McHugh JB, Taylor JMG, Wolf GT, the University of Michigan Head and Neck SPORE Program5. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic

in HNSCC. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2427. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 31486841.

|

The data from the INSPIRE Phase 2B trial described above are interim data available under the trial protocol in August 2019 (approximately 1.5 years after all patients

received their neoadjuvant regimen and had surgery completed). The primary endpoint of the INSPIRE trial is event-free survival of study subjects who received treatment for their cancer which included IRX‑2, compared to subjects whose treatment for

their cancer did not include IRX‑2. The final trial results on all primary, secondary and exploratory endpoints will be assessed four years after randomization of the last patient (which occurred in February 2018) and is expected to be reported in

the first half of 2022.

8

About Interleukin 2

One of a group of related proteins made by leukocytes (white blood cells) and other cells in the body. IL-2 is made by a type of T lymphocyte. It increases the growth and

activity of other T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes and affects the development of the immune system.

IL‑2 is classified as a “biologic response modifier,” or BRM, or “biologic therapy.” BRMs modify the body’s response to cancer cells. IL-2 is part of a family of proteins

called cytokines. Cytokines act primarily by communicating between the various cells of the body’s immune system.

IL‑2 has essential roles in key functions of the immune system, tolerance and immunity, primarily via its direct effects on T cells. In the thymus, where T cells mature, it

prevents autoimmune diseases by promoting the differentiation of certain immature T cells into regulatory T cells, which suppress other T cells that are otherwise primed to attack normal healthy cells in the body, arguably mitigating off target

effects associated with immune system activation . IL‑2 enhances activation-induced cell death, or AICD. IL‑2 also promotes the differentiation of T cells into effector T cells and into memory T cells when the initial T cell is also stimulated by

an antigen, thus helping the body fight off infections. Together with other polarizing cytokines, IL‑2 stimulates naive CD4+ T cell differentiation into Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes while it impedes differentiation into Th17 and follicular Th

lymphocytes.

IL‑2’s expression and secretion are tightly regulated and function as part of both transient positive and negative feedback loops in mounting and dampening immune responses.

Through its role in the development of T cell immunologic memory, which depends upon the expansion of the number and function of antigen-selected T cell clones, IL‑2 plays a key role in enduring cell-mediated immunity.

Traditional high dose, recombinant IL‑2 therapies have demonstrated severe side effects, including:

| • |

flu-like symptoms (fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, fatigue);

|

| • |

nausea/vomiting;

|

| • |

dry, itchy skin or rash;

|

| • |

weakness or shortness of breath;

|

| • |

diarrhea;

|

| • |

low blood pressure;

|

| • |

drowsiness or confusion; and

|

| • |

loss of appetite.

|

More serious and dangerous side effects sometimes are seen, such as breathing problems, serious infections, seizures, allergic reactions, heart problems, kidney failure or a

variety of other possible complications. The most common adverse effect of high-dose IL‑2 therapy is vascular leak syndrome (VLS; also termed capillary leak syndrome). It is caused by lung endothelial cells expressing high-affinity IL‑2R. These

cells, as a result of IL‑2 binding, causes increased vascular permeability. Thus, intravascular fluid extravasates into organs, predominantly lungs, which leads to life-threatening pulmonary or brain edema. Other drawbacks of traditional

recombinant IL‑2 cancer immunotherapy are its short half-life in circulation and its potential to predominantly expand regulatory T cells at high doses.

Unlike traditional drugs based on IL‑2, IRX‑2 is derived from human blood cells, or hu IL‑2. This difference confers several distinct advantages:

| • |

IRX‑2 has been well tolerated at doses that have been used in clinical trials to date.

|

| • |

IRX‑2 takes advantage of multiple cytokines, while traditional IL‑2 only utilizes a single cytokine.

|

| • |

IRX‑2 is designed to allow for natural folding believed to lead to greater activity, while traditional IL‑2 has shown abnormal folding impacting functionality.

|

| • |

IRX‑2 is administered subcutaneously at physiologic doses, while traditional IL‑2 utilizes high doses which potentially contributes to the severe side effects noted above. Physiologic dosing allows for the

traditional dose to be reduced to levels that allow for the replacement of normal IL‑2 levels in the body.

|

9

The INSPIRE Study

Historical Background of the INSPIRE Study

The IRX‑2 regimen has been studied in patients with HNSCC in two previous open-label, multi-center studies. Also, a phase 1 trial evaluated the IRX‑2 regimen as a therapy for

advanced disease, which reported that the IRX‑2 regimen was well tolerated.

In 2011, results were reported for a Phase 2a trial of IRX‑2. This trial was an open-label study involving 27 patients, 26 of whom completed the study. The primary endpoint of

the study was to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of the immunotherapy regimen including IRX‑2 in the neoadjuvant setting in previously untreated patients with advanced (Stage II to IVa) HNSCC. The primary study objective was to demonstrate

the safety of this immunotherapy regimen based on adverse events (AEs), changes in clinical laboratory measures (hematology, chemistry, and urinalysis), vital signs, and physical examinations. Secondary objectives were clinical, pathologic, and

radiographic tumor response; and patient disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

Most recombinant cytokines, such as IL‑2, are tested in the same manner as traditional oncology drugs, where the maximum tolerated dose is sought. Typical cytokine therapies

in cancer treatment use extremely high doses, in the millions of units per administration. Thus, AEs such as fever, hypotension, malaise, anemia, leukopenia and hepatic and renal dysfunction are commonly reported, and often lead to discontinuation

of the treatment. IV administration of cytokines is frequently associated with an acute phase reaction characterized by rigors, fever, an increase in neutrophils, a decrease in lymphocytes and changes in hormone levels. By contrast, the IRX‑2

regimen, which contains physiologic quantities of cytokines, showed greatly improved tolerability over typical recombinant cytokine therapies.

The results of the Phase 2a study were published in December 2011 in the journal Head and Neck. The article reported that IRX‑2

showed an immunologically mediated antitumor effect, suggested by pronounced lymphocytic infiltration. Lymphocytic infiltration, or LI, was measured by a 100-mm Visual Analog Scale, or VAS, score, in which 100 mm signified lymphocyte infiltration

of the entire primary tumor section and 0 mm signified no lymphocyte infiltration in the tumor specimen. The mean VAS score for all 24 patients was 22.6 mm on the samples obtained at surgery. Patients were grouped into low VAS score (below the

overall mean) and high VAS score (above the overall mean) cohorts. There were 14 patients in the low VAS score cohort with scores between 2 and 21 (median of 9.5), and 10 patients in the high VAS score cohort with scores between 27 and 66 (median

of 37.0). Patients in the high-LI group included fewer oral cavity patients (50% in high LI vs 60% in low LI) but were similar with respect to tumor sites. Seventy percent of high-LI patients were stage IV, whereas only 60% of low LI were stage IV.

The LI score was used to determine whether the degree of LI correlated with survival. Patients with a high-LI score had an improved survival trend compared to those with low LI, and superior to the survival rate for the combined overall group. (See

below.)

10

Interestingly, LI in resected tumor specimens was considered high in 40% of the patients. The 10 patients with a high-LI score showed an improved survival trend in comparison

to the low-LI group (n = 15) and to the entire study population (n = 26). It is difficult to directly compare these subgroups, because there was some imbalance, with a slightly higher percentage of oral cavity patients in the low-LI group. In the

absence of a randomized control, however, it is impossible to directly attribute the LI to the immuno-therapy regimen. In addition, tumor reductions were observed at the end of the 21-day regimen in 11 patients, and a 75% reduction of glycolytic

activity in the tumor and lymph nodes on post-treatment PET scans was observed in one patient.

With regard to the primary endpoint, eight serious adverse events, or SAEs, were reported during treatment and the 30-day post-operative period in 7 patients, including 3

patients with aspiration pneumonia, 1 patient with asthma exacerbation secondary to upper respiratory infection, 1 patient with a post-operative wound infection, 1 patient with a neck abscess, and 1 patient with an episode of alcohol withdrawal.

Only 1 case of aspiration pneumonia was deemed life threatening (grade 4). None of the SAEs was considered related to treatment except for the post-operative wound infection, which was considered possibly related. Other minor (grade 1 or 2) adverse

events included headache (30%), injection-site pain (22%), nausea (22%), constipation (15%), dizziness (15%), fatigue (11%) and myalgia (7%).

After over more than 36 months of follow-up, 11 of the 27 patients enrolled in the Phase 2a study had experienced tumor relapse (n =

1) or death (n = 10). The pattern of first HNSCC relapse included 3 patients with primary site recurrence, 2 with recurrences in the neck, and 2 with distant metastases. Of the 10 patients who died, 6 died

of cancer (1 from a new primary) and 4 died of other causes. The 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year DFS probabilities after surgery were 72%, 64%, and 62%, respectively. Of the 26 patients whose primary tumor was resected surgically, 2 patients died during

the first year and 5 patients died during the second year after surgery. The probability of surviving after surgery was 92% the first year, 73% the second year, and 69% the third year, which was considered to be an encouraging survival rate

compared to historical norms in patients with HNSCC.

A second finding of the study was that some tumors showed some decrease in overall size after the immunotherapy regimen. Overall tumor shrinkage was modest, although in 4

patients, independent, objective imaging documented a greater than 10% decrease in tumor size. This was unexpected and encouraging after only 3 weeks of presurgical neoadjuvant immunotherapy. No patient achieved a true partial response by modified

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, or RECIST, criteria. Increases in tumor measurements were also seen in some patients, but most patients showed negligible change in tumor dimensions. We believe that these findings suggest the safety of

the neoadjuvant regimen, although final decisions on whether a drug product is safe and effective can only be made by the FDA.

The phase 2a trial did not include a randomized control cohort. The manuscript published in Head and Neck in December 2011 stated the

authors’ belief, however, that the safety results and feasibility of this immunotherapy regimen were intriguing enough to warrant further study and appropriate comparison in a randomized trial.

INSPIRE Phase 2B Study Details.

11

The INSPIRE study is intended to further evaluate neoadjuvant therapy with the IRX‑2 regimen in a randomized trial. In addition, the immunotherapy regimen will be enhanced by

adding four adjuvant booster courses of a shorter IRX‑2 regimen during the first post-operative year.

The INSPIRE study is an open label, randomized, multi-center, multi-national Phase 2b clinical trial intended for patients with Stage II, III or IVA untreated SCC of the oral cavity who are

candidates for resection with curative intent. Subjects were randomized 2:1 to either Regimen 1 or Regimen 2 and treated for 21 days prior to surgery and then post-operatively with a booster regimen given every 3 months for 1 year (a total of 4

times.)

| • |

Regimen 1: IRX‑2 Regimen with cyclophosphamide, indomethacin, zinc-containing multivitamins, omeprazole and IRX‑2 as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy.

|

| • |

Regimen 2: Regimen 1 with cyclophosphamide, indomethacin, zinc-containing multivitamins, omeprazole but without IRX‑2 as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy.

|

Treatments were allocated to study subjects using minimization with a stochastic algorithm based on the range method. Minimization will account for the major prognostic

factors for SCC of the oral cavity (T and N stage) and study center to avoid imbalances in treatment allocation within centers.

Postoperatively, subjects first received standard adjuvant radiation or chemoradiation therapy as determined by the investigators per National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, referred to as NCCN guidelines, and then also received Booster Regimen 1 or 2 as determined in the prior randomization.

Subjects will be followed for the Primary, Secondary and Exploratory endpoints. Protocol mandated follow-up will end 4 years after randomization of the last patient.

The Neoadjuvant IRX‑2 Regimen is a 21-day pre-operative regimen of cyclophosphamide on Day 1, indomethacin, zinc-containing multivitamins and omeprazole on Days 1-21, and

subcutaneous IRX‑2 injections in bilateral mastoid insertion regions for 10 days between Days 4 and 21, as shown in the table below:

|

Agent

|

Dose

|

Route of Administration

|

Treatment Days

|

|||

|

Cyclophosphamide

|

300 mg/m2

|

IV

|

1

|

|||

|

IRX‑2

|

230 units daily (Bilateral injections of 115 units)

|

Subcutaneous at or near the mastoid insertion of both sternocleidomastoid muscles

|

Any 10 days between Days 4 and 21

|

|||

|

Indomethacin

|

25 mg TID

|

Oral

|

1-21

|

|||

|

Zinc-Containing Multivitamins

|

1 tablet containing 15-30 mg of zinc

|

Oral

|

1-21

|

|||

|

Omeprazole

|

20 mg

|

Oral

|

1-21

|

12

The Booster IRX‑2 Regimen is given at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (-14 to +28 days) after surgical resection. It is a 10-day post-operative regimen of cyclophosphamide on Day 1,

indomethacin, zinc-containing multivitamins and omeprazole on Days 1-10 and subcutaneous IRX‑2 injections in bilateral deltoid regions for 5 days between Days 4 and 10 as shown in the table below:

|

Agent

|

Dose

|

Route of Administration

|

Treatment Days

|

|||

|

Cyclophosphamide

|

300 mg/m2

|

IV

|

1

|

|||

|

IRX‑2

|

230 units daily (Bilateral injections of 115 units)

|

Subcutaneous into bilateral deltoid regions

|

Every 3 months.

Any 5 days between Days 4 and 10 |

|||

|

Indomethacin

|

25 mg TID

|

Oral

|

Every 3 months.

Days 1-10 |

|||

|

Zinc-Containing Multivitamins

|

1 tablet containing 15-30 mg of zinc

|

Oral

|

Every 3 months.

Days 1-10 |

|||

|

Omeprazole

|

20 mg daily

|

Oral

|

Every 3 months.

Days 1-10 |

Regimen 2, the control arm of the study, is identical, except that subjects will not receive IRX‑2.

The primary objective of the study is to determine if the event-free survival (EFS) of subjects treated with Regimen 1 is longer than for subjects treated with Regimen 2. The

secondary objections of the study are to (i) determine if OS of subjects treated with Regimen 1 is longer than for subjects treated with Regimen 2, (ii) compare the safety of each Regimen, and (iii) compare the feasibility of each booster regimen.

BR-101 – An open label single arm Phase 1 trial of the IRX‑2 Regimen in early-stage breast cancer. Sixteen subjects with stage I-III

early stage-breast cancer (any histology type) indicated for surgical lumpectomy or mastectomy received 10 days of 230 international units, or IUs, IRX‑2 prior to surgery. The objectives of the study were feasibility, safety, and to assess changes

in stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte score. Preoperative locoregional cytokine administration was feasible in 100% (n = 16/16) of subjects and associated with increases in stromal tumor–infiltrating lymphocytes (P < 0.001). Programmed death

ligand 1 (CD274) was upregulated at the RNA (P < 0.01) and protein level by Ventana PD-L1 (SP142) and immunofluorescence, showing statistical significance. Other immunomodulatory effects included upregulation of RNA signatures of T-cell

activation and recruitment and cyclophosphamide-related peripheral T-regulatory cell depletion. The study concluded that IRX‑2 is well tolerated in early-stage breast cancer and, while Phase 1 trials are generally designed only to test safety and

are not powered to assess efficacy, potentially favorable immunomodulatory changes were observed in this trial, supporting further study of IRX‑2 in early-stage breast cancer and other malignancies.

The primary endpoint of this trial was the number of surgeries delayed due to adverse events from the IRX‑2 regimen, and the secondary endpoint was the change in TIL score as

measured by hematoxylin and eosin TIL count, according to Salgado criteria (a criteria for evaluating TIL set forth by Dr. Roberto Salgado published in the February 2015 edition of the journal Annals of Oncology)

from pre-surgical biopsy to resected tumor specimen. Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02950259).

CIN-201 - An open label single arm Phase 2 trial of the IRX‑2 Regimen in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 or squamous

vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3. Ten subjects will be treated in the Cervical Interstitial Neoplasia, or CIN arm, if 2 or fewer responses are observed, enrollment will be stopped. If 3 or more responses are seen enrollment, will continue to 22

subjects. Five subjects will be treated in the Vulvar Interstitial Neoplasia, or VIN arm, if there is no response observed, enrollment will be stopped. If one or more responses are seen, enrollment will continue to 10 subjects. Patients will be

treated with 4 days of 230 IU IRX‑2 for a total of 2 cycles (each cycle is 6 weeks). Objective responses will be assessed at Week 25 to determine the percentage of patients that achieve pathologic Complete Response or Partial Response and Human

Papillomavirus, or HPV, status will be assessed at 3 months post-surgical incision.

13

The primary endpoint of this trial is to compare the proportion of subjects who achieve a pathologic complete response, or CR, or partial response, or PR, in regimen 1 versus

regimen 2 at week 25, based on the resected surgical specimen. The secondary endpoints are (i) the evaluation of the toxicity and feasibility of the administration of IRX‑2 in subjects with confirmed CIN or VIN and (ii) the evaluation of multiple

parameters to assess the activity of the IRX‑2 regimen for the treatment of CIN or VIN, including (a) the occurrence of clinical CRs or PRs at weeks 6, 13 and 25; (b) the frequency of elimination of HPV in cervical or vulvar tissue using a

commercial HPV genotyping assay and viral load determination by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, (c) analysis of the immune infiltrates in the resected surgical specimens, (d) immunophenotypic analysis of peripheral blood

lymphocytes, (e) frequency of serum antibodies to HPV E6, E7, and L1 proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and (f) ribonucleic acid, or RNA, expression profiling of immune-inflammatory markers from post-treatment resected surgical

specimens. Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03267680)

BAS-104 – A Phase 1b open label trial to evaluate the safety, determine recommended Phase 2 dose, and investigate biologic and

clinical activity in recurrent/metastatic lung, renal, bladder, melanoma, and head and neck cancers. Twenty patients were intended to be enrolled into each of the 5 tumor types (for a total of 100 subjects), 10 which were to be naïve to PD1/PDL1

treatment and 10 of which were to have previously received PD1/PDL1 treatment. Patients will be treated with Nivolumab (on label per approved guidelines) in combination with IRX‑2 for a total of 6 cycles (each cycle is 12 weeks and begins with a 21

day cycle of IRX‑2 treatment). The safety phase of the study consisted of 12 patients, of which 6 will be dosed at 230IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 3 weeks for safety assessment before the next cohort of 6 subjects is enrolled and dosed at 460IU of

IRX‑2 and followed for 3 weeks for safety assessment. If no significant safety issues are noted, the remaining subjects in the trial will be dosed at the 460IU dose of IRX‑2. Objective responses are measured by RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST criteria every

six weeks.

The primary endpoint of this trial is the number of participants who experience dose-limiting toxicities through Day 28. The secondary endpoints are (i) the objective response

rate, determined using RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST criteria, and (ii) progression-free survival as defined by RECIST 1.1 to be the time from Day 1 of treatment to the evidence of progression. Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03758781).

This study was closed to enrollment in the second quarter of 2021 due to strategic realignment within BTX and reimbursement issues at the institutional sponsor after enrolling

11 subjects in the trial. The data are currently being collected and biomarker samples are being analyzed for reporting on the subjects treated in the trial.

HCC-107 – A Phase 1b open label trial of IRX‑2 in combination with Nivolumb (on label per approved guidelines) in patients with

advanced hepatocellular cancer. Twenty eight patients will be enrolled into the study. Patients who were previously treated with PD1/PDL1 agents are not excluded from the trial. Patients will be treated with Nivolumb in combination with IRX‑2 for a

total of 18 cycles (each cycle is 1 month). The study is a standard 3+3 design, where three subjects are enrolled and treated at the 230IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 4 weeks for safety assessment before the next cohort of 3 subjects are enrolled and

dosed at 460IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 4 weeks for safety assessment. If no significant safety issues are noted, the remaining subjects in the trial will be dosed at the 460IU dose of IRX‑2. Objective responses are measured by RECIST 1.1 and

iRECIST criteria every 8-12 weeks and progression free survival, progression free survival at 6 months, and overall survival will be assessed.

The primary endpoint of this trial is to determine the safety profile of combination IRX‑2 regimen and Nivolumab in anti-PD1/PDL1 naïve patients who have failed or not

tolerated at least one line of treatment. The secondary endpoints are (i) to evaluate the overall response rate of the IRX‑2 regimen combined with Nivolumab using RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST criteria, (ii) to evaluate the rate of 6-month

progression-free survival in patients treated with combination IRX‑2 regimen and Nivolumab, and (iii) to evaluate median progression-free survival and overall survival. Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov

(NCT03655002).

MHN-102 – A Phase 1b open label trial of IRX‑2 in combination with Durvalumab (on label per approved guidelines) in patients with

incurable HNSCC. Fifteen evaluable patients will be enrolled into the study. Patients who were previously treated with PD1/PDL1 agents are not excluded from the trial; however. given current treatment paradigms. it is anticipated that the majority

of subjects in this trial will have received prior PD1/PDL1 treatment. Patients will be treated with Durvalumab in combination with IRX‑2 for a total of 12 cycles (each cycle is 4 weeks). The safety phase of the study will consist of 12 patients. 6

that will be dosed at 230IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 4 weeks for safety assessment before the next cohort of 6 subjects are enrolled and dosed at 460IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 4 weeks for safety assessment. If no significant safety issues are

noted, the remaining subjects in the trial will be dosed at the 460IU dose of IRX‑2. Biopsies will be collected pre and post treatment to assess changes in immune activity. Objective responses are measured by RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST criteria every

2-3 months and progression free survival and progression free survival at 6 months.

14

The primary endpoint of this trial is to determine the safety profile of combination IRX‑2 regimen and Durvalumab. The secondary endpoints are (i) to evaluate the overall

response rate of the IRX‑2 regimen combined with pembrolizumab using RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST criteria, and (ii) to evaluate initial median progression-free and overall survival in patients treated with combination IRX‑2 regimen and pembrolizumab.

Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03918499).

This study was originally designed to treat 24 subjects in the trial, but was downsized to 15 evaluable subjects due to strategic realignment within BTX and the partner

company.

GI-106 – A Phase 1b/2 open label trial of IRX‑2 in combination with Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced gastric and

gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Twenty six patients will be enrolled into the study. Patients who were previously treated with PD1/PDL1 are excluded from the study. Patients will be treated with Pembrolizumab in combination with IRX‑2 for

a total of 35 cycles (each cycle is 21 days). The study is a standard 3+3 design, where three subjects are enrolled and treated at the 230IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 3 weeks for safety assessment before the next cohort of 3 subjects are enrolled

and dosed at 460IU of IRX‑2 and followed for 3 weeks for safety assessment. If no significant safety issues are noted, the remaining subjects in the trial will be dosed at the 460IU dose of IRX‑2. Objective responses are measured by RECIST 1.1 and

iRECIST criteria every 6-9 weeks and response rate and median progression free survival will be assessed.

The primary endpoint of this trial is to determine the maximum tolerated dose of the combination of the IRX‑2 regimen and Pembrolizumab as outlined in the treatment arm. The

secondary endpoints are (i) objective response to the combination of the IRX‑2 regimen and Pembrolizumab, which will be documented using standard RECIST criteria, (ii) progression-free survival of IRX‑2/ Pembrolizumab treatment participants at six

months post-treatment, as defined by RECIST 1.1 to be the time from Day 1 of treatment to evidence of progression, (iii) median progress free survival of IRX‑2/Pembrolizumab treatment participants, defined as the time from day 1 of treatment to

evidence of progression as defined by RECIST 1.1, and (iv) median overall survival of IRX‑2/Pembrolizumab treatment participants, defined as the length of time from the start of treatment that patients are still alive. Further information about

these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03381183).

BR-202 – A randomized, controlled, Phase 2 trial of induction lRX-2 immunotherapy to promote immunologic priming and enhanced response

to neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. The trial just recently commenced. Thirty patients will be enrolled into the study (15 into the control arm and 15 into the experimental arm). Patients in the control

arm will receive Pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel plus doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide. Patients in the experimental arm will receive the same as the control arm plus lRX-2. The primary endpoint of this trial is to assess the pathological complete

response rate of Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy and Pembrolizumab plus IRX‑2 plus chemotherapy. Secondary endpoints include assessment of rate of response based on residual cancer burden index and to evaluate stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocyte

quantity. Further information about these endpoints is available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04373031).

The status of each of these trials is set forth below.

|

Protocol

|

Status/number of patients

|

Date of commencement

|

Estimated final trial data availability*

|

|||

|

BR-101

|

Complete/ 16

|

Second quarter 2016

|

N/A (completed and published)

|

|||

|

MHN-102

|

Ongoing/16

|

Third quarter 2019

|

Second quarter 2022

|

|||

|

BAS-104

|

Ongoing/11

|

First quarter 2019

|

Fourth quarter 2023

|

|||

|

GI-106

|

Ongoing/9

|

Second quarter 2019

|

Third quarter 2022

|

|||

|

HCC-107

|

Ongoing/8

|

First quarter 2019

|

Fourth quarter 2022

|

|||

|

BR-202

|

Ongoing/5

|

Fourth quarter 2020

|

Second quarter 2024

|

|||

|

CIN-201

|

Ongoing/10

|

First quarter 2018

|

Third quarter 2023

|

* Interim data may be available sooner.

As we are not the sponsors of these trials, we do not have access to a full listing of all reported AEs for each of the trials. However, to date no SAEs have been reported to

us which were determined to be related to IRX‑2.

15

License and Royalty Agreements

IRX‑2

Unless otherwise stated below, each royalty to be paid under these license and royalty agreements is payable until the last patent for IRX‑2 expires and

runs in perpetuity unless earlier terminated pursuant to the terms described below. There are no milestone payments due under any of these agreements.

License Agreement with the University of South Florida Research Association

On June 28, 2000, IRX Therapeutics, a predecessor to Brooklyn LLC, entered into a series of License Agreements, which we refer to collectively and as amended as the USF

License Agreement, with the University of South Florida Research Association, Inc., or the Research Association. Pursuant to the USF License Agreement, the Research Association licensed the exclusive worldwide rights to certain patents on IRX‑2 in

exchange for royalties equal to 7% of the gross product sales of IRX‑2 (as defined in the USF License Agreement). The USF License Agreement was assigned to Brooklyn LLC in connection with the sale of the assets of IRX Therapeutics to Brooklyn LLC

in November 2018. The Research Association has the right to terminate (i) upon Brooklyn LLC’s entering into bankruptcy or insolvency on a voluntary or involuntary basis, (ii) upon the failure to pay royalties due and payable upon thirty days’

notice, or (iii) upon a material breach or default of the Agreement by Brooklyn LLC, unless such breach or default is cured within a thirty day notice period. Brooklyn LLC may terminate the USF License Agreement for any reason upon six months’

notice to the Research Association.

Royalty Agreement with certain former IRX Therapeutics investors

On May 1, 2012, IRX Therapeutics entered into a royalty agreement, which we refer as the IRX Investor Royalty Agreement, with certain investors who participated in a financing

transaction. The IRX Investor Royalty Agreement was assigned to Brooklyn LLC in November 2018 when Brooklyn LLC acquired the assets of IRX Therapeutics. Pursuant to the IRX Investor Royalty Agreement, when Brooklyn LLC becomes obligated to pay

royalties to the Research Association under the USF License Agreement, it will pay an additional royalty of 1% of gross sales to an entity organized by the investors who participated in such financing transaction. There are no termination

provisions in the IRX Investor Royalty Agreement.

Collaborator License Agreement

Effective June 28, 2018, IRX Therapeutics terminated its Research, Development and Option Facilitation Agreement and its Options Agreement with a collaborative partner, which

we refer to as the Collaborator, pursuant to a Termination Agreement. In connection with the Termination Agreement, all of the rights granted to the Collaborator under the Research, Development and Option Facilitation and the Option Agreement were

terminated, and IRX Therapeutics had no obligation to refund any payments received from the Collaborator. The Termination Agreement was assigned to Brooklyn LLC in connection with the sale of the assets of IRX Therapeutics to Brooklyn LLC in

November 2018.

As consideration for entering into the Termination Agreement, the Collaborator will receive a royalty equal to 6% of revenues from the sale of IRX‑2 for the period of time

beginning with the first sale of IRX‑2 through the later of (i) the twelfth anniversary of the first sale of IRX‑2 and (ii) the expiration of the last IRX patent or other exclusivity of IRX‑2, all as more particularly set forth in the Termination

Agreement. Each party under the Termination Agreement may terminate the agreement upon (i) a material breach of the Termination Agreement by the other party that is not cured within sixty days (or thirty days if such breach is due to Brooklyn LLC’s

non-payment of royalties) or (ii) the other party entering into bankruptcy on a voluntary or involuntary basis where such petition is not dismissed, discharged, bonded or stayed within ninety days.

Investor Royalty Agreement

On March 22, 2021, Brooklyn LLC entered into an Amended and Restated Royalty Agreement and Distribution Agreement, or the Royalty Agreement, with Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics

Investors GP LLC, or GP, Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics Investors LP, or LP, and certain beneficial holders of GP and LP. Pursuant to the Royalty Agreement, among other things, we are required to pay compensatory royalties equal to 4% of net revenues

of IRX‑2 on an annual basis, of which 3% is to be paid to certain beneficial holders of LP and 1% is to be paid to certain beneficial holders of GP. The royalty continues in perpetuity. The Royalty Agreement amends and restates a royalty agreement

Brooklyn LLC entered into with GP and LP on November 6, 2018.

16

License Agreements with the Licensor

On April 26, 2021 , Brooklyn LLC entered into an exclusive license agreement, or the License Agreement, with the Licensor to license the Licensor’s IP and mRNA cell

reprogramming and gene editing technology for use in the development of certain cell-based therapies to be evaluated and developed for treating human diseases, including certain types of cancer, sickle cell disease, and beta thalassemia. Through

the License Agreement, Brooklyn LLC acquired an exclusive worldwide license to develop and commercialize certain cell-based therapies to treat cancer and rare blood disorders, including sickle cell disease, based on patented technology and know-how

of Novellus Therapeutics Limited.

The License Agreement provides that Brooklyn LLC is obligated to pay the Licensor a total of $4,000,000 in connection with the execution of the License Agreement, of which

$2,500,000 has been paid and the remaining $1,500,000 is expected to be paid in July 2021. Brooklyn LLC is obligated to pay to the Licensor additional fees of $5,000,000 in October 2021 and $7,000,000 in October 2022.

Under the terms of the License Agreement, Brooklyn LLC is required to use commercially reasonably efforts to achieve certain delineated milestones, including specified

clinical development and regulatory milestones and specified commercialization milestones. In general, upon its achievement of these milestones, Brooklyn LLC will be obligated, in the case of development and regulatory milestones, to make milestone

payments to Licensor in specified amounts and, in the case of commercialization milestones, to specified royalties with respect to product sales, sublicense fees or sales of pediatric review vouchers. In the event Brooklyn LLC fails to timely

achieve certain delineated milestones, the Licensor may have the right to terminate the rights of Brooklyn LLC under provisions of the License Agreement relating to those milestones.

The Licensor is responsible for preparing, filing, prosecuting and maintaining all patent applications and patents under the License Agreement. If, however, the Licensor

determines not to maintain a particular licensed patent or not to prepare, file and prosecute a licensed patent, Brooklyn LLC will have the right, but not the obligation, to assume those responsibilities in the territory at its expense.

Novellus is a pre-clinical development, manufacturing, and technology licensing entity focused on engineered cellular medicines. Novellus has created, developed, and patented

mRNA-based cell reprogramming and gene editing technologies to create engineered cellular medicines. The synthetic mRNA developed by Novellus is non-immunogenic—it is capable of successfully evading the immune system while being recognized by

cellular processes. The synthetic mRNA is then capable of expressing high levels of proteins for cell reprogramming and gene editing. The mRNA may be formulated for injection into target tissues for cellular uptake and therapeutic treatment.

The synthetic mRNA technology may be used to edit gene mutations through mRNA chemistry or expressed gene-editing proteins to treat genetic and rare diseases. It may also be

used to reprogram human non-pluripotent cells and induce human pluripotent stem cells, or IPSCs. The IPSCs may then be differentiated into pure populations of varying therapeutic cell types. The reprogramming technology offers a rapid,

cost-effective and patient specific therapy using the engineered stem cells created from IPSCs.

Novellus has over 45 granted patents throughout the world covering synthetic mRNA, RNA-based gene editing, and RNA-based cell reprogramming, in addition to specific patents

covering methods for treating specific diseases. There are also greater than 50 pending patent applications throughout the world focused on these and other aspects of the technology. The patent coverage includes granted patents and pending patent

applications in the United States, Europe, and Japan along with other major life sciences markets.

There can be no assurance that Brooklyn LLC can successfully develop and commercialize the technology licensed under the License Agreement.

17

Our Patent Portfolio

As of January 15, 2021, we owned or controlled approximately 8 patent families filed in the United States and other major markets worldwide, including 99 granted, 10 pending

and 11 published patent applications, directed to novel compounds, formulations, methods of treatments and platform technologies. Patent protection for IRX‑2 includes:

|

Summary Description of

Patent or Patent Application |

Jurisdiction

|

Earliest Effective Date

of Patent Application |

|||

|

IRX‑2 Modified Manufacturing Process

|

Granted: US (No. 8,470,562), EP (BE, CH, DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, GB, IT, LI, NL, SW), AU, CA, JP, MX, TR

|

US: 4/14/2009

EP: 4/14/2009

|

|||

|

Method of Reversing Immune Suppression of Langerhans Cells

|

Granted: US (Nos. 9,333,238 and 9,931,378), EP (BE, CH, DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, GB, LI, NL), AU, CA

Published: CN, HK

|

US: 6/8/2012 (No. 9,333,238), 4/13/2016 (No. 9,931,378)

EP: 12/8/2010

|

|||

|

Method of Increasing Immunological Effect

|

Granted: US (Nos. 7,993,660 and 8,591,956), EP (BE, CH, DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, GB, IT, LI, NL), AU, CA, JP

Published: HK

|

US: 8/9/2011 (No. 7,993,660), 11/26/2013 (No. 8,591,956)

EP: 11/26/2008

|

|||

|

Vaccine Immunotherapy

|

Granted: US (Nos. 6,162,778, 9,492,517, 9,492,519, 9,539,320 and 9,566,331), EP (BE, CH, DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, GB, IT, LI, NL), AU, CA, HK, JP

|

US: 7/24/2007 (No. 6,162,778), 10/8/2009 (No. 9,492,517), 11/15/2011 (No. 9,539,230), 2/20/2013 (No. 9,566,331), 7/12/2013 (No. 9,492,519)

EP: 5/17/2010

|

|||

|

Vaccine Immunotherapy for Immune Suppressed Patients

|

Granted: US (Patent Nos. 6,977,072, 7,153,499, 8,784,796, 9,789,172 and 9,789,173), CA, JP

|

US: 10/26/2001 (No. 6,977,072), 5/5/2003 (No. 7,153,499), 7/12/2013 (No. 8,784,796), 6/4/2014 (Nos. 9,789,172 and 9,789,173

|

|||

|

Immunotherapy for Immune Suppressed Patients

|

Granted: EP (BE, CH, DE, ES, FR, GB, IT, NL, LI)

|

EP: 3/9/2007

|

|||

|

Composition for the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer

|

Granted: CA

Published: EP, HK

|

||||

|

Uses of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors and/or CTLA-4 Inhibitors with a Biologic Containing Multiple Cytokine Components |

Pending: AU, CA, EP, IL, JP, KR, NZ, PH, SG, US

Published: BR, CN, EA, IN, MX, ZA

|

||||

US – United States of America

EP – European Patent Convention

BE – Belgium

CH – Switzerland

DE – Germany

DK – Denmark

ES – Spain

FI – Finland

GB – Great Britain

IT – Italy

LI – Lichtenstein

NL – Netherlands

SW – Sweden

AU – Australia

BR - Brazil

CA – Canada

CN – Peoples’ Republic of China

EA – Eurasian Patent Organization

HK – Hong Kong

IL – Israel

IN - India

JP – Japan

KR – Republic of Korea (South Korea)

MX – Mexico

PH – Philippines

SG - Singapore

TR – Turkey

ZA – South Africa

18

Patent Families

Descriptions of our patent families with issued patents in the United States or EU are as follows:

| • |

IRX‑2 Modified Manufacturing Process - A method of making a primary cell derived biologic, including the steps of: (a) removing contaminating cells from mononuclear cells (MNCs) by loading leukocytes onto lymphocyte separation medium

(LSM), and washing and centrifuging the medium with an automated cell processing and washing system; (b) storing the MNCs overnight in a closed sterile bag system; (c) stimulating the MNCs with a mitogen and ciprofloxacin in a disposable

cell culture system to produce cytokines; (d) removing the mitogen from the mononuclear cells by filtering; (e) incubating the filtered MNCs in a culture medium; (f) producing a clarified supernatant by filtering the MNCs from the culture

medium; (g) producing a chromatographed supernatant by removing DNA from the clarified supernatant by anion exchange chromatography; and (h) removing viruses from the chromatographed supernatant by filtering with dual 15 nanometer filters

in series, thereby producing a primary cell derived biologic, wherein the primary cell derived biologic comprises IL-1.beta., IL‑2, and IFN-.gamma.

|

| • |

Method of Reversing Immune Suppression of Langerhans Cells - A method of treating human papillomavirus (HPV), by administering a therapeutically effective amount of a primary cell-derived biologic to a patient infected with HPV and

inducing an immune response to HPV. A method of overcoming HPV-induced immune suppression of Langerhans cells (LC), by administering a therapeutically effective amount of a primary cell-derived biologic to a patient infected with HPV and

activating LC. A method of increasing LC migration towards lymph nodes, by administering a therapeutically effective amount of a primary cell-derived biologic to a patient infected with HPV, activating LC, and inducing LC migration towards

lymph nodes. A method of generating immunity against HPV, by administering an effective amount of a primary cell derived biologic to a patient infected with HPV, generating immunity against HPV, and preventing new lesions from developing.

|

| • |

Method of Increasing Immunological Effect - A method of increasing immunological effect in a patient by administering an effective amount of a primary cell derived biologic to the patient, inducing immune production, blocking immune

destruction, and increasing immunological effect in the patient. Methods of treating an immune target, treating a tumor, immune prophylaxis, and preventing tumor escape.

|

| • |

Vaccine Immunotherapy/Composition for the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer – A method providing compositions and methods of immunotherapy to treat cancer or other antigen-producing diseases or lesions. According to one embodiment of

the invention, a composition is provided for eliciting an immune response to at least one antigen in a patient having an antigen-producing disease or lesion, the composition comprising an effective amount of a cytokine mixture, preferably

comprising IL-1, IL‑2, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-.gamma. (gamma) and TNF-. alpha. (alpha). The cytokine mixture acts as an adjuvant with the antigen associated with the antigen-producing disease or lesion to enhance the immune response of the patient

to the antigen. Methods are therefore also provided for eliciting an immune response to at least one antigen in a patient having an antigen-producing disease or lesion utilizing the cytokine mixture of the invention. The compositions and

methods are useful in the treatment of antigen-producing diseases such as cancer, infectious diseases or persistent lesions.

|

| • |

Vaccine Immunotherapy for Immune Suppressed Patients - A method for overcoming mild to moderate immune suppression includes the steps of inducing production of naive T-cells and restoring T-cell immunity. A method of vaccine

immunotherapy includes the steps of inducing production of naive T-cells and exposing the naive T-cells to endogenous or exogenous antigens at an appropriate site. Additionally, a method for unblocking immunization at a regional lymph node

includes the steps of promoting differentiation and maturation of immature dendritic cells at a regional lymph node and allowing presentation of processed peptides by resulting mature dendritic cells, thus, for example, exposing tumor

peptides to T-cells to gain immunization of the T-cells. Further, a method of treating cancer and other persistent lesions includes the steps of administering an effective amount of a natural cytokine mixture as an adjuvant to endogenous or

exogenous administered antigen to the cancer or other persistent lesions.

|

| • |

Immunotherapy for Immune Suppressed Patients – A method providing compositions of a natural cytokine mixture (NCM) for treating a cellular immunodeficiency characterized by T lymphocytopenia, one or more

dendritic cell functional defects such as those associated with lymph node sinus histiocytosis, and/or one or more monocyte functional defects such as those associated with a negative skin test to NCM. The invention includes methods of

treating these cellular immunodeficiences using the NCM of the invention. The compositions and methods are useful in the treatment of diseases associated with cellular immunodeficiencies such as cancer. Also provided are compositions and

methods for reversing tumor-induced immune suppression comprising a chemical inhibitor and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). The invention also provides a diagnostic skin test comprising NCM for predicting treatment outcome in

cancer patients.

|

19

Patent Term and Term Extensions

Individual patents have terms for varying periods depending on the date of filing of the patent application or the date of patent issuance and the legal term of patents in the

countries in which they are obtained. Generally, utility patents issued for applications filed in the United States and the EU are granted a term of 20 years from the earliest effective filing date of a non-provisional patent application. In

addition, in certain instances, a patent term can be extended to recapture a portion of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, or USPTO, delay in issuing the patent as well as a portion of the term effectively lost as a result of the FDA regulatory

review period. However, as to the FDA component, the restoration period cannot be longer than five years and the restoration period cannot extend the patent term beyond 14 years from FDA approval. The duration of foreign patents varies in

accordance with provisions of applicable local law, but typically are also 20 years from the earliest effective filing date. All taxes or annuities for a patent, as required by the USPTO and various foreign jurisdictions, must be timely paid in

order for the patent to remain in force during this period of time.

The actual protection afforded by a patent may vary on a product-by-product basis, from country to country, and can depend upon many factors, including the type of patent, the

scope of its coverage, the availability of regulatory-related extensions, the availability of legal remedies in a particular country and the validity and enforceability of the patent.

Our patents and patent applications may be subject to procedural or legal challenges by others. We may be unable to obtain, maintain and protect the intellectual property

rights necessary to conduct our business, and we may be subject to claims that we infringe or otherwise violate the intellectual property rights of others, which could materially harm our business. For more information, see the section titled “Risk

Factors-Risks Related to Our Intellectual Property.”

Litigation

For purposes of the following descriptions, the “Pre-Merger Company” refers to Brooklyn Inc. while it operated as NTN Buzztime, Inc. prior to the Merger and prior to changing

its name to “Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics, Inc.”